In Indonesia and globally, the COVID-19 pandemic has reversed some of the gains made from the collective struggle to close the gender gap. For instance in 2021, reversals in gender parity were apparent, especially in women’s economic opportunities and political empowerment, increasing the time needed to close the global gender gap by a generation from 99.5 to 135.6 years.

To tackle gender inequality, in Indonesia and the wider Asia-Pacific, civil society organisations (CSOs) bear much of the difficult on-the-ground work, supporting women across sectors from health to employment. In the work to address inequality, agencies and scholars distinguish between gender equality and equity. Equity incorporates an understanding that each person has different circumstances requiring different resources and opportunities to reach gender-equal outcomes. The inroads made by women’s CSOs in improving the policy environment and the influence and wellbeing of Indonesian women have been disrupted by the pandemic, with increased political and religious conservatism also posing a threat to earlier hard-won advances.

Below we explore how women in villages in rural Indonesia have responded to the pandemic and the work of CSOs in supporting them, drawing on the work of just some of our partner organisations—PEKKA (Female-Headed Families Empowerment Foundation, which works to politically, socially and economically empower female-headed households), BITRA (the Indonesian Foundation for Rural Capacity Building), which organises and supports grassroots collective action as well as policy advocacy on labour issues), and Migrant CARE, which advocates and supports the establishment of village-based services for migrant workers.

Drawing on survey data and qualitative interviews from late-2020 with women in villages we first visited and studied prior to the pandemic, these findings demonstrate the importance of understanding changes over time and how working towards gender equity is not a neatly upward trajectory, but rather a complicated path with backsliding, ruptures, and uneven advancements. Such findings prompt larger questions about how to achieve durable structural changes to produce gender equity.

Experiences of disruption in villages

The wider economic disruptions caused by the pandemic impacted villages in uneven ways. In late 2020, our University of Melbourne and University of Gadjah Mada collaborative research team surveyed 600 women and men in six villages throughout the Indonesian archipelago on the islands of Java, Sumatra, Sulawesi, and Lombok, and the province of West Timor. Each of these villages have different livelihood options. Some villages have economies that are highly reliant on agriculture, while others are more reliant on tourism, markets, or factories. Across these contexts, the survey found similar pandemic impacts were reported by men and women, with 87 percent of men and 79 percent of women reporting reduced income; although more men reported loss of employment (29 percent) than women (16 percent).

Throughout these six villages, 78 percent of respondents perceived a worsening economy in their local area, but only approximately 40 percent reported this in isolated, predominantly agricultural economies. These contextual differences also shaped how individuals responded to economic hardship created by the pandemic.

Table 1 shows how in the three more rural villages with economies dominated by agriculture, respondents reported borrowing money as their primary coping strategy to deal with the impacts of the pandemic (52 percent, 65 percent, 44 percent). In the other three villages located closer to urban centres, which are characterised by their reliance on markets, factories, and migrant work for employment, only 11-14 percent of survey respondents reported borrowing money.

Table 1. Coping Strategies for pandemic impacts (N=477)

These survey results also show that the most common form of coping strategy across the six village contexts was seeking new sources of income. This was commonly reported across both the peri-urban village near factories (71 percent), market village (65 percent), village with a significant proportion of migrant workers and a tourist economy (65 percent), and a remote village in far-eastern Indonesia with an agricultural economy (67 percent). The widespread popularity of this strategy signals the importance of skills, knowledge, and networks developed prior to the pandemic, including in women’s groups supported by CSOs, for opening alternative livelihood options in times of hardship.

Women’s influence on government responses to COVID-19

The Government of Indonesia has initiated a number of innovative responses to the COVID-19 crisis across several sectors, including health, industry support, social safety nets (e.g. basic food assistance and cash assistance) and economic recovery programs. Of most interest to our research on women’s participation and influence on COVID-19 responses at the village level, is the use of the Village Fund (Dana Desa). The Village Fund was introduced as part of the 2014 Village Law which explicitly emphasises community decision making, poverty reduction and gender equity, creating a framework to improve gender inclusion. In April 2020, the Minister of Villages, Development of Disadvantaged Regions, and Transmigration specifically allowed for villages to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic using the Village Fund through Regulation No. 6/2020 (enacted on 13 April 2020). Under the regulation, the Village Fund could be used for a wide range of COVID-19 response activities, such as the maintenance of neighbourhood facilities, including rehabilitation facilities to isolate COVID-19 victims, personal protective equipment, neighbourhood cleaning and other activities to prevent the spread of the virus, including provision of information and training.

