The presence of the Korean community in Australia has become much more visible over the past two decades and it is expected to continue to grow based on the continuous influx of people from South Korea in the last 50 years and their offspring to be born in the future. Between 2001 and 2021, the number of people born in South Korea residing in Australia jumped from 38,900 to 102,092; the number of people speaking Korean at home nearly tripled; and the number of people with Korean ancestry grew by an even larger increment.

To the Korean community, the maintenance of Korean language and culture is hugely important. It has been observed that migrants’ languages are better preserved in major cities than in regional or remote Australia and that they tend to be better maintained in States and Territories where they are better represented with higher concentrations of speakers. Korean is no exception. So, what happens to the community/heritage language of Koreans living their dream of a quiet and laid-back lifestyle in beachside and outback towns, away from the major cities?

The term ‘Korean community’ will be used in this article to refer to the group of people who have Korean ethnic and linguistic backgrounds. Those with Korean backgrounds in Australia can be identified easily by combinations of variables such as ancestry (Korean), birth country (North Korea or South Korea) and language spoken at home (Korean) in the national census. Based on the 2021 Australian Census, the Korean community is the 12th largest migrant group when rank-ordered by birth country (South Korea), as well as by languages other than English spoken at home (Korean).

Many migrants continue using the language of their origin after migration. Migrants’ continuous use of the language of their homeland in some domains of their life is called ‘language maintenance’. On the other hand, others abandon their mother tongue and switch to the language of the host country which is referred to ‘language shift’. Research on language shift of migrant groups in Australia has shown that the Korean community maintained its community language (i.e. Korean) well, compared to other ethnolinguistic communities in Australia. Moreover, previous research on parental attitudes towards children’s Korean language maintenance in Korean migrant families in Australia confirmed parents’ strong hope for their children learning and maintaining their heritage language at a high level. (Heritage language is a term used in research communities especially in North America to refer to a language spoken by immigrants and their children which is a societal minority language.) In a relevant study in the Australian context, Korean migrant families appear to use various strategies to help their children learn and retain Korean such as using (only) Korean at home, sending children to community language schools or visiting their home country. However, another relevant study revealed that Korean migrant families struggle with making their children learn and maintain Korean and that exerted effort and support beyond the level of individuals or families is needed.

The Korean community plays a significant role in helping its members to maintain their heritage language. Thousands of businesses run by Koreans, activities of community organisations—including religious institutions such as churches and educational institutions such as community language schools—and interactions between people naturally created through them provide members of the Korean community avenues to use (and learn) Korean. Korean community language schools in Australia—called Hangul Hakkyo among South Koreans and their diasporic populations—provide Korean language and culture education more directly to children of Korean migrant families. Some schools are supported by some Australian State and Territory governments and the South Korean government (through its overseas agencies such as the Korean Education Centre) with the provision of classrooms, wages for teachers and learning materials. However, all Korean community language schools are established by the Korean community’s initiatives; and their administration and teacher supply are solely dependent on the community.

This shows that the community is the source and facilitator of its own community/heritage language maintenance and raises the important question: How do people with Korean backgrounds residing in regional or remote areas in Australia, with no or lack of access to local Korean communities, maintain their community/heritage language?

The Korean community in Australia and its language maintenance

As mentioned earlier, the Korean community is considered to have maintained its community/heritage language well compared to other migrant groups in Australia as it has kept its language shift to English relatively low, especially among the first generation. (Language shift to English is measured by the percentage of people who speak only English at home). Nevertheless, there is a shift rate increase by generation, known as intergenerational language shift. The second generation—of Korean ancestry, born in Australia, with at least one parent born overseas (presumably in South Korea)—shifted to English more frequently than the first generation. In addition, the third generation—of Korean ancestry, born in Australia, with parents both born in Australia—shifted to English even more frequently than the second generation.

