Australia is an increasingly multicultural nation with nearly a quarter of residents (5.5 million) who speak a language other than English at home. Maintaining these community is important due to their vital role in identity, well-being, family cohesion and relationships, developing additional languages. However, previous studies have shown that it is challenging for parents to transmit their minoritised language to their children in a country such as Australia where English is dominant and other languages are marginalised. Moreover, while much of the existing research reveals the importance of parental agency, it centres on mothers’ roles in children’s learning of community languages within a heterosexual family structure, rather than on fathers’ roles. Limited studies such as those by linguist Piotr Romanowski have found the role of fathers is significant, but little is known about other contexts or communities. What then is the role of fathers in a marginalised context and what are the challenges?

This article explores paternal roles in family language policy within three intermarriage families in Australia, where the fathers are migrants from Japan with Japanese as their first language, and the mothers are Australian and native speakers of English. The most recent Census (2021) reveals that 26,890 families living in Australia were born in Japan, and nearly 40 percent of 45,267 Japan-born residents were married to Australian-born partners (30 percent of whom were Japanese men married to Australian women). The substantial number of Japanese-Australian intermarriage families indicate the need to identify how community, schools, and government can support children’s Japanese language development and maintenance.

Language maintenance in intermarriage families

Many migrant parents wish their children to speak their minority home language. However, the language shift from minority language to socially dominant English is common and rapid and thus poses further challenges to successful language maintenance, particularly in a country such as Australia where English is so dominant. Prominent scholar Jim Cummins argues that maintaining a minority language is both cognitively and linguistically crucial for language minority children, and it is important for parents, regardless of gender, to actively support and maintain their community language(s).

One of the crucial factors that contribute to language maintenance is parental decisions relating to what language(s) to use with their children. Parents’ decisions about language choice at home and the motivation of both parents and children to use (or not to use) the minority language, especially through community contact are factors that strongly influence language use in the family including language use with their children. In addition, parents’ gender may play a role—previous studies show that language minority mothers tended to be more successful in transmitting their languages to their children than language minority fathers.

Family language policy in intermarriage families

Family language policy refers to the decisions made within families in relation to the use of language. According to the late Professor of Linguistics Bernard Spolsky, it consists of three elements: language ideology (what the family members believe about their languages and language use), language practice (what they actually do), and language management (how they manage and control their language practice). Families, however, are not independent of society, and studies have shown that family language policy is influenced by not only internal factors (emotion, identity, family culture and traditions, parental impact beliefs, child agency) but also external factors (sociolinguistic, sociocultural, socioeconomic, sociopolitical).

Any decision, or lack thereof, about the choice of language or (languages) to be used will significantly impact the children’s lives and their relationships and situations where parents do not actively employ any strategies in their language use may lead children to become passively bilingual or monolingual.

Research design and participants

This qualitative study (data collected in 2017) examines three intermarriage families in which the fathers are Japanese and the mothers are Australian. Recruiting fathers to participate in studies is an ongoing challenge, especially in marginalised contexts, thus the sample size is small and may not be generalisable. A Phenomenological Case Study was used for this study where observation, interview, and questionnaires were conducted to capture the participants’ perspectives on Japanese language maintenance in the home. Observation was conducted in each home to capture the language interactions among all family members present, utilising a video recorder. The English proficiency of the Japanese parents was assessed by the researcher (Matsui) based on interview and questionnaire data from the participants (Japanese parents). Additionally, the children’s Japanese proficiency was evaluated based on interview data collected from both the children and their parents. All participants live in a large regional city adjacent to a state capital city in Australia. Pseudonyms are used for all participants.

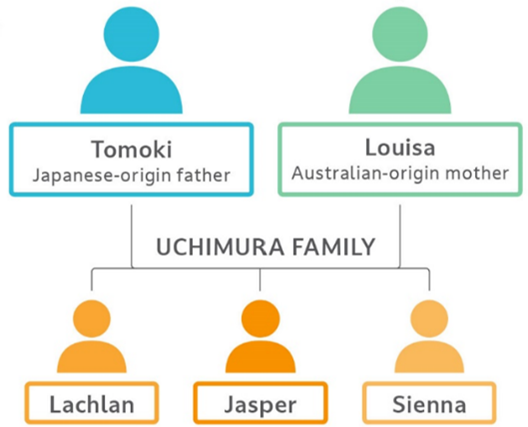

The *Uchimura family

Tomoki was born in the United States to Japanese parents, but his family moved back to Japan when he was 10 months old. His first language is Japanese. He completed high school in Japan and a university degree in Australia. Tomoki met his wife Louisa in Japan while she worked there for 18 months. Tomoki’s English proficiency is adequate for everyday use, but Louisa’s Japanese language skills are very limited. The couple have three children; Lachlan (13 at the time of the study), Jasper (10), and Sienna (7), who were all born in Australia. Tomoki works full-time while Louisa is a stay-at-home mother looking after the household.