The regulation also allowed for the Village Fund to be used for direct cash transfers (BLT-Dana Desa) for those losing their livelihoods, those unable to access other social protection programs, and those with family members suffering from chronic illnesses. To be eligible, recipients have to be verified by three people that they are indeed poor and have not been included in other programs. Decisions on village responses under the Law are within the authority of the Village Government and decided through village consultative forums.

Significantly, the regulation also provided scope for the establishment of COVID-19 Village Volunteer Teams, known as village COVID-19 Taskforces, headed by the Village Head and including members of various village organisations, local public figures and authorities. These Taskforces were central to decisions on who received cash transfers. Across the villages studied, there were far more men than women on village COVID-19 Taskforces. The 2020 regulation did not specify requirements for general women’s participation in these taskforces. The team structure could potentially have included women from women’s groups, but we found very little representation of women and when we did, it tended to be village midwives or a possible representative from the state corporatist Family Welfare and Empowerment organisation (PKK). However, in those instances where there were other women participating in the COVID-19 Taskforces from outside these conventional groups, they tended to be from groups which had previously grown their influence in the village with the support of empowerment-focused CSOs.

Decisions on village development and use of the Village Fund are also made in village meetings. The COVID-19 crisis disrupted the status quo of villager participation in these meetings. This presents both opportunities and threats for growing women’s voice and influence. While some areas in Indonesia have a prior history of women’s groups that have diverse, skilled, vocal, and influential women, this is not uniformly the case across Indonesia and in many areas, women have long been excluded from development decision making and priorities.

As expected, our survey found that men were more likely to attend village meetings. However, there were quite high levels of meeting attendance among women in places where significant women’s empowerment work had previously taken place, with 64 percent of women reporting that they attend village meetings when they know about them. Further, more women with a background of working with CSOs attended these meetings compared with other women. Indeed, women’s organisations involved in our collaborative research have reported that in areas where significant community organising had already taken place through women’s groups, unions, networks, informal spaces and support for women, women in many instances were the first to move in the COVID-19 response in communities.

Women and local responses to COVID-19

Our partner organisations have identified persistent challenges on how to: halt reversals in gender parity, determine what forms of support will withstand shocks over the long term in tackling gender equality, augment women’s own resilience, and capture and share learning from across their women’s empowerment programs.

In some areas where women had already experienced prior CSO support, groups moved quickly to respond to impacts of the pandemic and to support each other and their communities. Groups of homeworkers, for instance, pivoted early in the pandemic to develop their own businesses when factories ceased to provide them with piecework. In Deli Serdang, on the urban fringe of the capital of North Sumatra province, with the support of the CSO BITRA, women homeworkers produced new businesses, including creatively decorated personal protective equipment and fabric face masks. These businesses drew on skills and networks and expanded groups, with the Maju Jaya Collection earning around $280 Australian dollars a worker in 2020, or Rp. 2.8 million, which is equivalent to just over a month of income (if measured against the minimum monthly wage for the region). A leader of the Prosperous Homeworkers Union (Serikat Pekerja Rumahan, Sejahtera (SPR) explained that pivoting was a response to limited government assistance: ‘we were forced to be more creative and open business opportunities [for ourselves]. If we didn’t, we would be fully reliant on government assistance. It is not guaranteed that we would receive it and even if we did it is only a small amount.’ This emphasis on self-reliance was also reflected in campaigns from the CSO BITRA that encouraged women to grow their own vegetables to safeguard their family’s food security and nutrition in 2021.

