Official policy in Japan towards the Ainu language entails a number of double standards. A policy goal of “raising awareness” of “Ainu culture” has been set as a prerequisite to the establishment of Ainu substantive rights. Yet, Ainu “culture” envisioned under government-controlled standards is an extremely narrow one in which Ainu social issues are disregarded. From a language reclamation perspective, prior research and study of government documents shows that it is not possible to aim for the revitalization and reclamation of Ainu without simultaneously taking into consideration contemporary and historical societal issues.

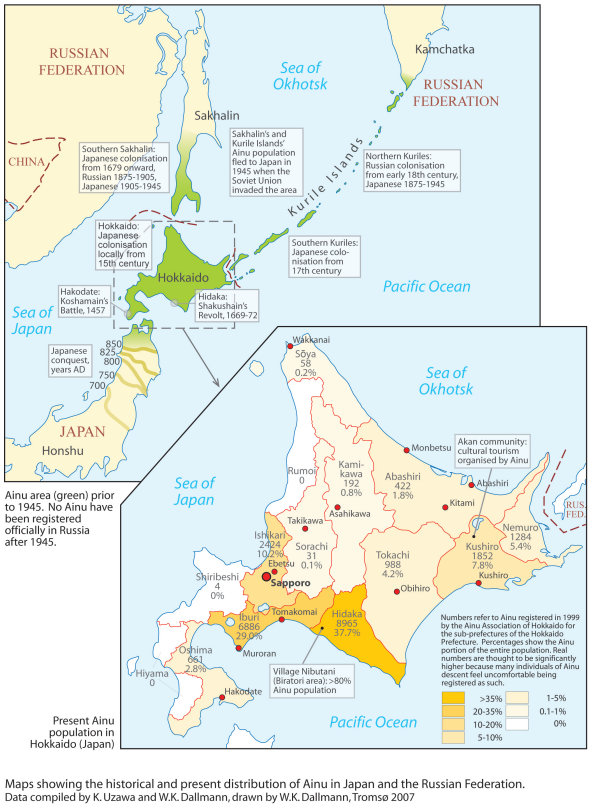

Ainu is the heritage language of the Indigenous Ainu people, who traditionally resided in an area now divided between Japan and Russia. The use and transmission of the Ainu language was heavily disrupted by the assimilationist policies and mass immigration following the colonization of Hokkaido by the Japanese Meiji government in the late 1800s. As of 2009, the Ainu language has been included in the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger as “critically endangered”.

Historian David L. Howell describes the Meiji policy as one of “ethnic negation”, referring to the exclusion of Ainu (or other non-Japanese) identities from the “realm of the politically meaningful”. Despite this, the 1899 Hokkaido Former Natives Protection Act (Hokkaidō kyūdojin hogohō) was the sole Ainu policy in Japan until as late as 1997 (see historian Richard Siddle’s book for discussion of the Act). While Ainu activists, such as the famous Ainu politician Kayano Shigeru, have made efforts to reclaim and revitalize the language since the late 1970s, governmental support continues to be limited, with policy discussions often continuing to center on the need to “raise awareness” of “Ainu culture” amongst the general public.

Obstacles to Ainu language reclamation

Language revitalization is commonly used and understood as a general term that covers all kinds of initiatives aiming for the maintenance and reclamation of languages and their domains of use. However, an increasing number of scholars and language activists now prefer to discuss revitalization as a part of the broader concept of language reclamation, prioritizing decolonization, minoritized epistemologies and social issues instead of focusing mainly on so-called linguistic solutions, such as language teaching and documentation.

In the case of Ainu, multiple non-linguistic challenges have been identified as hindering the contemporary use of the language. A major topic that has emerged in recent sociolinguistic research is the lack of safe spaces to be Ainu, reflecting the situation in which many express hesitation over using or learning Ainu in public, as well as other concerns arising from discrimination. It is apparent, then, that any efforts to increase the number of speakers need to take into consideration the ongoing effects of the history of colonization on language use, including, but not limited to, the lack of prestige and socioeconomic benefit. Also, recognition of the Ainu as an Indigenous people according to recent 2019 legislation inserts an additional element of complication into the picture, as the issue of Indigenous communal rights, including by implication cultural and linguistic ones, has been the focal point of recent litigation by one Ainu community.

Legal context

The 1997 Ainu Cultural Promotion Act (ACPA) and the related establishment of the Foundation for Ainu Culture (FAC, formerly known as the Foundation for Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture) resulted in financial support for Ainu language classes. But Japanese multilingualism specialist John Maher has noted that this was done “without any conception that [Ainu] will or can be used in public education or the media”. Furthermore, the Ainu Cultural Promotion Act did not address “any of the social and political conditions which led to and which continue to provoke the debilitation of the Ainu language”, and it provided an “extremely narrow” definition of Ainu culture. The law also failed to acknowledge the Ainu as an Indigenous people, and the focus on “culture” (as defined by the Act) effectively worked to erase those Ainu who are not involved in such practices. Siddle sees this overt focus on (narrowly defined) “culture” as a way of depoliticization—thus bringing forth concerns which are also central in contemporary discussions on language reclamation as a societal, rather than a purely linguistic campaign.

