The modern history of the Kurdish language or languages (we use these terms interchangeably) is one of discrimination and precarity, but also resilience and resistance. Even though there are an estimated 30-40 million Kurds they are stateless, mainly living within Iran, Iraq, Syria and Türkiye where their language/s are suppressed.

In this article we draw attention to Kurdish revitalization efforts and to what we call – inspired by Judith Butler, the feminist philosopher – the Kurdish language right of appearance and visibility.

Historical and political background of Kurdish languages

For centuries Kurdish was overshadowed by the main languages of the Ottoman and Persian empires: Arabic, Persian and Turkish. Nevertheless, Kurdish developed on the margins. Its golden periods unsurprisingly coincided with the rise in power of the Kurdish semi-autonomous emirates located on the border of both empires. Under the patronage of the Kurdish principalities, the Kurdish language varieties of Kurmanji, Gorani, and Sorani flourished and developed into literary languages, although not following a homogenous pattern of development.

During the twentieth century, the redrawing of the national borders and the creation of new states in the Middle East left Kurds stateless and their language and identity ‘minoritised’. As Michael Cronin, scholar of translation studies, aptly remarks minority status is the “expression of a relation not an essence” and is determined by political, economic and cultural forces. The minority status of Kurdish was intensified following hostile policies of the newly established states which implemented a ‘one nation, one language’ vision in their nation-building projects. The Kurdish language, consequently, faced assimilation policies and even linguicide.

In Türkiye, the mere designation of “Kurd” was considered to be a threat to territorial integrity and the Kurdish language was banned from public use. It was only in the 1990s that the use of ‘non-Turkish’ languages became legalised. In Syria the Arabisation policy implemented from 1960 led to restrictions on Kurdish language and culture. Also, in Iraq the Arabisation took the shape of linguicide in the era of Saddam Hussein’s regime (1979–1991). In Iran, Kurds have been deprived of political and cultural rights by different regimes. Although there are provisions for teaching minority languages in the Iranian Constitution, the imprisonment of language teachers and activists is well documented and reminds us of the ongoing challenges.

Recognition of the Kurdish language is closely tied to political recognition of the rights of Kurdish people as evidenced by the official status achieved by Kurdish in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) since 1992 and in the Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (DAANES) since 2014. Only these two Kurdish regions have been able to establish a public system of education in Kurdish. In Türkiye and Iran, Kurdish is only rarely a language of instruction. It is mainly taught as private courses and although an elective class was introduced in Turkish public schools in 2012, it was never implemented on a widespread basis.

Literary and cultural activism

Writing and publishing in Kurdish for much of the twentieth century was an act of resistance and the decision to write or not write in Kurdish is a decision that has occupied modern Kurdish writers. At the very beginning of modern Kurdish literature many writers such as Yaşar Kemal (1923-2015) in Türkiye or Selim Berakat (born 1951) in Syria took up writing in the official languages Turkish and Arabic respectively. Access to publication and better chances for recognition were among the reasons for writing in official languages. The first Kurdish short story was published in 1913 and the first novel in 1935, but the development of Kurdish language literature took place a few decades later and owed a lot to the efforts of Kurdish European diaspora.

