Australia’s population continues to grow and is presently more diverse than ever—culturally, religiously and linguistically—with a significant number of Australians originating from Asia. Indeed, the latest Census data shows nearly 30 percent of Australians are born overseas, with almost half of Australia’s resident population having at least one parent born outside the nation. Growing numbers of migrants are coming to Australia from China, India, Vietnam and the Philippines and adding to the ethno-cultural mosaic as well as the social fabric of the country.

Yet, and as the COVD-19 pandemic has shown, the Australian government still lacks a deep understanding of the social, cultural, economic and health conditions of its multicultural communities. If Australia is to meet the social needs of its increasingly diverse population, then all government departments and agencies, as well as social service providers, will need to be well equipped to deliver religiously, culturally and linguistically appropriate services that prioritise the wellbeing and settlement of diverse communities.

This article is based on an Australian Research Council Linkage project that aimed to understand the extent to which, and how well, the social service sector is meeting the needs of our multicultural communities. The current challenges and gaps in equitable and accessible support services systems were identified through preliminary consultations with our partner organisations for this project, the Australian Muslim Women’s Centre for Human Rights, the Victorian Multicultural Commission, and the Ethnic Communities’ Council of Victoria.

The key problem in this area was the emergence of a subtle yet under-investigated shift in government multicultural policy and funding away from community-specific (and multicultural) support to mainstream organisations and service providers. These trends have been observed internationally and reflect deeper ideological shifts towards more conservative politics and macro-economic changes towards neoliberal policies that prioritise efficiencies over welfare.

The multiculturalism backlash in Australia

The ‘multiculturalism backlash’ in Europe and the UK situates Australia’s response to multiculturalism in a broader global context, but our local backlash started gathering momentum before this in the mid-1990s with incoming conservative government led by John Howard. In both contexts, however, this retreat from the multicultural agenda could be attributed to many factors most notably growing levels of ethno-religious diversity; worsening economic outlooks across these societies; and the escalating security situation, particularly in relation to violent extremism.

As European countries began to abandon multiculturalism policies and shift towards neo-assimilationist policies, significant changes to migration and multicultural policies also began to occur in Australia, albeit not to the same extent. This change first manifested with the 1996 Howard government reprioritising immigration policies away from multicultural support of migrants and towards social cohesion and national security. This shift was best documented in the removal of the term ‘multicultural’ from the ministry and also in a gradual shift in funding of settlement and social services away from ethno-specific and multicultural providers towards larger, mainstream agencies.

The term ‘mainstreaming’ began to emerge around this time in reference to the European approach of abandoning ‘target-group-specific policies’ that cater to the needs of specific communities, in preference for an integrative approach in areas such as employment, housing and education. These policy shifts, and other associated changes around multiculturalism, have prompted the critical appraisal of ‘mainstreaming’ both ideologically and also in relation to social service provision to multicultural communities.

Our project on social service provision to multicultural communities

To investigate the impact of mainstreaming policies on service providers catering to multicultural communities, we first wanted to understand the different service provision modes and the diversity of service providers operating in the Cities of Hume and Greater Dandenong, both local government areas in the outer parts of Melbourne, Australia’s second largest city. These local government areas were selected as case study sites in our study design as they are characterised by significant, if slightly different, ethno-linguistic diversity and socio-economic disadvantage. Our rationale was that communities with the most intense and complex requirements would be most in need of social services support. The inclusion of diverse service providers—including those that serve specific ethnic and religious communities, those that cater to various multicultural communities, and those that cater to a general population—was key to understanding the support provided in these cities.

We studied 31 service providers in health, employment and housing, conducting interviews with staff working at these organisations as well as 16 policymakers from local, state and federal governments. Based on the interviews, as well as desk-based research of the service providers’ websites and publications, we discovered there is no binary distinction between ‘ethno-specific’ and ‘mainstream’ providers. Rather, we found that service providers have different degrees of ‘multicultural capacity’, which we conceptualised as: the mission of the service provider to cater to multicultural communities; the inclusion of multicultural personnel within the organisation (leadership and staff); and the level of language support and the depth of cultural competency within the organisation. Importantly, we identified that the funding models of the service providers (that is, how financially secure they were) was key to understanding their impact and function. We conceptualised a service provider’s financial security by looking at their annual turnover and their access to ongoing funding.