Tomoki said that he decided to use Japanese with his children, despite what he felt were Louisa’s concerns that speaking two languages “slows down children’s development”. Louisa expressed some positivity towards speaking Japanese at home, but also said there were some difficulties. English and Japanese coexist in the Uchimura family. Since Louisa cannot speak Japanese, Tomoki and Louisa speak English to each other. Lachlan and Jasper respond to their father mostly in Japanese. If either of them responds using English, Tomoki ignores them until they use Japanese, imposing boundaries around language use expectations and practice. However, Sienna, does not respond to her father if he uses Japanese with her, as she cannot or is unwilling to respond using Japanese. Tomoki believes this is because she spends more time with her mother while he is more involved with the sons through sports and a private Japanese language school. Tomoki felt Sienna, who was three years old at the time, was too young to join the same class as her older brothers, so she never learned Japanese in this context. The three children use English with one another.

The family’s only connection to the Australian Japanese community is that the two sons attended a Japanese language school (Lachlan for two years, Jasper for four years) and that Lachlan chose Japanese as an elective subject in secondary school. Tomoki usually took his sons to the language school, stayed with them during the lesson, and helped out, even though “…she [Louisa] didn’t seem to feel positive about this Japanese lesson. She didn’t oppose it but she didn’t cooperate as much as I wanted her to. She didn’t seem to agree with it.” (Tomoki)

The Uchimura family does not regularly visit Japan. Tomoki feels that spending two weeks in Japan “won’t be fun” for his wife, so he restrains his feelings of wanting to reconnect with Japan and Japanese people.

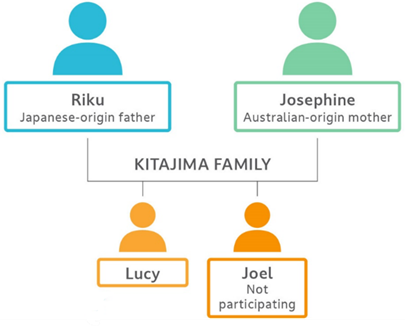

The *Kitajima family

Riku was born in Japan and completed secondary school there. He then went to Canada to study at a cooking school. He can speak English well enough to live and work in daily life. The Kitajima family lived in Fukushima, Japan until 2011, but relocated to Australia to avoid the radioactive fallout from the nuclear power plant disaster. Their daughter, Lucy who was seven at the time of the study was two years old when they arrived in Australia. Riku spends three days a week away from the family home due to work. Josephine does paid work four days a week and spends more time with the children. Josephine lived in Japan for three years and can speak basic Japanese. Lucy attended a private Japanese language school for six months when she was three years old. Since then, she has attended the local Japanese community language school for about four years.

Riku and Josephine both decided to use English in Japan and Japanese in Australia, stating: “I think it is important to speak an opposite language that is spoken outside home.”

Despite their decision, their habit of using English in Japan made the transition difficult after moving to Australia. Riku wants to speak more Japanese with Lucy, but as she grew older the language became more complex leading him to rely more on English because it became difficult for Lucy to understand him.

Josephine has basic Japanese skills, but she struggles to maintain long conversations. Thus, she uses routine Japanese phrases but relies primarily on English. Josephine finds it frustrating when Riku and Lucy speak in Japanese, but she blames herself for not being able to contribute to the Japanese language maintenance.

Riku has a strong desire to maintain Japanese with his children however he understands Josephine’s frustration when she struggles to express herself in Japanese, and he withholds his opinion to keep family harmony. Furthermore, Riku’s absence from home three days a week for work leads to an increased use of English at home. Both Riku and Josephine admit that the use of Japanese at home has decreased over time. They occasionally implement an hour of ‘Japanese-only speaking time,’ but it often ends up being a time when no-one says much.

The Kitajima family has some connections with the local Japanese community in Australia particularly with Japanese families in their neighbourhood. Soon after relocating to Australia, they met the Okuda family, another participant in this study, and became friends. The Kitajima family has visited Japan only once since moving to Australia due to the fear of radioactive exposure in Fukushima. Instead, Riku’s parents have visited Australia several times, reflecting their ongoing close ties even in restricted circumstances.

