Our research indicates that Chinese international students have difficulty reporting racism to their universities.

We also find that Chinese international students lack confidence that their universities will support them in tackling racism on campus and beyond. This exacerbates the ongoing injustice and struggles experienced by (Chinese) international students in Australia.

Further, the lack of systematic and genuine institutional support from universities leads to the isolation of students from campus life and wider society.

Chinese international students in Australia – a brief background

International students form a significant proportion of Australia’s higher education sector. According to the Australian Government’s Department of Education, between January and November 2024, almost 850,000 international students studied in Australia, with nearly half enrolled in higher education. This includes 24.82 percent from Mainland China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan, and Malaysians of Chinese heritage. In 2023, international students made up 32.78 percent of the total higher education student population in Australia, a proportion that increases when including commencing students.

Australia’s international education sector plays a significant role in building relationships with Asia. Many alumni of Australian universities become informal ambassadors for Australia when they return to their countries of origin, and others remain in and contribute to Australian society.

However, an interim Respect at Uni report in December 2024 by the Australian Human Rights Commission highlighted systemic and overt racism affecting students and staff from Asian backgrounds. Racism against Chinese and Asian migrants in Australia can be traced back to the Gold Rush era (1851-53) and became acute after the election of Pauline Hanson to Australian Parliament in 1996. Such sentiments flared up again during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia and abroad. Studies have found that international students were the most impacted group as they faced various forms of prejudice, racism and workplace exploitation.

Concerningly, several barriers discouraged Asian Australians from actively reporting incidents of racism during this period. These included a lack of trust in authorities, feelings of disempowerment, and limited knowledge of, or access to, relevant support services. For international students, the challenges were even greater. Many felt unsupported and feared that speaking out could jeopardise their visa status or even lead to deportation.

Further, racism has evolved into more covert forms, including racial microaggressions, also referred to as everyday racism, which include indirect or unintentional acts of discrimination that cause emotional distress and exclusion. The sometimes subtle nature of microaggressions makes them harder to identify and report, further complicating international students’ experiences.

When international students encounter racism, it can impact Australia’s international reputation and its international education industry. For example, in 2009 at the height of racist attacks on Indian international students, Australia’s reputation in India particularly was impacted and the number of Indian students coming to Australia declined.

Our research

In 2024, we researched Chinese international students’ experiences with racism and reporting racism. Our study included students who self-identified as ‘Chinese’ (hua ren, 华人) and were enrolled in or had recently graduated (within one year) from their universities, all Melbourne-based.

Using data from an online survey (valid N=85) and qualitative insights from five focus groups (N=19), we examined the nature and prevalence of racial discrimination and evaluated the effectiveness of institutional mechanisms in addressing these issues. We received 119 responses and 85 interviewees completed all questions. Most of the 85 valid respondents came from mainland China (n=66) and spoke Mandarin (n=75) at home. The majority of respondents (72 percent) were 18-24 years old (n=72) and were studying an undergraduate degree (including an Honours degree) (n=53, 61 percent).

A total of 19 students participated in the focus group facilitated by two of the authors. Topics discussed in the focus group centred on unpacking the main findings from the survey. While focus group participants’ demographic features such as age group, language and home country/region were mostly consistent with the pattern of the survey respondents, most focus group participants (n=14) were undertaking postgraduate (including PhD) degrees.

Chinese international students’ experience with racism

In relation to their experience with racism, 65 percent of respondents (n=55) reported that they had experienced some form of racial discrimination or bias during their study.

During the focus groups, participants shared personal encounters with racism. Of the 19 participants, 16 recounted at least two instances of racial discrimination totalling 41 stories. Most commonly, this racism took the form of explicitly offensive remarks, such as being told to ‘go back to your country,’ often occurring in public spaces such as streets and public transport.

In relation to incidents on university campuses, the experience mainly took the form of everyday racism or microaggressions.