The language shift among the Korean community in Australia has shown an interesting trend. In the first generation, women have a higher shift rate than men, in particular, among people older than 24. This has long been ascribed to a higher rate of exogamy (that is, partnering with a person from another ethnolinguistic group) among women born in South Korea than their male counterparts. Understandably, when partnered with someone from another ethnolinguistic group, the person with Korean background will have no choice but to communicate in English or the language of the partner if the partner/spouse does not speak Korean. In addition, the first generation showed much lower language shift rates among church-goers of particular denominations such as Presbyterian or Uniting Church than people affiliated with other Christian denominations or other religions. This is probably because most ‘Korean’ churches in Australia, established, run and attended mainly by people with Korean backgrounds, belong to such denominations. A causal relationship between attending a local Korean church regularly and maintaining the Korean language in the Korean community is difficult to claim. However, it is clear that local Korean churches facilitate the gathering of, and interactions between, members of the Korean community; and they contribute to children’s Korean language learning and maintenance through operating community language schools, as well as through Korean language church services.

The shift rate differentials by gender and religion observed in the Korean community both demonstrate the important role that the availability and accessibility of the use of the Korean language plays in its members’ community/heritage language maintenance. Both trends indicate that the greater the opportunity to communicate in Korean whether at home (e.g. being partnered with a person who can speak Korean) or in the community (e.g. actively participating in social gatherings and activities in the Korean community and interacting with other Korean-speaking people), the more likely people in the Korean community will have opportunities to use the language and consequently maintain it better.

Community/heritage language maintenance of Korean communities in different parts of Australia

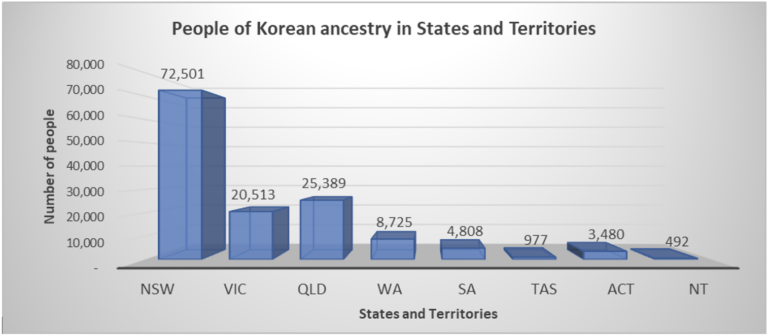

According to the 2021 Census, people with Korean backgrounds in Australia (identified by people of Korean ancestry in the Census) mainly live in its three largest states by population, New South Wales (53 percent), Victoria (15 percent) and Queensland (18.5 percent). More importantly, the majority of people with Korean backgrounds live in Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane (more precisely, the Greater Capital City Statistical Areas as defined by the Australian Bureau of Statistics). Among those with Korean backgrounds in each State and Territory, in New South Wales, 95.5 percent live in Greater Sydney; in Victoria, 95.4 percent live in Greater Melbourne; and in Queensland, 68 percent live in Greater Brisbane. Outside Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane, the vast majority of people with Korean backgrounds also live in their States’ respective capital cities, but the size of the communities is much smaller in those States and Territories.

Image: Reproduction of an old Korean map of Australia and the Pacific. Used with permission from Nicola Fraschini.

The 2021 Census shows that the Korean community in Australia as a whole (with all generations combined) continues to maintain its community/heritage language well and shifted to English only a little—as seen by its language maintenance rate being high (80.8 percent) and its language shift rate being comparatively low (14.6 percent). (The maintenance rate is calculated by the percentage of people speaking Korean at home among those of Korean ancestry.)

