The Philippine education system is moving towards mass education at all levels. Basic education transitioned to a 12-year curriculum in 2013 (K-12), introducing two new years of mandatory senior high school. More recently, state higher education was made free for all. As Prospero de Vera, the secretary of the Philippine Commission on Higher Education declared, the Philippines is ‘the only developing country in the world who have tried or implemented free higher education’.

The turn to universalism in education began with kindergarten, that is, pre-primary schooling for five year old children. Since 2012, kindergarten education has been mandatory through publicly funded centres. The 2012 policy change resulted in a significant jump in gross enrolment from 31 percent in 2002 to 98 percent in 2012 (see Table 1). Other countries in the region such as Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam moved also towards universal pre-school education in terms of enrolment before the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is the speed by which enrolment grew in the Philippines that has set it apart from the rest.

School enrollment, pre-primary (kindergarten) (% gross)

Source: World Bank; n.d. means no data available

How did the Philippines universalise pre-school education? Existing studies have examined the reform processes of the K-12 reforms and universal tertiary education, but there is little understanding of the reform process of the universalisation of pre-school education.

Kindergarten universalisation means it is now under the control of the central government

The universalisation of kindergarten means that the education of five-year old children is now officially classified as basic education, while the education of children under five years is classified as early childhood education. This distinction means that what would be considered as welfare (for under five years old) is provided by local governments and basic education (for five years olds and older) is the responsibility of the central government through the Department of Education. The Department is required to ensure 100 percent enrolment of five year old children in basic education.

Folding kindergarten into basic education addresses the institutional fragmentation that previously beleaguered pre-school education. Responsibility for the schooling of children prior to entering basic education suffered from overlapping responsibilities between local and central governments as well as different government agencies. Pre-school education in the Philippines, as in much of the world, used to be dominated by private providers, but reforms have been incrementally introduced to offer a welfare mix that amplified the fragmentation in delivery of pre-school education.

Pre-schools in the Philippines only became possible after World War II because before then children under the age of seven were not legally allowed to be in schools. This created a lack of demand for pre-school education which partly remains today: 10 percent of households in 2017 regarded children of this age as ‘too young to go to school’. While private and civic organisations delivered some preschool education programs, without strong demand the commercial market remained largely underdeveloped. Local governments were historically involved in daycare, but they did not spend enough on it.

National government involvement in the past (such as the Child and Youth Welfare Code signed in 1973 and the Administrative Code in 1971) sought to establish centralised public provision of pre-primary education in every barangay (or village), but these interventions floundered due to lack of resources. The Education Act of 1982, relied on organising classes through parent-teacher associations or teachers’ clubs and other forms of community-financed preschools that accounted for 52 percent of enrollment of children aged three to six years by the 1990s. As a response to the underwhelming investment of local governments on pre-school, in the 1990s central government agencies began to encourage the development of community-financed preschools. The government’s approach was essentially that it ‘could not afford to provide [preschool] service in all divisions…[and subsequently] issued a statement on early childhood education that affirmed the importance of pre-schooling but also stated that preschools should be developed by the community’.

The role of ‘policy coalitions’ in overcoming the institutional fragmentation of pre-school governance

The drastic universalisation of kindergarten was made possible by the presence of a ‘policy coalition’ dedicated to education reforms. ‘Reform coalitions’ fall outside party politics and are collaborative arrangements involving politicians, bureaucratic elites, civil society groups and business groups to forward a reform agenda. Their embeddedness within elite bureaucratic circles and labour intensive advocacy work allow them to achieve almost impossible task of passing the law on taxing alcohol and cigarettes (known as the Sin Tax) in 2012

Scholar Yuske Takagi identified a group of business leaders and ‘ambitious politicians’ as key to education reform during Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo’s presidency in the 2000s. The business advocacy group Philippine Business for Education (PBED) led the coalition by not only expressing private-sector commitment and support to the reforms but also lending expertise and legitimacy through the involvement of an education reform team. Collaboration between other education advocacy groups such as E-NET and Synergeia eventually ‘put education high on the agenda of the presidential candidates for the 2010 elections’. The education reforms that began with universal kindergarten were an outcome of a coalition with deep corporate flavour.

