It was a ritual that was simple, quickly done, and telling in its details.

Everyone locked in the humid, crowded cell of 11 men of varying ages had to answer a sharply asked question in Malay, “kau salah apa?” (what did you do wrong?). Some grunted in response to each tale of woe, while some were asked for more details in follow-up questioning.

For me, after decades of sticking diligently to the journalists’ maxim that ‘you are not the story’, it was a jarring moment. How to not sound awkward and explain my arrest earlier that day for my banned book, after hearing the alleged tales of the other men: a teenage Rohingya labourer detained because of a drunken brawl, the Chinese triad gangster’s online gambling scams, the Javanese bloke’s deadly use of sharp knives, and an Egyptian tourist’s mistaken bagful of shoplifted Puma jerseys?

Moreover, according to these cellmates, the only way books or any printed material could possibly be prohibited would be for salacious pornographic content, which seemed quite a contrast to the mostly academic essays that made up our book “Rebirth: reformasi, resistance and hope in new Malaysia”.

As I explained in follow-up questions from a few migrant workers and gang members inside, the book had been banned three years earlier. It was during Malaysia’s unprecedented socio-political turmoil of a global pandemic, tough lockdowns, and what turned out to be four federal governments in five years. The new government found the book “potentially prejudicial to public order, security, and national interest” when it was banned in July 2020, and the case was investigated for alleged violations of laws on national emblems, sedition, printing presses and publications, and communications and multimedia.

Three years later, my arrest and detention over 36 hours in a Kuala Lumpur cell was after returning to Malaysia for the first time since the pandemic’s border closures to renew my passport, and my lawyers were unaware that there were questions still to answer in the case.

Moreover, there was surprise in 2023 under the new Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim that the previously renowned ‘reformasi’ leader, who had long campaigned for democratic change and against archaic laws such as the colonial-era Sedition Act and the Printing Presses and Publications Act, would maintain such laws despite earlier promises to repeal them. These laws are often used as weapons to silence critics and restrict freedom of expression (not least against Anwar when he was in opposition), and frequently in concert with the much newer Communications and Multimedia Act of 1998.

The challenges to Malaysia’s freedom of expression and the prevailing censorship regime haven’t diminished in 2025. Geopolitical uncertainty, the great power contest between China and the United States, and the collapsing “liberal rules-based order” that previously enabled democratic spaces in the region, have also been seen as an unhelpful backdrop stifling more Malaysian reforms and media freedoms. The momentum for legislative reforms once promised by Anwar’s Pakatan Harapan coalition has stalled, as it heads into its third year as a “unity” or “Madani” government with former foes, the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), its Barisan Nasional coalition, and the Borneo parties coalesced under the Sarawak Parties Alliance (GPS) and Sabah People’s Coalition (GRS) banners.

While Malaysia’s legacy media industry is financially distressed, despite its owners’ and tycoons’ close ties with political parties in power, and their leverage still compromised by a national economy recovering from the pandemic and today’s tariff wars, there isa burgeoning appetite for ‘free’ social media rumours and online news. This new media environment has not been matched by government and community demands for better factual rigour, especially over contentious issues known as the 3Rs of “religion, race and royalty”.

As the recent Centre for Independent Journalism (CIJ Malaysia) 2025 report notes, Malaysia’s media landscape remains “heavily constrained by political control, economic instability, and an oppressive legal framework”. It adds substantive change remains elusive.“Media freedom continues to be stifled by legislative overreach, selective enforcement, economic pressures, exacerbating self-censorship and eroding public trust,” it notes. “Unethical and sensationalist reporting further undermines responsible journalism, particularly in sensitive areas such as gender, race, religion, and migrant issues.”

Yet one positive development many Malaysian journalists had long campaigned for became legislative reality in February this year, when the Malaysian Media Council (MMC) Bill passed parliament. The Council enables media self-regulation for the first time in Malaysia’s history, and should exist with a concurrent repeal of repressive laws such as the Sedition Act of 1948, the Printing Presses and Publications Act (PPPA) of 1984, the Official Secrets Act of 1972, and the Communications and Multimedia Act of 1998 (and its subsequent provisions). But such laws remain in place.

The Media Council has been touted as a key way to reform Malaysia’s legal framework for freedom of expression and the media. Anwar’s Madani government had previously announced its intentions to amend problematic sections of the Communications and Multimedia Act 1998 and repeal the draconian Sedition Act 1948, neither of which have been delivered.

For the Media Council’s interim chairperson Premesh Chandran, the co-founder of stalwart independent news organisation Malaysiakini, the imperative now for Malaysian media and freedom of expression is not to make “perfect the enemy of the good”. The structure of the Council is not the ideal outcome—there will be government representation and input—but the Council can “evolve” and improve in independence and capacity.

Abolishing repressive laws would be made easier with an independent Media Council, as new media council members explained to me, but the fragility of coalition politics in Anwar’s government and on-going financial crises of Malaysia’s broadcast and publishing sectors are more urgent concerns.

As the leadership of Malaysia’s National Union of Journalists (NUJM) made plain to me recently, after a fruitful exchange program between Indonesia’s biggest journalists’ union AJI and NUJM that I co-led for the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), “we don’t want media owners to simply retrench hardworking journalists because the business model is ‘not working’… we don’t want to lose good journalists now and in the future due to the decline in jobs, when we have struggled hard since 1973 to form a media council.”

In our IFJ discussions with media colleagues and civil society groups engaged by AJI in Yogyajakarta, Semarang and Jakarta, it’s not just repressive laws and the legacies of authoritarian politics and laws in both Malaysia and Indonesia that plague efforts for a better media and freedom of expression.

There are deep-seated structural issues of media financial sustainability, and significant barriers to genuine self-regulation and ethical journalism, in the wake of social media quagmires and disinformation campaigns fuelled by state-linked actors and big-tech algorithms. In this era of information deluge and weaponisation, where much is not what it seems and facts are optional, banning books and febrile campaigns against legacy media may be sideshows of a looming bigger opera.

Kean Wong is a journalist, editor and researcher in Sydney, a co-founder of the Centre for Independent Journalism (CIJ) Malaysia, and a board member of Media Diversity Australia; https://bit.ly/anumikmw.

This article is part of a special series on media freedom in Southeast Asia to mark this year’s Southeast Asia Oration by Nobel Peace Prize winning journalist Maria Ressa, hosted by Asialink and Asia Institute, University of Melbourne, on Thursday August 28, 2025. The special series is a joint initiative of Asialink Insights and Melbourne Asia Review.

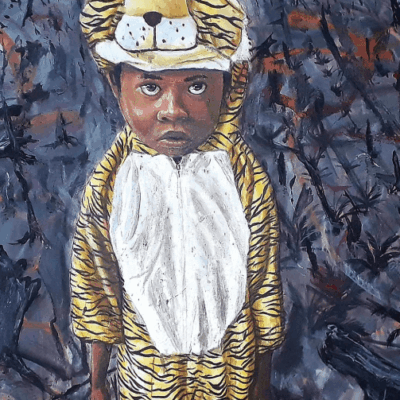

Image: Lines of barbed wire against a cloudy sky. Photo by Robert Klank on Unsplash. The original image published with this article was replaced.