Homeworker groups in North Sumatra too played important roles in providing village governments with data on those in need of Village Fund direct cash transfers. Leader *Mia (pseudonyms for individuals are used throughout) recounted how she provided union data on families impacted by unemployment: ‘[They were] those who didn’t have work and their husbands were not working among other reasons, after that it was agreed and around 60 percent of union members received the support.’ These types of group initiatives built on prior work to improve access to social protection by working together with government agencies to provide members of marginalised groups with the identity documents necessary to access social protection programs.

Women have often taken on leadership roles in the COVID-19 response while also managing the challenges faced by themselves and their families during the crisis. Some groups are particularly vulnerable. Partner organisations in our study report that this is particularly the case for female-headed families—who often experience the highest levels of impoverishment and are often not included in or reached by other social protection initiatives—and homeworkers (as the factories and businesses they supply shut down), and for women creating livelihoods in the informal sector, among others.

Female-headed families—one of the most stigmatised, difficult to reach and poor groups in Indonesia—have managed to be reached in the cash transfer program mentioned above, again particularly in areas where such women were members of women’s groups. At the end of June 2020, the Minister for Villages, Transmigration and Disadvantaged Areas Development announced to the national parliament that 27 percent of the cash transfers made in the first tranche had reached female-headed families, This significant policy achievement resulted from national advocacy work by PEKKA and other women’s organisations, as well as the willingness of the Indonesian government to rely on local knowledge to identify those community members who were so poor that they fell through the gaps in other long and short-term social welfare and poverty reduction programs. Despite this targeting, research conducted by PEKKA suggests that by the end of 2020 only 22 percent of Indonesian villages had specific policies for supporting female heads of families during the pandemic, further indicating the unevenness of inclusive policies across Indonesia’s multi-level governance system and the continued efforts that need to be made to reach Indonesia’s most disadvantaged groups. No further data is currently available.

Women leaders and groups, at both the national and local levels, have also played important roles in ensuring that families in need receive government assistance, particularly members of vulnerable groups. In Madura, East Java, for example, the local village PEKKA union groups assisted women from female-headed families and others to apply for social assistance for establishing or growing micro-enterprises (a jointly funded initiative from the Ministry of Women’s Empowerment and Child Protection and the Ministry of Cooperatives and Small and Medium Enterprises) during the pandemic. Again, this is an achievement, as people from these vulnerable groups rarely access such government programs. District PEKKA union leaders also co-ordinated with the bank branch responsible for processing the payments to resolve inconsistencies in recipient biodata and enable the smooth delivery of funds. Local village PEKKA union leaders also accompanied and supported fellow villagers to process their government assistance payments at the bank. This was important for ensuring access by vulnerable groups, as many women from Indonesia’s poorest and vulnerable groups have explained to us time and again that they are fearful of engaging with government or formal institutions, having little knowledge of how these systems work and having experienced significant social stigma and shame as a result of their poverty. This is one of the reasons they fall through the cracks of wider social protection systems and programs.

Others were affected too by the pandemic and required additional assistance, even those who have traditionally managed to sustain their livelihoods or access government support. For example, *Ati, a PEKKA union group village coordinator (pseudonym) first interviewed in our original research collected data on group members experiencing reduced income as a result of the pandemic, assisted some members to collect assistance payments from the bank and others to process their identity cards to access support. Ati herself experienced a significant loss of income for her business (wedding sound system and clothing) as public health measures restricted events, especially in the busy seasons around the holy month of Ramadan and religious holiday Eid al-Adha. Her family relied on the small amount of rice they grew, her husband’s welding repair business and borrowed money. They also received government food assistance. Ati stated that despite this hardship, she was not categorised as poor and did not receive a Village Fund cash transfer. ‘I have been affected so much. My mum’s kiosk in Surabaya has closed, my business here has closed’. Group savings and loans have been a focus of the PEKKA group Ati helped to form in 2015. During the pandemic their Qur’an reading group continued to meet, and members contributed small amounts of money each meeting. Ati borrowed from this small fund to support her family. Ati reflected on the value of the group during the pandemic: ‘I can deal with this, I’m OK even though I’m sad. I am just grateful that I enjoy my activities. I love the activities and organising … I don’t spend too much time worrying about money’.