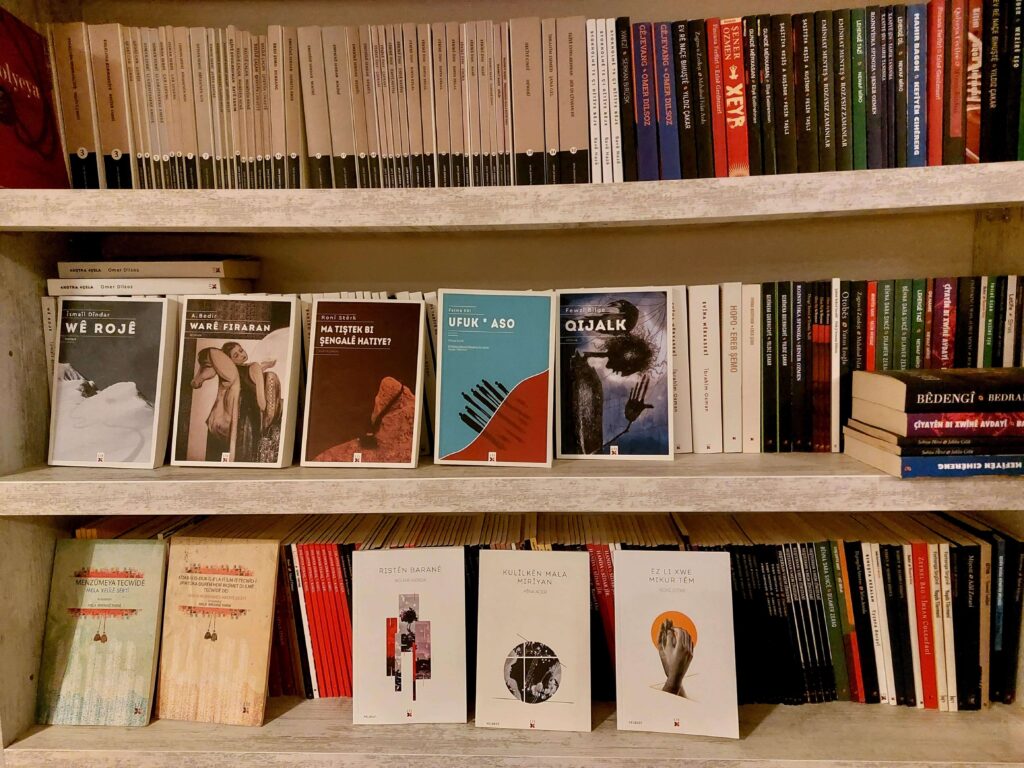

Wêjegeh Amed – The Kurdish bookstore in Diyarbakir (Turkish Kurdistan) presenting new titles by Kurdish authors, 2021. Credit: Dr Joanna Bocheńska.

Writing in Kurdish has become more popular among Kurdish authors even though their efforts are still limited by low readership. Some are motivated to continue with their work to foster change, such as Mehmet Uzun (1952-2007) a renowned Kurdish writer from Türkiye. Uzun came up with the concept of a condensed language, rooted in the tradition of Kurdish proverbs and developed by people living in fear who learn the art of speaking only a little. He invited Kurds to use their mother tongue as a modern tool of communication.

Kurdish language initiatives have grown in popularity over the last two decades. Kurdish languages have been used in music, theatre, TV and cinema including broadcasting for children such as Zarok TV, and have become important strategies for all those who care for their mother tongue and the culture transmitted through it. One of the strategies for Kurdish revitalization relies on collecting, archiving and studying folklore, which is believed to be a rich source of vocabulary and of the language use. Recently the interest in folklore has become popular among the Kurdish youth who not only want to preserve their language but also desire to learn it in the best possible way. The collected vocabulary has since been reapplied in modern contexts such as scientific terminology, cultural magazines and literature. Additionally, Kurdish languages and their folklore are appreciated as a source of indigenous knowledge about nature and the surrounding world.

Translation as a means of revitalization

Translation has been taken up as a means to revitalize minority languages and a way to make its literature accessible. Growing initiatives to translate Kurdish literature into official state languages have given Kurdish language some visibility and recognition within dominant literary spheres of the nations in which they live and can increase the sense of confidence among Kurdish speakers. A case in point is the popularity of Persian translations of Kurdish novels and poetry in Iran. For instance, the Persian translation of Bachtyar Ali’s novel, Axirîn Henarî Dunya (The Last Pomegranate of the World), has been reprinted 14 times.

However, it can also be seen as an act of subordination to the dominant languages. In Türkiye, the practice has raised concerns closely connected to the notorious “Turkification” and assimilation policy of the Turkish Republic, as some Turkish translations of Kurdish novels were published after the Kurdish versions of the novels which reduced readership of the Kurdish version. As many Kurds neither speak nor read Kurdish, having the Turkish translation of Mehmed Uzun’s novel, for instance, almost immediately after the Kurdish original, discouraged them from reaching to the original.

Another important initiative to enrich Kurdish through translation has been the translation of world literature into Kurdish which is cherished by many Kurdish publishers in the Middle East and Europe. Furthermore, translating between Kurdish languages or even transcribing between the Arabic, Latin and Cyrylic Kurdish alphabets (scripts that Kurdish is written in) has helped enable mutual intelligibility among speakers divided geographically.

Translation of Kurdish literature into European languages has also seen slow yet steady progress through the efforts of dedicated individuals and constitutes a form of activism. Kurdish literature such as Sherko Bekes’ Butterfly Valley (2018) and Abdulla Pashew’s Dictionary of Midnight (2019) are bilingual Kurdish-English publications, which encourage the visibility of Kurdish and should be encouraged as a practice for minority languages. Translation can become as Marta García González, scholar of translation studies, argues a “mechanism to promote the language itself” and a “tool in the process of language preservation”.

For Kurdish, the continued suppression of the language, the lack of state and institutional funding and professionalization of translation are the main challenges. Systematic and large-scale translation training has been implemented in the case of Irish, Catalan, and Basque which can be inspiring for the Kurdish language and could be encouraged by organizations such as PEN International.