The education policy coalition was particularly impactful in setting the agenda for the kindergarten universalisation during the term of former President Benigno Aquino II. A total of five bills were filed between 2004 and 2010 to introduce mandatory pre-school while at least eight bills were filed between 2010 and 2012, the first two years of the 15th Congress during Aquino’s term. Education reforms featured heavily in Aquino’s campaign agenda but much of it, including a compulsory year of pre-school education can be traced back to the Omnibus Education Reform Act filed in 2008 by Aquino’s running mate, former Senator Manuel Roxas. In the same year, a key figure of PBED, Juan Miguel Luz, released a report which emphasised the need for mandatory pre-school by citing the high correlation between parents’ decisions to put their children into pre-school and the children’s likelihood of finishing primary education. Public expansion became the default policy option, because large companies are less invested in private pre-school than higher education. This is the case because of the absence of institutional protection of private pre-schools in the form of subsidies. The institutional fragmentation where the mixed provision of services worked towards the advantage of quickly reforming the sector.

Is universal kindergarten a sign of change towards a ‘Philippine welfare state’?

The universalisation of kindergarten could be a symptom of broader welfare transitions towards more egalitarian public provision of social services. The broader trend of universalisation of education goes against the colonial legacy of social policies that privilege civil society (and private sector) dominance in its provision. It could also indicate an increasing capacity (and willingness) of the government to achieve radical (and more efficiently targeted) reforms in policy areas traditionally left to the clientelistic whims of the president. The universalisation of kindergarten is also indicative of the ability to push reforms within the Department of Education, notorious for short-term, donor funded reform initiatives at the cost of larger institutional, more political change.

It could also be argued that such expansionist trends in kindergarten education are consistent with welfare state expansion in other developing countries and advanced economies in three ways. First, much of the conventional welfare state literature identifies the role of labour movements and consequently, progressive party politics in the transition towards more universalist welfare provision. The Labour Party in the United Kingdom, for instance, was pivotal in passing universal pre-school.

Second, brisk periods of democratisation have increased the likelihood of changes towards more inclusive policies. This is true in South Korea and Japan where the twin socio-political trends of the end of authoritarianism and demographic change created public demand for welfare expansion. In Taiwan, democratic transition allowed private schools to lobby for expansion of subsidies for preschool education, which in turn improved enrollment rates.

Third, political entrepreneurship can explain why there is turn towards spending more on inclusive education levels like pre-school, away from elitist levels such as higher education. This is particularly the case for Head Start in the USA where Democratic and Republican presidents used its expansion to politically gain from an agenda shift towards addressing poverty.

However, these explanations do not hold ground in the Philippines, which has a ‘stubbornly under-institutionalised’ and elite-led political system, despite being the oldest democracy in Asia. While progressive political personalities have increased representation in both houses of Congress, their ability to implement progressive policies have been significantly constrained. In the absence of agenda-setting institutions based on party lines, politicians need to enter strategic alliances and strike political compromises to be electorally viable, which eventually dilutes their political agenda (as, for example, in the case of national democratic groups like the Makabayan bloc).

The reliance on policy coalition politics suggests a less than durable expansion of welfare, and in fact, suggests a turn away from more participatory means of policymaking. While the policy coalition between bureaucratic elites, civil society workers and business leaders allowed for once-in-a-generation reform like universal kindergarten, the salience of business interest in education would suggest that reforms would inevitably take the form of institutional protection of private schools. In fact, the recent calls for inclusion of private pre-schools into the government’s voucher program (Education Service Contracting) implies a direction towards more institutional protection of private school’s market share.

The universalisation of kindergarten implies that welfare expansion appears to be short-term and ad hoc in the Philippines. Sidel warned that ‘policy coalitions’ run the risk of becoming ‘ensnarled within policy logjams themselves’. These policy coalitions were largely hidden (or isolated) under the administration of recent former President Rodrigo Duterte partly because of the suppression of civil society and the violence against ‘redtagged’ progressive groups and individuals. There are now signs of the unravelling of the layers of reforms instituted in the early 2010s, beginning with the calls to end senior high school as well as the suspension of mother-tongue based learning.

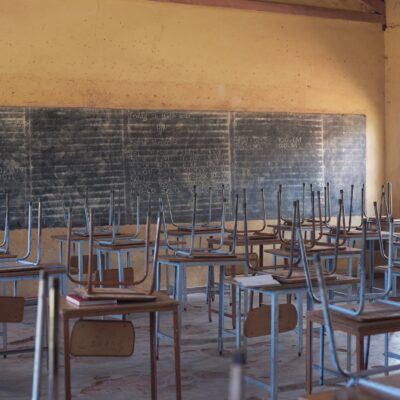

Image: Young children in the Philippines. Credit: Surfing the Nations/Flickr.