In 2015, a group of young and ‘cool’ Japanese college students known as the ‘Student Emergency Action for Liberal Democracy’ (SEALDs), captured the nation’s attention through a series of vibrant street protests in opposition to the administration of Shinzo Abe’s controversial set of security bills, attacks on free speech, and a disregard for the democratic process.

One of the notable aspects of SEALDs, beyond their ability to mobilise the largest crowds at demonstrations since the 1970s, was their capacity to simultaneously navigate mainstream and social media platforms, making them widely recognisable to the Japanese public. However, their notoriety also drew detractors on the Internet in message boards and Twitter accounts popular with Japan’s online right-wingers know as the ‘netouyo.’

The online backlash towards the movement included trolling, exposing personal details of members’ lives, and threats of physical and sexual violence. While netouyo attacked both male and female SEALDs members, the attack lines were often racialised and gendered in distinct ways to delegitimise the student group’s broader political message.

SEALDs seemingly came out of nowhere in the summer of 2015. Initially gaining attention through street demonstrations and social media platforms, SEALDs’ activism began to be featured regularly in mainstream media. At least initially, much of the media took the student activists seriously. Several news broadcasts and variety shows celebrated SEALDs members as examples of youth’s active interest in politics. SEALDs’ energetic street demonstrations undercut the pervasive view that Japanese youth were passive, apathetic, and politically disengaged. Moreover, the student activists were educated, well-spoken and clean-cut; and unlike student activists from the past, did not voice left-wing ideology that so turns off mainstream viewers in Japan.

Since the Arab Spring in 2010 and Occupy Wall Street in 2011 revealed the power of social media for organising protest, more attention is being paid to how social media is influencing protests in places such as Japan after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011, the Indignados Movement (anti-austerity movement) in Spain, during Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protests, and the resistance to the military coup in Myanmar in February. SEALDs, too, used social media platforms like Twitter, and Facebook, to amplify their message.

Our research group on contemporary Japanese social movements at Sophia University collected oral narratives of social movement participants. Between 2015 and 2016 we conducted over 50 interviews with SEALDs members. The quotes used in this article come directly from our interviews unless indicated otherwise.

The online backlash directed at SEALDs generally played out on Twitter, popular online community 2-chan (ni-chaneru), and Facebook, among others. Most of the criticism seemed to come from online right-wingers (netouyo), a new generation of neo-nationalists congregating almost exclusively in online communities. Japanese investigative reporter Furuya Tsunehira explains that netouyo are united around anti-Korean and anti-Chinese views, a distrust of the mainstream media that they see as pushing a false liberal narrative, and a rejection of any historical criticism that Japan did anything wrong before or during the Second World War. According to surveys conducted by Tsunehira, Japanese netouyo are on average aged around 40, often college-educated, with slightly higher than average incomes. About 75 percent of them are male, and they are primarily concentrated in the urban areas in and around Tokyo. It is estimated by Tsunehira that there are somewhere between two million and 2.5 million netouyo in Japan.

While SEALDs took advantage of the speed, spread, and accessibility of social media to propel their message forward, so too did the netouyo in leveraging the same platforms with a counter-narrative by repackaging xenophobic, racist, and sexist tropes for a digital age.

Racist conspiracies

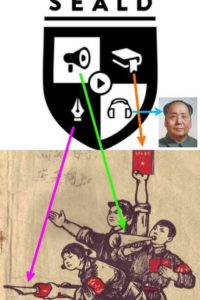

SEALDs members were accused of being communists—either overtly through membership of the Japanese Communist Party or more covertly by insinuating shadowy ties to the Chinese Communist Party or North Korea. When Japanese netouyo use the term communism it is tinged with racism towards their Chinese and Korean neighbors. Netouyo on social media boards went through elaborate exercises to decode what they saw as the embedded messaging in SEALDs’ imagery (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1

The images used are often altered or exaggerated for rhetorical purposes, or sometimes unintentionally outlandish—as in the case of the headphones symbol in the SEALDs logo being a covert image of the hairstyle of former Chinese leader Mao Zedong.

Figure 2

Another standard line of attack by netouyo was that SEALDs members were not ‘real’ Japanese. Online right-wingers drew on neo-nationalist rhetoric by assuming that any criticism of Japanese policy or politics is not a fair political critique, but is instead an assault on Japan and Japanese people. Any negative political commentary is confronted as an implicit form of anti-Japanese bias—committed by outsiders and enemies, ostensibly because ‘real’ Japanese love Japan and only express patriotic sentiments.

Many netouyo argued, with seemingly intentional distortion, that SEALDs members were foreigners or minorities. For instance, the author of the 2-chan post in Figure 3 implies that the student activists are Zainichi Korean. A broad definition of Zainichi includes Koreans who came to Japan before and during the colonial era, and those who came after 1965 when diplomatic relations were restored, including their descendants. Japanese right-wingers frequently express their resentment of Zainichi Koreans and consequently single them out for racist abuse.