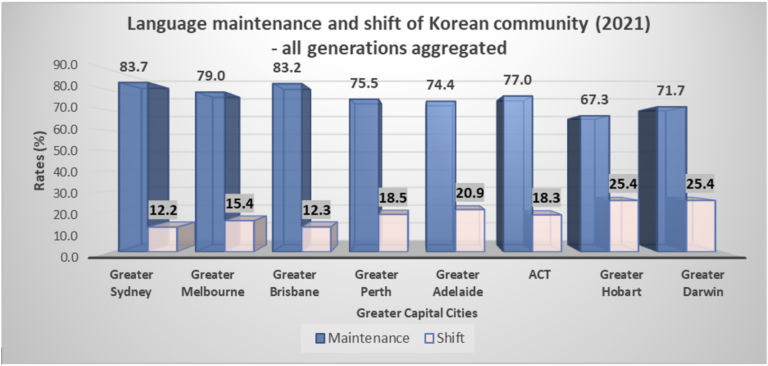

A further analysis of language maintenance and shifts in Greater Capital Cities in different States and Territories reveals an interesting pattern. As the chart below shows, language maintenance rates are generally higher in the three largest states (Sydney, Brisbane and Melbourne) and language shift rates in these cities are lower than those in other capital cities. This suggests that the Korean language is better maintained in cities where a large Korean community is present; and it could be argued that the presence of a large Korean community facilitates its language maintenance.

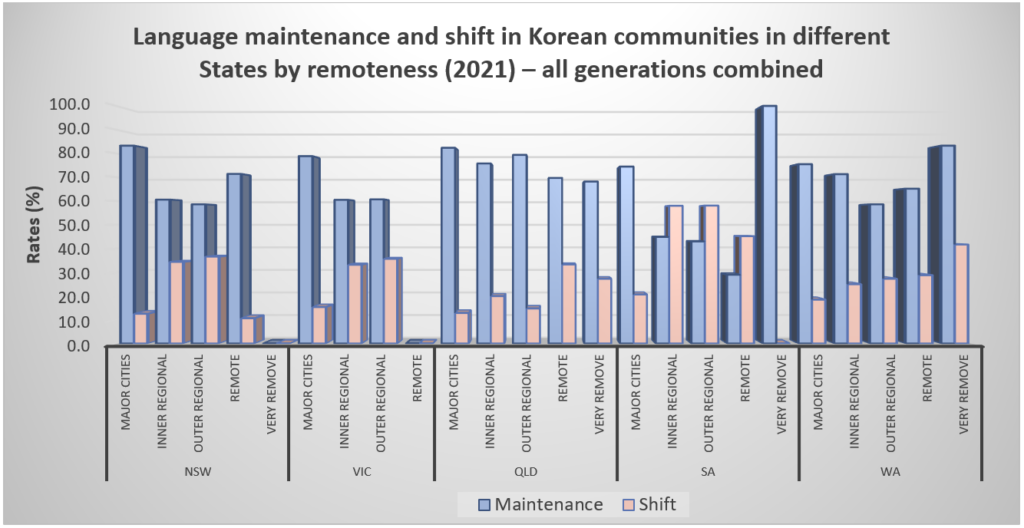

The assumption that community/heritage language maintenance is promoted by the community’s presence or large size (the bigger the better) may be further supported by maintenance and shift rates analysed by remoteness. The Korean community’s language maintenance rate is higher in major cities (81.5 percent) than in regional Australia (66.8 percent in inner regional Australia and 73 percent in outer regional Australia). The rate is again higher in regional Australia than in remote Australia (58.3 precent in remote Australia and 82.3 percent in very remote Australia). The shift rates show the opposite trend: 13.9 percent in major cities; 28.1 percent in inner regional areas; 22 percent in outer regional areas; 31.6 percent in remote areas; and 22.9 percent in very remote areas.

It should be noted that only 5.6 percent of the Korean community in Australia lives in regional or remote Australia and the number of those living in very remote Australia is less than 100 individuals in total. Figures smaller than 20 are not reliable due to ABS’s suppression of small data to prevent identification of individual information, so the difference in language maintenance rates between remote and very remote Australia should be noted with caution.