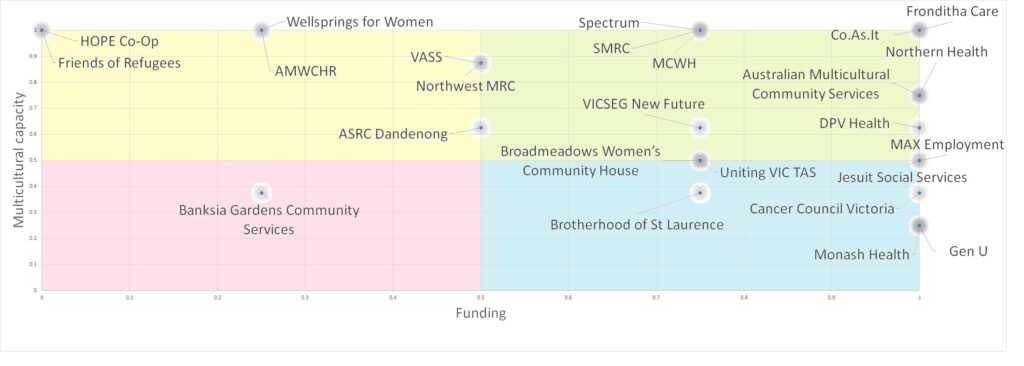

Using a scoring system based on these principles, we attributed a score to each service provider on two axes: its ‘multicultural capacity’ and its ‘funding’ models. Both axes range from 0 (lowest multicultural capacity and most insecure funding model) to 1 (highest multicultural capacity and most secure funding model). This allowed us to map the service providers into four quadrants.

Figure 1 provides a visualisation of a selection of the service providers that we included in our analyses. The service providers in the yellow and pink quadrants are less securely funded, while those in the green and blue quadrants have access to more secure and ongoing sources of funding. Service providers in the yellow and green quadrants have higher multicultural capacity, while those in the pink and blue quadrants are less equipped in their multicultural capacity. This allowed us to identify four types of service providers represented in Figure 1. Those in the yellow quadrant are grassroots/community-specific; those in pink are general community service providers; green are new and established migrant services; and blue are mainstream providers.

Figure 1: Typology of modes of service provision based on their funding security and extent of multicultural capacity

What is the key issue here?

Public and academic discourses about social service provision for diverse communities tend to use a binary approach. Providers are viewed as either mainstream or multicultural services. Mainstream services cater to the whole population (normally including non-English speaking background communities) while multicultural services cater exclusively to migrant communities, in particularly recently arrived groups. In reality, this service provision occurs across a spectrum, with providers often adopting a hybrid model to meet the needs of diverse service users.

There are two main insights to take away from the typology our research revealed. The first is that there are many multicultural service providers with high multicultural capacity that are based on very insecure funding models (yellow quadrant). These are the multicultural service providers that are also key in supporting new, emerging communities, even though they have less secure forms of funding compared to mainstream service providers. This funding insecurity can mean a disruption in the staffing and resources required to ensure a continuity of care for these communities.

The second is that, in the plethora of service provision modes for multicultural communities, the service providers that have high multicultural capacity and are securely funded are primarily aged care and settlement services providers (green quadrant). The needs of the post-war generation of migrants are well-covered through aged care provision. Despite bilingual worker shortages in some of these communities, overall the situation for this demographic cohort is satisfactory with service providers such as Fronditha Care (Greek), Co.As.It (Italian), the Australian Vietnamese Women’s Association (Vietnamese), and the Australian Multicultural Community Services (multicultural aged care) all playing a vital role in ensuring culturally and linguistically sensitive care. Similarly, providers of settlement services, such as Spectrum, Southern Migrant Resource Centre (SMRC) and Settlement Services International, are well financed through federal funding, and have significant bicultural workers to support newly arrived refugees and humanitarian entrants.