In Figure 3, the author begins by stating the students’ activism could only have been started by minorities because ‘Zainichi Koreans are the only terrorists in Japan…’. The facial graphic states, ‘Please leave because you are not Japanese’. The response to this post states, ‘You are Zainchi (Korean) with no nationality. So don’t speak as if you are better than us.’ The netouyo policed the boundaries of Japanese ethnicity to delegitimise SEALD’s message.

Figure 3

In a similar way, netouyo they tried to decode the hidden communist symbolism in the student activist’s imagery by digging into the activists’ personal lives for evidence of their ‘foreignness.’ The Twitter post below (Figure 4), written by the patriotic sounding name ‘Kana who loves Japan’, presents Aki Okuda, one of the more prominent SEALDs members, next to a picture of his father, a Christian Minister. The statement reads: ‘It has been revealed that Okuda’s father is a (stupid) Korean Christian Minister.’

Figure 4

The netouyo’s tactic of digging into activists’ personal lives and then exposing them on the Internet—a form of doxing—serves the purpose of intimidating activists, damaging their reputations, and undercutting their political message. Japanese youth are hyperaware that any perceived misstep can have real-world consequences: the government and corporations blacklisted those in the student movement in the 1970s. The legacy of activists being shut out of mainstream society has had a chilling effect on youth politics at college. Through doxing, the netouyo plays on this fear. Doxing also serves the purpose of frightening anyone even thinking about political criticism.

Weaponising gender

Both male and female SEALDs members faced accusations of communist ties, being foreign agitators, or trouble making minorities, but gendered lines of attack also emerged in some striking patterns.

The male members’ political engagement, as young men, was never questioned. However, their relative status as males was. The male SEALDs members tended to be attacked for their intellectual and class status so far as could be ascertained by digging into their academic achievements. One example illustrating this dynamic was the number of posts the netouyo made about the academic ranking of the high school that Aki Okuda attended. Online trolls discovered that the school had a relatively low ranking (hensachi) of 28 on a scale of 1 to 75. The netouyo pounced on this information, using it to craft a narrative that the SEALDs members were too stupid to take seriously. The 2-chan post below (Figure 5) is titled: ‘Was Okuda’s high school really only ranked at 28!????’

Figure 5

In another case (Figure 6), an infamous character self-identifying as ‘Mr. Todai,’ posted several condescending tweets about the SEALDs members. ‘Todai’ is short for Tokyo University, the most elite university in Japan. ‘Mr. Todai’ is ostensibly positioning himself at the top of the Japanese educational hierarchy when commenting about SEALDs. He mocked a SEALDs’ poster about a student event on politics and the democratic process in Japan by stating ‘Prime Minister Abe, don’t underestimate students’—a confronting statement signaling the burgeoning power of student activists

Providing commentary on the poster, Mr. Todai seemingly transforms himself into the voice of the Prime Minister and responds to the challenge by saying: ‘Don’t underestimate me. Study before you speak. Just pay your taxes.’

Figure 6

SEALDs message to students encourages them to raise their voices. Yet, what we see in this tweet is that Mr. Todai is basically telling them to shut up. The dismissiveness towards SEALDs in his tweet is also meant as an intellectual and ideological putdown. He is essentially implying that they do not measure up, should not be taken seriously, and, presumably, that politics is an activity reserved for the elites, such as those who graduate from Tokyo University and the political class associated with it—a fundamentally elitist and undemocratic argument.

Female SEALDs members were disparaged in different ways. In addition to focusing on their class or educational backgrounds, the attacks emphasised their bodies and gender. The two cartoons (manga) drawn by the controversial artist Toshiko Hasumi and circulated online by netouyo sexualise the female SEALDs members’ political engagement in ways in which the male members were never subjected.

Figure 7

The text on the picture reads:

Let’s protect democracy.

Let’s protect the constitution.

Even though my only source is television, I know everything…

I don’t really understand what they do at the parliament (the Diet)

We threaten sound arguments and oppress speech.

The magic word is ‘racist.’

I can’t (or don’t) vote in elections.

But Japan needs to do what I say.

So, let’s do a peace demonstration.

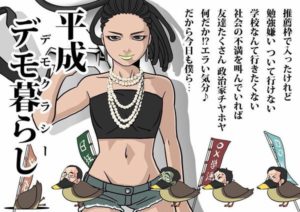

Figure 8

The text on the manga in Figure 8 reads:

I got into college through a recommendation (not the entrance exam).

But I don’t like studying, so I can’t keep up with my courses.

I don’t want to go to school.

But I’ve been screaming about my dissatisfaction with society.

Now I have lots of friends and politicians who praise me.

I don’t know why, but somehow I feel superior.

So today again, we are going to organise a demonstration.

