At varying times over the past 15 years, Facebook and other social media sites have been idealised by pundits, media, Western governments, and the tech industry as a tool catalysing democratic change during periods of political unrest in authoritarian countries. The events of the Arab Spring, in particular, propelled social media to the front lines of global attention as a potential democratising tool.

This optimism about social media is built into Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s extended 2017 manifesto ‘Building Global Community’, where he argues that Facebook helps to build ‘supportive…safe…informed…civically engaged and inclusive communities’. In a 2018 Facebook series on social media and democracy, a Facebook Civic Engagement manager said that, ‘I believe that a more connected world can be a more democratic one’.

Yet when Facebook is used as a platform for hate speech and organised violence, the company has been quick to deflect blame from the platform and stress the role of its users. Thus, when used towards liberal democratic ends it is often alleged that it is the platform’s influence, and when use is illiberal or anti-democratic, it is the result of bad users in a specific context.

We draw on the example of Facebook in Myanmar and seek to emphasise the opposite: when Facebook is used for democratic organising, such as following Myanmar’s recent coup, then the agency, bravery and creativity of individual users—who face significant barriers and risks when utilising the platform—ought to be recognised by the media and public. Conversely, when Facebook is used as a platform for hate speech, as it was by illiberal anti-Muslim movements in Myanmar, then Facebook’s preparations, practices, and policies require greater scrutiny. We conclude that it is crucial in developing countries to recognise and question narratives of digital ‘solutionism’: optimistic narratives that assume technological solutions to complex social, political and economic challenges.

Facebook’s growth in Myanmar

The pace of Facebook’s spread in Myanmar in the early 2010s was extraordinary. Market research companies estimated that there were 1.2 million Facebook users in Myanmar in 2014. Yet by January 2019 there were 21 million Facebook users in Myanmar which is around 40 percent of the country’s population. Crucially, Facebook enjoyed an almost monopoly of social media usage, accounting for more than 99 percent of the social media market in Myanmar. One Yangon cyber security analyst said that ‘Facebook is arguably the only source of information online for the majority in Myanmar’.

There are several reasons Facebook enjoys such dominance in Myanmar. Facebook’s ‘Free Basics’ initiative in the developing world and partnerships with telecommunications providers such as Norway’s Telenor helped fuel Facebook’s extraordinary expansion. After its entry in 2014, Telenor offered a deal where customers could use Facebook on their mobile device without any data charges. Importantly, as internet connectivity was expanding, the quality of connections remained poor, but in this early phase of expansion Facebook loaded better than other platforms. Lastly, Facebook established deals with manufacturers and retailers to have Facebook preloaded on to Burmese mobile phones.

Using Facebook for resistance following the 2021 Myanmar coup

In the early hours of February 1, 2021, Myanmar State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, President Win Nyint and many other National League for Democracy (NLD) Members of Parliament were arrested by the Burmese military. A statement from the military declared that power had been transferred to commander-in-chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing and that the country would be under a state of emergency for the next 12 months. New so-called ‘free and fair elections’ would take place due to claims of fraud and so-called ‘huge irregularities’ in the NLD’s landslide election victory in November 2020.

The military coup sparked immediate resistance from Burmese political parties, civil society groups, and citizens from all over Myanmar. An NLD statement under Aung San Suu Kyi’s name, released a day after the coup, urged people ‘not to accept this, to respond and wholeheartedly to protest against the coup by the military’. Large scale street protests began in all major cities, with protesters using a three finger salute of resistance inspired by the book The Hunger Games. A broad civil disobedience movement also emerged, with government-employed doctors, engineers, academics and civil servants refusing to work under the new regime. Despite escalating violent military crackdowns through late February and March—with thousands of arrests and hundreds of civilians killed—the protests continued in major cities.

In the weeks following the coup, protestors and activist networks made wide use of Facebook as a platform for mutual encouragement, information sharing and news updates. After 19-year-old Kyal Sin was shot dead while protesting in Yangon in early March, photos of her had millions of views on Facebook. On the day of her death she was wearing a t-shirt saying ‘Everything will be OK’. As photographs of her spread on Facebook, there were thousands of comments supporting the protesters and overall resistance to the coup. In the early weeks of the protests, photographs of others who had been arrested, wounded or killed in the crackdown were also widely shared.