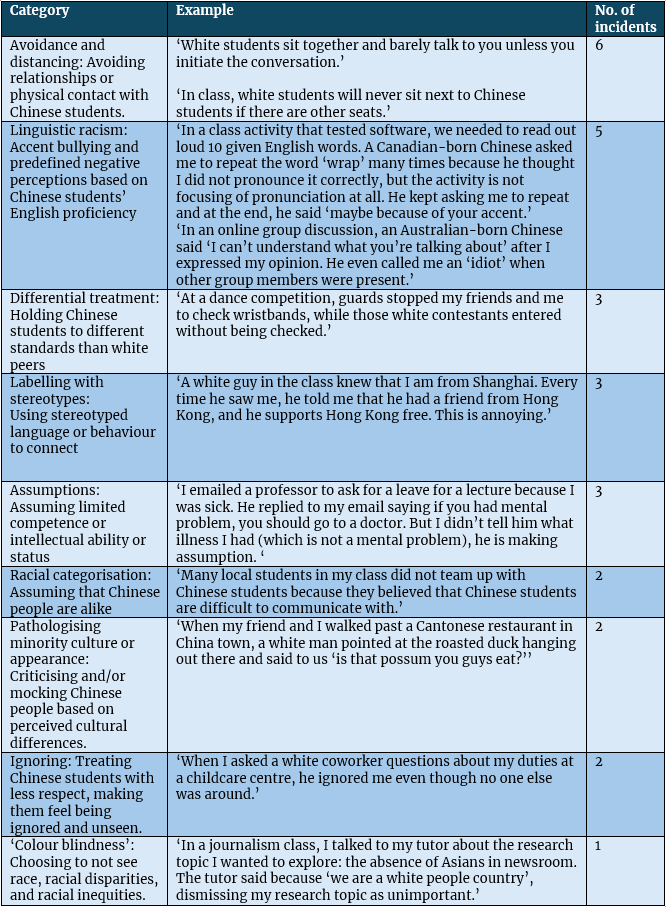

Table 1. Microaggressions reported by participants

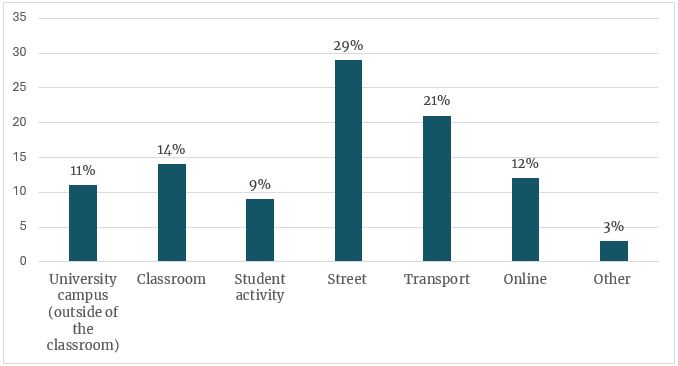

Approximately half of the incidents took place outside of university campuses and place on campus (a multi-select question).

Figure 1. The respondents’ answers to the question ‘Where did racism take place?’

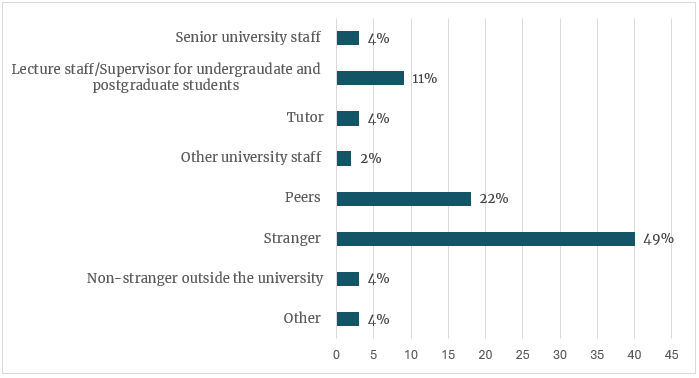

A further multi-select question reveals that peers and teaching staff at universities were among the perpetrators (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Different types of perpetrators

Did students seek help from their universities?