Although the decreases in the maintenance rate nor the increases in the shift rate occur in a linear way by remoteness, Korean is much better maintained in major cities than in regional Australia, where in turn the language is better retained than in remote Australia. More detailed analyses for language shift and maintenance in Korean communities in different States by remoteness show the same trend, as seen in the chart below.

Challenges of community/heritage language maintenance for people with Korean backgrounds outside major cities

The language maintenance and shift rates of the Korean community in Australia presented above indicate that Korean migrants or their children residing in regional or remote Australia retain their community/heritage language far less well than those living in major cities. This implies that Korean migrants, their children and grandchildren living in regional and remote Australia face much greater challenges to maintain their heritage language. Given the very low number of people with Korean backgrounds in regional or remote Australia (often not enough to be referred to as ‘communities’), it is highly likely that they rarely have opportunities to use Korean outside their homes. If their family members (spouse or children) do not speak Korean, they will have no chance to speak Korean even at home. Like in the movie Minari about the story of a Korean migrant family in a small town in the US in the 1980s, an individual or their family might be the only one(s) speaking Korean. In addition, in regional or remote Australia, ethnic and cultural diversity brought by migrants is usually far less visible than in major cities (although those areas also present a high level of linguistic and cultural diversity with numerous Indigenous communities). This will naturally lead to lack of awareness of the importance (or usefulness) of retaining their heritage language among Korean (or any other) migrants and their descendants.

More importantly, Korean migrant families living in regional or remote Australia, without a sizable Korean community or other people with Korean backgrounds with whom they can interact with, will also have no access to the businesses and community organisations which tend to run community language schools. There are currently 60 Korean community schools across Australia but most of them are in major cities. Moreover, in 2024 71 Australian schools offer the Korean language to their students, but none in Tasmania and the Northern Territory. Improving and increasing accessibility to the facilities that can promote learning and maintenance of Korean, such as the NSW School of Languages or community language schools offered online, seems necessary and urgent. State and Territory governments should make online classes available for more languages. In the case of Victoria, the Victorian School of Languages offers Distance Education for 13 languages, but Korean is not among them. In addition, even the State and Territory governments that currently offer language classes online to students with limited access to language classes (of their choice) in the government school that they attend, provision is confined to the secondary level. For example, online language classes offered by the NSW School of Languages are only for students in Years 9 to 12. Thus, language classes delivered online should also be made available at the primary school level despite practical difficulties and doubts related to the effectiveness of online classes for primary school-aged children.

Additionally, building networks between Korean migrants and their families residing in regional and remote areas will help them to establish a ‘remote/online’ community despite the physical distance between individuals and families as well as building a sense of community and belonging. Most importantly, migrants living outside major cities should be educated about the significance of community/heritage language maintenance through various channels such as campaigns on TV and advertisements on social media. Practical support for language maintenance of migrants living in regional and remote Australia should be provided such as special education for parents, especially those with young children, on how best to support heritage language learning of their children. Where/if online language classes for children of migrant families in regional and remote areas are not available, online resources (such as Languages Online provided by the Victorian government for students’ self-study) should be developed for migrant parents to support them to teach their heritage language to their children at home.

Lastly, the language maintenance and shift of the Korean communities in different parts of Australia presented here suggest that more research should explore language maintenance of migrants living in regional and remote areas. It may seem that the overall picture of Korean communities’ language maintenance presented above reinforces the urban-rural dichotomisation that presents urban areas as diversity-welcoming and dynamic places that foster language maintenance, and rural areas as disconnected and static places that are not ideal for language maintenance for migrants. However, initiatives and efforts of individuals or small communities of migrants in rural areas (which are yet to be discovered), as well as contacts and interactions between migrant and Indigenous communities in those areas should not be understated. Instead, language educators and researchers should not only focus on urban areas for migrant languages and rural areas for Indigenous languages but should also investigate migrant language use in regional and remote areas.

Image: Reproduction of an old Korean map of Australia and the Pacific. Used with permission of Dr Nicola Fraschini.