Our research shows that when women who had developed their skills with CSO support were included on COVID-19 taskforces, they implemented innovative responses for their local communities. In our research village in central Lombok, West Nusa Tenggara province, two women DESBUMI (Villages that Care for Migrant Workers) cadres were part of the village’s COVID-19 taskforce. DESBUMI cadres built on their previous collection of data on mobility and employment that captured migrant worker movements and was used to advocate for village regulation, which was supported by the CSO Migrant CARE and its local partner the Panca Karsa Association. One of the DESBUMI cadres documented returned migrant workers and oversaw quarantine for those recently returned and COVID positive villagers, while the other managed the data on recipients of cash assistance. She recalled how, in determining who would receive assistance, the village taskforce sought to prioritise the most vulnerable: ‘We chose the elderly, those who didn’t have income, those who were truly very affected.’ The village government also requested that the women former migrant worker group La Tansa make 1,000 COVID-19 face masks to distribute.

Conclusion

COVID-19 has constituted a critical juncture in which new challenges and opportunities for communities have emerged, particularly for women. Our pre-pandemic research identified pathways by which village women—through group structures and membership, networks and collective action, and with the direct support of CSOs as well as their advocacy—have managed to overcome constraints and barriers to influence village development in even the most difficult and restrictive contexts for women. This indicates the possibilities offered by deep, long-term grassroots women’s empowerment.

While there has been significant backsliding during the pandemic of prior gains made to close the gender gap, our research also shows that women who had developed their skills, networks, knowledge, and confidence through CSO empowerment programs were both well placed and among the first to respond to the pandemic in many instances. But little attention was given to gender representation and harnessing this knowledge in the structure and make up of COVID-19 taskforces, beyond the conventional PKK and midwife representation.

Early pandemic research also shows that some Indonesian women have displayed resilience— understood here as decisions and resources that enable long-term wellbeing and welfare— using their influence to shape the pandemic response, especially participants in prior empowerment programs, although patterns in resilience have been uneven across locations and groups.

A key element of resilience is building back stronger, rather than focusing on short-term coping strategies. Other regions could learn from these experiences of the importance of community organising through women’s groups to ensure that responses reach those who need it, including the most vulnerable. Continued support for wide-reaching, gender inclusive development initiatives is critical to respond to regressions of the hard-won, grassroots gains to improve gender-inclusiveness and work toward durable structural changes to support gender equity.

Authors: Associate Professor Rachael Diprose, Dr Ken M.P. Setiawan, and Bronwyn Beech Jones.

This research on the impacts of the pandemic on rural Indonesian women was conducted independently by the authors and partners, supported by a grant from the Faculty of Arts, the University of Melbourne.

We would also like to thank our research partners from PolGov in the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences (FISIPOL) at Universitas Gadjah Mada for their contribution to this collaborative research project on the impact of the pandemic, also under the co-leadership of A/Prof Amalinda Savirani with A/Prof Rachael Diprose and Dr Ken Setiawan for the UoM Faculty of Arts grant. We are grateful for research inputs and valuable insights from A/Prof Savirani and researchers Azifah R. Astrina, Longgina Novadona Bayo, Devy Dhian Cahyati, Indah Surya Wardhani, Mustaghfiroh Rahayu and Ulya Jamson.

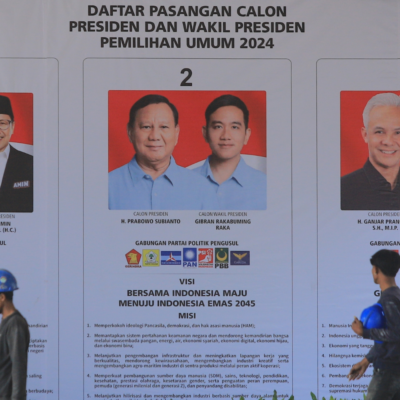

Image: Women homeworkers in North Sumatra, December 2020. Credit: Devy Dhian Cahyati.

*Pseudonyms are used for individuals throughout.