The more recent Ainu Policy Promotion Act (APPA), passed in 2019 and replacing the 1997 Act, finally granted the Ainu Indigenous status, albeit without Indigenous rights. In other words, it recognizes them as Indigenous by name only, without providing for any substantive rights, such as that to self-determination. The Experts’ Council on Ainu Policy, a Cabinet-level body, composed 90 percent of ethnic Japanese scholars and intellectuals, has previously explained the lack of Indigenous rights as a choice to prioritize a more gradual approach to increase empathy for the eventual establishment of Ainu substantive rights through a policy focusing on “Ainu culture”. Many of the other concerns voiced over the previous ACPA policy also remain unaddressed.

Importantly, it must be noted that the financial subsidies which form the mainstay of policy under the Ainu Policy Promotion Act are under governmental control, with authority to submit applications for these subsidies delegated to municipalities that house Ainu residents, and applications vetted by the Japanese State. Likewise, there is no system in place for how the use of financial gains accruing from the system is to be determined by Ainu residents. While this system has enabled the creation of places of employment that have a strong cultural focus and include the usage of the Ainu language in the workplace, such job sites are limited to municipalities which traditionally have been centers of Ainu tourism.

Gaps, inconsistencies and double standards under Ainu policy

Glaring gaps exist between the:

- legislative demands of the Ainu themselves and the Ainu Policy Promotion Act,

- between the counsel of informed linguists and the content of the APPA; and

- between international standards of Indigenous linguistic and human rights and the content of the APPA.

Ainu demands have consistently framed Ainu language use and promotion as part of a holistic and unified approach that covers Ainu sociopolitical and socioeconomic needs and prioritizes Ainu self-government. The counsel of informed linguists, who testified at hearings of the Expert’s Counsel, [1] likewise calls for increasing the prestige and status of the Ainu language through creation, among other things, of a national Ainu language research institute. But measures under the APPA only provide for Ainu language as one element of the “Ainu culture” to be “promoted”—the wording of the APPA includes the term “Ainu language” once, in relation to defining the components of “Ainu culture”.

Meanwhile, subsidies geared towards Ainu language-learning are administered by disparate entities such as the Foundation for Ainu Culture, the Hokkaido Board of Education, and local municipalities, while Ainu social welfare and education benefits remain the ambit of the Hokkaido Prefectural Government—a siloed and fragmented policy framework which leaves no room for Ainu consolidation or control of their own linguistic or educational futures. This situation is so far removed from that of the original Draft for the New Ainu Law crafted in 1984, and from the Ainu empowerment therein envisioned (Draft), that the law has been referred to as an Ainu law without the Ainu. The APPA has also been criticized from a variety of fronts in the results of a prefecture-wide survey (2022) conducted by a civil society organization.

Furthermore, gaps exist between the officially endorsed approaches for language learning and transmission and the needs pointed out by language activists. While providing language learning opportunities for those individuals with the interest and possibility to participate, the concrete aims of the Ainu language classrooms sponsored by the Foundation for Ainu Culture and Hokkaido Board of Education are unclear in the broader scope of language revitalization and reclamation. Observations from the field suggest a lack of holistic approach, or a lack of long-term commitment to the creation of active speakers within their own communities. In fact, at one point, funding for language-related activities was limited to the teaching of single words appearing in explanations during cultural events. This has left Ainu language activists engaged in such focused alternative approaches as those based on Te Ataarangi (a culturally-affirming language learning method conducted entirely in the Maori language developed out of the Silent Way approach by the Maori to cultivate cadres of speakers in a safe and non-threatening environment) or on parents-and-child study sessions having to rely on their own means of “language learning in circumstances where public assistance cannot be expected”. It goes without saying that those engaged in these serious non-endorsed language revitalization efforts often do so while forced to hold down full time jobs in other economic arenas.

Meanwhile, it cannot be claimed that social conditions in Hokkaido are favorable to Ainu individuals who would outwardly express their Ainu identity by engaging in cultural or linguistic activities. In spite of Article 4 of the APPA prohibiting discrimination against the Ainu, ongoing hate speech geared toward those who would receive financial concessions for engaging in praxis of the Ainu culture continues, including denunciation of the National Ainu Museum. This entails the danger of any practitioner of the Ainu language or culture being singled out as a target of discrimination.

This leads to one of the most significant double-standards of the APPA and the policies on which it is founded: the neglect of colonial history leading to the Ainu’s current marginalized status, and denial of Ainu communal rights.