Both mangas reduce female political participation to an adolescent popularity contest, where demonstrations are nothing more than an opportunity to show off and get attention. The suggestion is that female activists do not, or are incapable of, understanding politics. The message is that female SEALDs members are shallow, image-driven, and vacuous—essentially nothing more than social movement arm candy to the male SEALDs members.

How did the SEALDs members themselves contend with these kinds of online attacks?

In our interviews, we queried how these student activists dealt with online right-wing Internet trolling of their movement. When we asked Mana Shibata, one of the prominent female leaders of SEALDs about the netouyo, she laughed and said, ‘Yeah, they are pretty crazy,’ while changing the subject, preferring to focus our discussion on their politics and tactics. Shibata’s deflection was a strategy many SEALDs members adopted—to simply ignore them. Yet, some SEALDs members could not as comfortably disregard what was happening to them online. Some of the SEALDs members we spoke to confessed that they had stopped going to demonstrations or left the movement because the harassment became overwhelming.

Some of the SEALDs members instead drew distinctions between the online world and the physical world to manage the extremism being expressed online. As the following SEALDs member explained:

You know, it starts with responsibility. First of all, it is about whether or not you can take responsibility for what you say. To actually influence society, it is necessary to take direct action. So I feel that there is no way that society can change solely by what is said on the Internet. There might be exceptions, but I think that the possibility is very low. Actually, physically going to the parliament building and doing demonstrations has a higher potential in changing society.

By compartmentalising the online world as a distinct and less consequential political space, this SEALDs member diminishes the significance of the netouyo while elevating direct action politics in the physical world as being more important. This SEALDs member argues that their activism is more impactful since they are willing to stand behind their words and defend them with action in the physical world by organising demonstrations in front of the parliament. Unlike the netouyo, they are not hiding behind their computer screens.

Another distinction our interviewees pointed out was how their activism contrasted with the netouyo around anonymity. Many of the SEALDs members we interviewed expressed frustration that the netouyo tend to hide their own identities while going to great lengths searching for information to damage the activists’ reputations. One of the SEALDs members expressed his frustration this way:

On Facebook, most people are using their real names, but on Twitter, most of the usernames are not real, and we receive many critical comments from those anonymous users. Most of them are netouyo who spread false rumors like ‘our group is part of some political party (i.e., the Communist Party) or ‘we are associated with China.’ But if you do any activism (in Japan), there are always people who will criticise you. In the first place, it is abuse, not criticism. Honestly speaking, we want these anonymous users to give out their real names and show their real faces (like we do).

Anonymity allows the netouyo to create lies, spread rumors, and harass SEALDs members with little consequence or accountability. The rumors, lies, and aspersions are intended to sow doubt about the activists’ motivations and arguments without engaging in any serious policy-focused debate. Another SEALDs member explained the problem they faced with the netouyo this way:

Our group members know that what they (netouyo) are saying is false, so that’s fine, but when people from outside see that kind of information, when they search for it on the Internet, they would be like, ‘hmm?’ I don’t know how they could understand it, but I personally don’t want that kind of information to spread.

No matter how outrageous or patently false the netouyo’s claims became, the student activists still recognised that these lies complicated their message.

Lessons learned

The protest came to a head on September 19, 2015, when the Abe Administration passed its proposed security legislation despite widespread public criticism. SEALDs also disbanded around the same time, as they had always intended. Many of the members have since graduated from university and gone in various directions by getting jobs, going to graduate school, and involving themselves in grassroots political issues.

One of the lessons that SEALDs members learned during their student activism period was the added burden that female activists face when raising their voices in Japan. Part of the effect has been that several of the former SEALDs members joined the #MeToo movement (known as #WeToo in Japan) to apply their understanding of direct-action politics, and their experiences of harassment, by organising protests confronting gender discrimination.

In a recent interview with the Japan Times, Wakako Fukuda, one of the prominent female SEALDs members and frequent target of the netouyo, explained that women, in particular, need more support in dealing with harassment, online and elsewhere. She said,

People aren’t educated enough on this topic to know what harassment is and what it isn’t. And even when they know they’ve been harassed, it’s never easy to speak up, especially risking your career or place in your community.

Fukuda has detailed her experiences with harassment as an activist through her Twitter account and blog, fem tokyo. Through her reflexive narratives, she hopes it will better equip other women to contend with harassment.

One of the SEALDs student movement’s legacies is that many of the former student activists have transitioned towards pushing the conversation about gender equality and discrimination forward. Their voices ask an uncomfortable question about the added burden female activists face in Japan. They continue to question how much space and autonomy women have to engage in Japanese civil society.

Authors: Assistant Professor Robin O’Day, Satsuki Uno and Professor David Slater

Main image: Student Emergency Action for Liberal Democracy demonstration, August 23, 2015. Credit: Robin O’Day