Facebook posts from protesters used humorous references to international pop culture while others contained practical advice, for example on protest tactics or how to safely carry wounded people. Some posts personally identified and shamed individual police officers who had been involved in the crackdown, while others urged government workers to join the emerging civil disobedience movement. With such widespread activity on Facebook, the Myanmar military began to identify and seek the arrest of opposition Facebook users and attempted to block all social media use. This did not stop users however, who made creative use of VPNs (Virtual Private Networks) to continue accessing the platform.

These tactics are reminiscent of others that have played out since the Iranian so-called ‘Twitter Revolution’ in 2009, and then in Egypt, Ukraine, Venezuela, and most recently, Thailand. However, they demonstrate more than just the broader mimicry of digital protest repertoires since the social media age. They also highlight how protesters can adopt and adapt strategies in innovative ways that can take advantage of platform affordances and cultural contexts while also circumventing structural barriers implemented by much more powerful actors, such as when authorities begin censoring, surveilling, or blocking social media or employing violent countermeasures on the streets. While Facebook and Instagram deserve some credit for banning Myanmar’s military on their platforms, they do not assume the same risks as their users, who often face significant danger when deploying the above. It is the creativity and bravery of users which ought to be celebrated.

Facebook’s facilitation of hate speech in Myanmar

Despite this recent use of Facebook by democracy activists, the longer history of Facebook in Myanmar highlights its role in facilitating illiberal movements. During its entry into Burmese society, Facebook had extremely limited capacity to monitor Burmese language posts and then failed to respond to early warnings of illiberal organising on its platform. Yet assessments that followed the increase in hate speech on Facebook in Myanmar primarily spotlighted ‘bad users’ rather than the company’s own practices.

The liberalisation of the Myanmar economy and easing of Western sanctions after 2011, which allowed the entry of Facebook, also coincided with liberalisation in freedoms of speech and association in Myanmar. Public debate about social issues, which had been smothered for decades by rigid military authoritarianism, began anew in Myanmar’s print media, online, and in teashops around the country. On one hand this allowed new political associations such as labor and environmental movements to flourish.

But there was a widespread perception amongst the majority Burman population of a ‘Muslim threat’. The presence of Muslim majority countries in Myanmar’s region, and a perceived growth in Muslim populations within Myanmar, especially in Rakhine State, contributed to fears for ‘race and religion’, and therefore the future existence of the Burman and predominantly Buddhist population of Myanmar.

Leading into Facebook’s rapid penetration into the Burmese market, there were no indications that the company considered in any capacity the impact its platform would have on Burmese society. And as the number of Facebook users grew to the millions, there were clear warnings for the company that the platform was facilitating hate speech against Muslims. As early as 2013 Myanmar Deputy Minister for Information, U Ye Htut, reflected that Facebook spreads ‘gunpowder’ through the country through rumors and the proliferation of hate speech. Following incidents of violence in 2014, civil society groups, researchers and tech entrepreneurs communicated with Facebook officials a number of times, stressing the widespread use of the platform for hate speech, especially through fake accounts. One specific example of a post on the platform that was identified for Facebook by civil society groups said, ‘We will genocide all of the Muslims and feed them to the dogs’.

Despite these criticisms, by 2015 Facebook still had virtually no capacity for identifying hate speech on its platform in Myanmar, either through natural language processing or through human analysts. In 2015, Facebook had only two Burmese speaking analysts dealing millions of daily posts in Burmese language. This meant that most of the identification of hate speech on the platform relied on Burmese Facebook users themselves.

As military and civilian violence against Muslims in Myanmar reached a peak in 2016 and 2017, hate speech on Facebook proliferated. Attacks by an insurgent group in Rakhine state in October 2016 led to major reprisals against Muslim communities, primarily led by the Burmese military. A year later another insurgent attack on police stations in Rakhine state led to even more widespread and violent military operations against Muslim communities which ultimately displaced almost one million people from Rakhine state to neighbouring Bangladesh. Propelled especially by sermons from prominent monks such as Ashin Wirathu, Burmese language anti Muslim hate speech spread widely online.

Following the Rakhine crisis in 2017, the United Nations initiated an ‘independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar’, which included investigation into the role of Facebook in the crisis. The report found that ‘Facebook has been a useful instrument for those seeking to spread hate’, and that its response had been ‘slow and ineffective’. The proliferation of hate speech on Facebook in Myanmar was clearly counter to the narrative that Facebook was building ‘civically-minded’ and ‘inclusive’ global communities.