Both the survey data and focus group discussions reveal that most participants did not report their experiences to their universities or other authorities, such as the police. Out of the 85 survey respondents, only 10 percent indicated that they reported incidents of racial discrimination or bias to their university.

The situation was similar in the focus groups: of the 19 focus group participants, only one reported a racist incident to their university.

The reluctance to seek support extends beyond commonly cited barriers such as lack of awareness, difficulty accessing services, perceived insignificance of incidents, language or cultural barriers, and embarrassment.

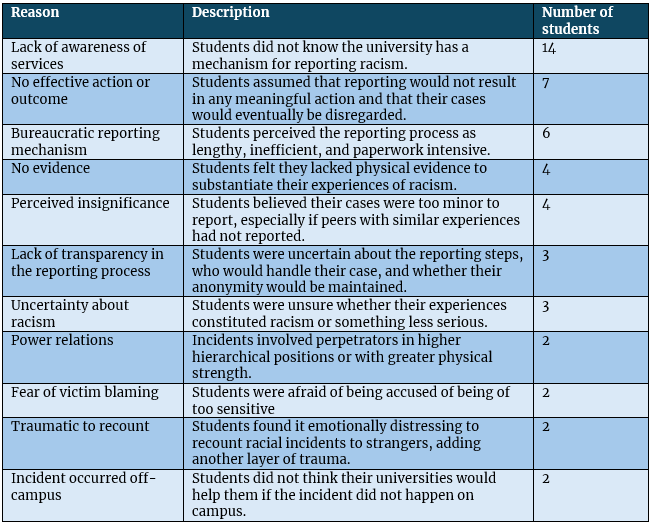

Table 2. Reasons students chose not to report

These findings reveal a systemic issue in relation to reporting racism within the universities. While universities publicly advocate a zero-tolerance stance on racism, their systems and practices often fail to reflect this commitment.

The lack of trust in reporting mechanisms, combined with the perception of racism as a common experience and therefore something that has to be endured, discouraged students from engaging with what they saw as an ineffective and bureaucratic process, leaving them feeling powerless against systemic racism.

Reflection and recommendations

The study highlights the significant burden placed on Chinese international students when deciding whether to report racism. We are concerned that the consequences of microaggressions can significantly affect the mental health and opportunities in life of those targeted.

Indeed, reflecting on the reasons outlined in Table 2, it is clear that a different approach is needed to encourage students to report such incidents by removing bureaucratic burdens, promoting students’ rights and voices, and developing protective mechanisms to ensure their safety and wellbeing

Our recommendations include:

- Data Collection – Universities should systematically gather data on students’ experiences with racism to inform policy changes.

- Governance and Transparency – Stronger governance structures should be established to ensure accountability in addressing racism.

- Improved Communication – Universities must enhance communication regarding international students’ rights and available support services.

- External Support Systems – Collaboration with external organisations such as student advocacy and student services, health services for people of Chinese speaking backgrounds, and youth mental health service providers to help build trust and provide students with alternative avenues for reporting incidents without fear or intimidation.

- Mandatory Anti-Racism Training – Regular and compulsory training for all staff, including bystander intervention strategies, can help create a more inclusive environment. This should be provided by people with lived experience.

Addressing these systemic issues requires a proactive and sustained effort by universities to foster a truly inclusive and supportive educational environment for international students and improve Australia’s reputation internationally.

Authors: Dr Wesa Chau, Dr Wilfred Yang Wang, Dr Juerong Qiu and Dr Andrew Duecher.

This work was supported by the Anti-Racism Hallmark Research Initiative from the University of Melbourne.

Image: Students at Sydney University. Credit: SydneyUni/Flickr.