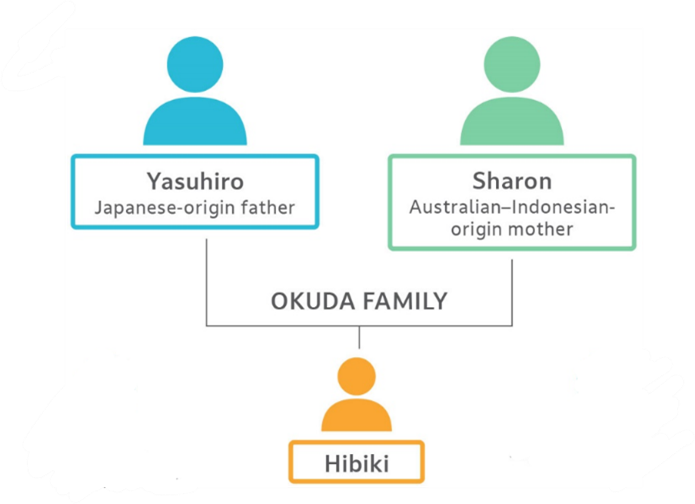

The *Okuda family

Yasuhiro met his wife, Sharon, whose father is of Indonesian heritage, while he was on a working holiday in Australia in 1995. They have a son called Hibiki who was seven years old at the time of the study. Yasuhiro graduated from university in Japan but can speak English well enough to manage daily life. Sharon has a teaching qualification and owns a tutoring centre. She works full-time but spends a lot of time with Hibiki. She has lived in Japan for two years and is a competent speaker of Japanese. Hibiki attended a Japanese language school for six months at the age of two.

Both Yasuhiro and Sharon said that they had not made decisions on language choice. Yasuhiro believes that it would be useful for Hibiki’s future to be able to speak two or more languages and wanted to speak more Japanese with Hibiki, but he says that it is up to his son to decide. Sharon spoke Indonesian at home when young but refused to speak it at school due to bullying for her cultural background and language. This experience shaped her perspective on Hibiki’s Japanese language use.

Yasuhiro usually begins a conversation using Japanese with Hibiki, but Hibiki often ignores him or replies in English leading him to often use English instead. But Hibiki appears to understand the Japanese his father speaks. Yasuhiro and Sharon converse with each other in Japanese. Sharon noted that Yasuhiro’s English had improved since his arrival in Australia but that he’s more comfortable with Japanese. Although she is a fluent speaker of Japanese, Sharon uses English with Hibiki when Yasuhiro is away for work. This suggests that Hibiki is more exposed to English than Japanese at home overall.

In terms of contact with the Japanese community, the Okuda family and the Kitajima family were neighbours and they knew each other well. Hibiki also has some Japanese friends through his parents, although he does not talk to them in Japanese. Hibiki learned Japanese at the same Japanese language school as Lucy Kitajima for six months when he was two years old. He also learns karate, which promotes his connection with Japanese culture. The family also visits family in Japan every two to three years. Yasuhiro stated that “I don’t want him [my son] to forget that he has a Japanese family too.”

Fathers’ roles and challenges

All three Japanese fathers’ commitment to using Japanese played a vital role in transmitting Japanese language skills to their children. This was particularly prominent in the Uchimura family where the mother neither spoke nor understood Japanese. Tomoki’s commitment to using Japanese with his children and providing them with the opportunity to attend the Japanese language school helped foster Lachlan and Jasper’s Japanese language skills. However, Sienna, who did not attend Japanese language school and spent more time speaking English with her Australian mother, struggled to communicate in Japanese, which resulted in her refusal to use it with her father. In the Kitajima family, Riku’s use of Japanese with his daughter Lucy gradually declined and his use of English increased, along with his frequent absences from home. Lucy’s Japanese use also diminished, leading her to rely more on English. Nonetheless, both Riku and Josephine demonstrated their commitment to sending her to Japanese community language schools, providing the opportunity to visit Japan, and welcoming Riku’s parents to Australia—all of which motivated Lucy to use more Japanese. In the Okuda family, Hibiki was not a keen speaker of Japanese, despite his father’ efforts, but he understood some Japanese and Yasuhiro remained committed to connecting him with Japanese culture through his strong interest in Pokémon and karate.

Despite the important role of the fathers in the three families’ language practices and management, they were challenged by many factors, particularly socioeconomic forces since all Japanese fathers worked full-time and did not spend as much time with the children as their mothers. Additional challenges included the children’s limited contact with Japan and Japanese-speaking communities and their often reluctant attitudes to speaking Japanese for various reasons; a lack of clear Family Language Policy or support from a spouse (possibly compounded by indirect Japanese marital communication styles to keep harmony and avoid conflict); and lack of or limited institutional support.

The only father whose children maintained active Japanese use (Tomoki) has overcome such challenges by leading the family with clear and consistent Family Language Policy that was accompanied by institutional support and community contact albeit limited. It is also worth noting that even in this family, the youngest child (who received no institutional support and consequently had less contact with the Japanese community than her siblings) did not develop Japanese literacy or maintain active use of Japanese. This indicates that a Family Language Policy that does not include community language schooling and regular contact with the community as language practice and management is insufficient to maintain the marginalised community language.

To conclude, although most research on Family Language Policy has focused on mothers, our findings suggest that fathers who consistently speak to their children in a minoritised language and support community language schooling also play a key role in language maintenance. While our findings cannot be generalised due to the limited data, our study contributes to the fledging area of research on paternal agency in Family Language Policy and minoritised community language maintenance and highlights the importance of research in this area.

*All names are pseudonyms

Authors: Dr Miyako Matsui and Dr Kaya Oriyama.

Image: Japanese people participating in a parade in Cairns, Australia. Credit: Matthew Kenwrick/Flickr.