Yet when highlighted by the United Nations as being a ‘useful instrument for those seeking to spread hate’ Facebook redirected criticism away from the platform, instead blaming local individuals, groups and culture. In 2018, Facebook commissioned a consultancy firm to do a so-called independent assessment of the company’s human rights impact in Myanmar. Much of the report focuses on perceived challenges in Myanmar, redirecting blame from the role of the platform, to the domestic context—a lack of ‘digital literacy’, an undeveloped regulatory environment and cultural beliefs that reinforce discrimination—and ‘bad actors’ who use Facebook. The emphasis of the assessment is not so much on the inadequate capacity to monitor Burmese language or the widespread failures of Facebook to respond to hate speech in Myanmar, but rather the shortcomings of its users.

The dangers of digital solutionism

Critics of Facebook’s role as a platform for hate speech against Muslim minorities in Myanmar rightly point to a range of practical steps that ought to be taken. For example, if Myanmar returns to a democratic form of government in the future then a stronger legal framework around social media use would be important. Strengthening Facebook’s Burmese content regulation would also be crucial, through improved Burmese natural language processing and higher numbers of human analysts to monitor and remove Burmese language content . However, a more active role in moderating content in turn raises challenging new questions (especially now under an authoritarian regime) about how Facebook ought to intervene in controlling the content of users. What lines should Facebook draw on moderating content, for example, of ethnic armed groups, or other violent movements who oppose the authoritarian government?

It is also important however to examine the wider narratives surrounding Facebook’s actions in Myanmar. This can be illuminated to some degree through what writer and researcher Evgeny Morozov describes as ‘the folly of technological solutionism’: a widespread techno-deterministic narrative within industry, media and the public that societies can be free of social or political problems given the right applications of technological solutions. The rapid spread of technological affordances from, for example, the United States, Japan or Europe, to poorer countries such as Myanmar, and the role of technology companies in driving this, tends to be wrapped in an assumption of the inherent social, economic and cultural value of these affordances.

Crucially, a narrative of digital ‘solutionism’ serves to ascribe agentic characteristics to different actors. In the case of positive outcomes, proponents of this narrative can ascribe those outcomes to the active intervention of companies and their digital affordances. Meanwhile, Facebook users are either bad agents who exploit technologies for nefarious purposes or are passive participants in the actual fight between technological progress and tyrannical states. In the case of Myanmar, Facebook could be both an active protagonist (in the fight for democracy) and an innocent observer (in the proliferation of hate speech).

Such narratives have real world impact and in the case of Facebook’s role in Myanmar, the stakes are incredibly high. Facebook has had a virtual monopoly on social media use, and online information sharing, in a country with profound ongoing poverty and economic vulnerability. Therefore, questioning digital solutionism is crucial in both celebrating the creativity and bravery of Myanmar users, and refusing to allow Facebook to deflect responsibility for facilitating hate speech.

This examination and critique of narratives of digital solutionism is also important beyond the case of Facebook in Myanmar. New waves of digital products will inevitably be introduced to Myanmar and other countries on the margins of the global economy, under both authoritarian and democratic regimes of the future. The case of Facebook demonstrates the dangers of unchecked narratives of digital solutionism and the associated overconfidence of companies as technological affordances transfer to new and vulnerable contexts.

Myanmar’s political and economic future has become highly uncertain since the military coup. Heightened awareness of the dangers of digital solutionism may serve to help protect against future problems. As well as celebrating and supporting the agency, creativity and bravery of democracy activists we ought to focus more on Facebook’s responsibility in managing its operations ethically and protecting those who may be at risk. Mark Zuckerberg hopes the platform can build ‘civically engaged and inclusive communities’. Yet this is unlikely if Facebook continues to deflect attention from its failures in the societies in which it has an influential presence.

Authors: Dr Tamas Wells and Dr Aleks Deejay

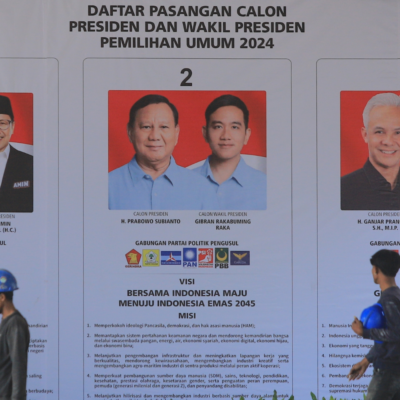

Image: People using smartphones, Yangon Myanmar, 2015. Credit: Remko Tanis/Flickr.