Responsive policy and funding are critical

The service provision typology developed in our research shows that while there are particular service provision modes that are well supported and have high multicultural capacity to cater to diverse multicultural communities (such as elderly migrants, refugee and humanitarian entrants’ settlement), a gap remains in the provision of support for new, emerging communities and especially those at the intersection of identities.

Intersectional identities are increasingly complex in multicultural societies such as Australia, and will continue to present serious challenges for service providers in meeting these diverse needs.

In the 1990s, funding cuts made to ethnic welfare organisations triggered public concerns about the welfare of elderly post-war migrants. From 2009, reforms began in healthcare provision in Australia. This included aged care, where policy shifted towards a consumer directed care (CDC) approach. Recommendations were made by the Australian government’s Caring for Older Australians Inquiry report that included a change in funding allocation. Moving from block funding to individualised funding shifted decision-making and agency away from service providers (who used to control the funding allocated to them) to service users.

This CDC approach has also transformed disability support and funding in Australia. The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) was legislated in 2013, and access to this federal funding has placed some multicultural service providers, such as the Victorian Arabic Social Services (VASS), in more financially secure positions to serve their communities.

Yet despite these various initiatives, many multicultural service providers that attend to communities with intersectional needs still bear the highest fiscal burden of care and do so with ever diminishing resources. These service providers (yellow quadrant) cater not only to well-established migrants but also more vulnerable groups such as international students, refugees and migrant women.

The social service sector needs to strengthen its multicultural capacity

Implementing policies and practices that strengthen multicultural capacity across the social service sector is key to serving an increasingly diverse Australian population. Using health services as an example, our research demonstrates strong evidence that health service providers with high multicultural capacity are more effective than mainstream health services in catering to the needs of diverse communities.

Currently, there is no clear policy implementation plan that ensures diversity and inclusion policies are in place. In addition, multicultural communities have long expressed various barriers to accessing services. For example, the final 2013–2015 Access and Equity report produced by the Federal Department of Social Services found that 86 percent of government agencies and departments did not think they were required to meet the minimum whole-of-government standards to ensure that services cater to multicultural communities and as such, ‘only 13 per cent of reporting departments and agencies met this obligation’.

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed the need for greater government support for multicultural communities, and local and state governments in Victoria have responded through the provision of various emergency funding schemes. Yet these short-term measures will create uncertainty in the social service sector once the funds are expended, with questions remaining about the sources of continuous funding for providers to service these communities.

Policy recommendations

We make the following policy recommendations based on our research findings.

- The social service sector will function optimally in a hybrid format that recognises the importance of mainstream and multicultural service providers.

- There needs to be policy in place to encourage resource sharing and collaboration between mainstream and multicultural service providers.

- Local, state and federal government funding bodies responsible for budget allocation for social service provision need to factor in the development of multicultural capacity for mainstream service providers. They also need to devise flexible funding strategies to support new and emerging multicultural communities through specific multicultural service providers.

- A review of diversity and inclusion policies across the social service sector is required. To effectively reduce barriers that service users have long faced, these policies need to consider the inclusion of multicultural leaders and bicultural workers and ensure frequent culturally responsive training is in place for all staff.

- There needs to be a whole-of-government approach for all the above recommendations, at local, state and federal levels.

Why does it matter?

Managing diversity well will be critical for Australia’s post-pandemic social recovery both internally and externally. A commitment to strengthen the support of diverse communities will send a message to the world that Australia has the will and capacity to support all Australians in times of need, from their initial settlement and beyond.

Migration has significant social and economic impact for multicultural Australia. Migrants have a strong desire to contribute to their new country, whether in cities or regional areas. Research shows that migrants and refugees who are well supported in their initial years in Australia are in a much better position to contribute to the country in the longer run, mitigating future social, economic and political risks. A significant proportion of this support will be through social services that assist migrants in their settlement and integration.

As Australia continues to welcome new migrants and refugees, including from Asia, the multicultural capacity of all social services—from initial touch points to settlement and integration—need to be strengthened so all Australians can continue to benefit from our growing diversity.

Authors: Professor Fethi Mansouri, Dr Enqi Weng and Dr Matteo Vergani.

Image: A market in Melbourne. Credit: Alpha/Flickr.