Broadcasting and new digital spaces

Kurdish speakers embraced technology relatively early with the first radio broadcast by Radio Yerevan organized in 1955 and based in Yerevan, Armenia and in Radio Baghdad (1939–2003). The dominance of the state-controlled television broadcasting was challenged when the first Kurdish satellite television channel, MED TV based in the UK and Belgium, was launched in 1995. It marked the beginning of a new era for developing Kurdish language, culture, and identity. The channel allowed Kurds, divided by international borders, to achieve, in the words of Kurdish scholar Amir Hassanpour, “sovereignty in the sky”. Tens of Kurdish channels (there are no clear statistics, partly due to the uncertain nature of their existence) have since been founded whose main language is Kurdish, which have helped increase the contemporary credibility and legitimacy of Kurdish. The channels have also fostered mutual intelligibility among the speakers of different Kurdish varieties by providing programmes in different languages. The growth of such channels has induced state media in Iran and Türkiye to offer programmes in Kurdish and even set up Kurdish language channels such as the TRT6 in Türkiye broadcasting in Kurmanji and Zazaki. Additionally, over the last two decades the Kurdish TV channels based in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) followed a policy of encouraging the passive knowledge of a second Kurdish language. For example, the news is often read by two speakers (Badini and Sorani) and reportage shot in one language are provided with subtitles in the other.

Other contemporary communications technology also plays a crucial role in language revitalization by providing opportunities for enhancing language development, preservation and dissemination. For example, language applications have been instrumental in the process of learning Kurdish. The crucial aspect of Internet language teaching is its multimedia character even though any technology must follow learning needs. Communications technologies also make available conditions for immersion-based teaching especially for people who find it difficult to access in-person language courses and native speakers to interact with, such as YouTube channels KurdiOnline and Dersa Kurdî. The latter offers simple and entertaining short films with repetitive sections and brief grammar explanations that serve well to develop language skills by both Kurds and foreigners. Social media have also enabled digital language activism, for example Facebook profiles Kurdish Language and Linguistic or Zimanê Kurdî.

Academic activism: Kurdish in the international arena

In the field of Kurdish Studies, communications technology has provided opportunities to develop networks such as Kurdish Studies Network/KSN; Kurdish Gender Studies Network/KGSN, multilingual academic websites for research projects such as kurdishstudies.pl and digital archives such as Digital Archives of the Middle East project in which Kurdish has a prominent position and contributes to making the language visible in the global academic space. The COVID-19 pandemic further revealed the potential of the Internet in many new fields including in the Kurdish Studies networks and it offered the easier possibility to bring Kurdish into focus.

The Kurdish language is rarely welcomed as the language of communication even during the Kurdish Studies conferences organized at European or American universities. Rare exceptions have been a conference in 2016 organised by Jagiellonian University (Kraków, Poland) and by Goethe University along with the International Institute for the Study of Kurdish Societies (IISKS) and Soran University in Frankfurt in 2017. The two Kurdish dialects Kurmanji and Sorani were introduced as the language of abstracts with the advent of the journal of Kurdish Studies (currently Kurdish Studies Journal published by Brill) in 2013. From 2019 onward it has also encompassed the Zazaki dialect.

We believe that introducing Kurdish into the international academic space of Kurdish Studies and familiarizing scholars with its presence and use is important. Kurdish language publications are cited extremely rarely in the international academic space of KS, ignoring the vibrant intellectual field developing in Kurdish homelands. Western-based scholars and their methodological perspectives still dominate the field. During the pandemic we organized a series of online seminars and workshops related to a research project on the revitalization of Kurdish to which we invited Kurdish academics, writers, artists, and activists to present their work in Kurdish. For most of the Kurdish panelists it was the first time they were offered a space to present their research by academic institutions in the global north which points out systemic marginalizations in academia. We followed the same practice at the Kurdish Folklore conference organized by Exeter and Jagiellonian universities in Kraków in 2022. We continued our efforts by organizing online seminars through the Kurdish Gender Studies Network, facilitating conversations with Kurdish women writers who write primarily in Kurdish. The above-mentioned events brought together scholars from Kurdistan, Europe, US and Canada, defying epistemic erasures and linguistic marginalization of Kurdish. Primarily, however, it enabled the Kurdish language to “claim the right to appear” in the international academic space of Kurdish Studies.

In our overview of Kurdish language activism, we have drawn attention to the diverse initiatives encompassing the Kurdish languages: Kurmanji, Sorani, Gorani, Badini and Zazaki. The examples highlighted in this piece attest to the resilience and creativity of the Kurdish speakers who are not at all reconciled with the loss of their languages and struggle to challenge assimilation. It is through claiming the new spaces to highlight the Kurdish language’s existence, knowledge and usage that new opportunities for the Kurdish future become visible.

Authors: Dr Farangis Ghaderi and Dr Joanna Bocheńska.

Main image: Raja, the private school of Kurdish language in Sine (Sanandaj), Iranian Kurdistan, 2022. Credit: Joanna Bocheńska.