The Raporo Ainu Nation litigation and the Ainu Policy legislation in light of Indigenous rights reclamation

One point which distinguishes the Ainu from other “indigenous” communities in the world is the lack of landed communities which could constitute a geographical space for speaking the language. Discourses surrounding Indigeneity and language revitalization have changed in the past three decades. A recent example is the litigation by the Raporo Ainu Nation (formerly, Urahoro Ainu Association) against the Hokkaido Government and the Japanese State, calling for the recognition of the Raporo ‘tribe’s’ unextinguished collective right to harvest salmon in the local Urahoro Tokachi River. In addition to the common global Indigenous demand for land and resource rights (often a prerequisite for the maintenance of their cultures), this case also calls into question the legality of the Hokkaido government and Japanese state’s denial of Ainu collective rights. Two issues at stake are the history of colonization of Hokkaido (as well as the Kurile Islands and the southern half of Sakhalin) and the refusal of the Japanese State to recognize any Ainu rights other than those of the individual.

Language use and transmission are often tied with communities. In the case of Ainu, this can be seen in the former presence of Community Language Classrooms in 14 municipalities in Hokkaido, originating from the efforts of Shigeru Kayano who founded a local language school in his home community of Nibutani in the 1980s. If the Raporo Ainu Nation were to succeed in its efforts to get Ainu collective rights to harvest recognized, this could transform related policy and social discourses. This could open the gate to other communal rights such as the right to recognition of educational institutions within the Japanese public school system, and the right to self-determination on how to use Ainu funds for purposes of language transmission and education. These are all vital goals of language reclamation which are being sought elsewhere in the world. But they are not yet achievable in Japan due to the current policy limitations, which are cast into the limelight by the Raporo case. This is a matter which is likely to be a point of contention for at least several years to come. The Raporo Ainu Nation is currently appealing a March, 2024 Sapporo District Court verdict against them that holds that Raporo demands conflict with current Japanese fisheries legislation. The next court hearing is set for the 18th of March, 2025, at the Sapporo High Court.

Conclusions

Policy discussions often center on the need to “raise awareness” of “Ainu culture” as a prerequisite to any changes in Ainu substantive rights. Amidst the narrowly defined culture permitted under such a policy of “idealized awareness”, governmental support for language revitalization and reclamation continues to be limited, and various fronts of Ainu empowerment are being curtailed. Such governmentally driven, constrictive approaches entail a number of double standards, including the sloughing of language into a narrow, governmentally defined version of “culture”, and the recognition of the Indigenous status of the Ainu people without supporting communal rights or addressing the colonial history leading to their current marginalized status.

While the need to spread awareness and cultivate “a sense of pride in self-identifying as Ainu outside of Ainu community’s activities” are meaningful and needed efforts, it is fair to question what kind of awareness is being promoted and whether this should be the main aim of policy. As the notion of language reclamation calls for treatment of minoritized languages as part-and-parcel of larger structural and discoursal inequalities, it is not possible to aim for the revitalization of a language without tackling the broader societal issues that continue to affect language learning and use.

In the Ainu case, failure to ground current government funding for the Ainu in notions of reparation for historical injustice continues to provide the justification for hate speech arguments that these monies are an unfounded concession to Ainu, whether that be as individuals or as a collective. In other words, presented in a de-historicized context as they are, critics see these funds as having no grounding. Ironically, coupled with the lack of support for affirmative action in the media, public K-12 and tertiary education, this leads to a situation wherein in many Ainu minds, “safe spaces” are not achievable in public. A catch-22 ensues in which some feel that, as Ainu, they can only use the language and “be Ainu” in governmentally-designated spaces, or in private.

Whether the Raporo Ainu Nation’s litigation to gain their collective rights to harvest salmon is successful or not, it seems that it would behoove the Japanese State to officially recognize the colonial nature of the annexation of Hokkaido, as well as to simultaneously acknowledge collective elements of language revitalization and reclamation such as socioeconomic standing and status of language and culture. This would go a long way toward changing the “idealized awareness” currently being promoted into a cognizance of the situation as it actually is, which should be the ultimate premise for positive change.

[1] Nakagawa, H. (2009). Ainugo gakushū no mirai ni mukete: kangaekata to annai [Guidelines on how to Think about the future of the Ainu language]. Ainu seisaku no arikata ni kansuru yushikisha kondankai (dai 5 kai) shiryō 2 [Expert Meeting Report on Ainu Policy, fifth meeting, document 2]. Tōkyō: Naikaku.

Authors: Prof. Jeffry Gayman and Saana Santalahti

Image: Wooden Ainu Dolls, emoji mosaic. Credit: Stuart Rankin/Flickr. Map used with the permission of Kanako Uzawa.