Over recent decades, China’s economic boom and rapid urbanisation have contributed to increased numbers of Left-behind Children (LBC) and unaccompanied elderly in rural areas, whose closest family members have chosen to move to cities for better job opportunities.

There have been some particularly disturbing instances of what happens to those left behind. In November 2012, five LBC were found dead in a rubbish bin in Bijie, a prefecture-level city in the southwestern province of Guizhou. Reportedly, the children died of carbon monoxide poisoning after they lit a fire to protect themselves from the cold. Three years later, in the same city, four LBC from the same family committed suicide by drinking pesticide. Similarly, there have been many elderly suicide cases reported over the past decade which have been linked to isolation and loneliness. According to a World Health Organisation report, from 2009 to 2011, 44 percent of suicides in China were of those aged 65 or above, and 79 percent were among rural residents.

The Chinese central government has sought to address these problems by investing and resourcing a variety of schemes aimed at improving the well-being of rural residents, especially those who have been ‘left behind’. In particular, local governments are required to partner with non-state actors such as private companies, non-profit organisations or volunteers to provide social services for marginalised populations.

However, the approaches used to partner with non-state service providers have varied considerably, with significant implications for the quality of social services provided, and hence their ability to address the difficulties experiences by LBC and the elderly.

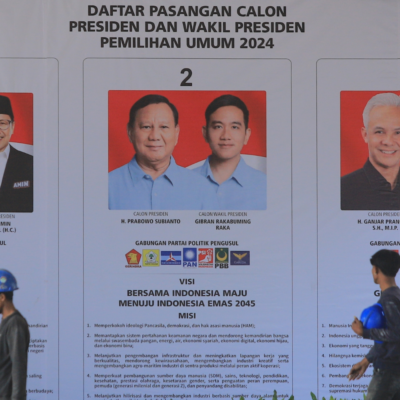

A rural nursing home in Anhui, China. March, 2018. Credit: Author.

I argue that the key determinant of success is the political will of local governments and their non-state partners to deliver quality services.

Social service delivery is usually regarded as a low priority by local governments because fewer performance credits are attached, compared to economic growth and social stability in a given tournament-like local government competition system. Therefore, traditional analytical frameworks focusing on the effect of performance management and incentive design on local governments’ behaviours are incapable of explaining the diverse local responses in China regarding social service delivery.

The concept of political will may offer another perspective for understanding governments’ willingness to pursue particular courses of action. Scholar Henry Mintzberg’s concept of political will refers to the willingness of individual actors to spend energy in pursuit of their goals. This concept can be applied to understand the willingness of states or governments to engage in particular activities or implement certain strategies. In a multi-actor policy process, political will can be understood as a shared understanding of a particular problem, a shared potentially effective policy solution, and a shared commitment to solving the identified problem.

This study defines political will as the extent to which local governments as policy implementers commit to the adoption of external partnerships as an effective means to deliver quality social services to rural marginalised groups. It takes into account not only the extent to which local governments are willing to initiate partnerships, but also their actions towards achieving effective partnerships.

Case study 1: A formal contract-based collaborative partnership

This partnership was a summer camp program that was co-delivered by the Communist Youth League (CYL) of County C and a local company based on a purchase-of-service contract in 2018. After the Chinese central government issued a national policy directive regarding LBC care in 2016, the leader of County C, who possessed a high level of education and formerly served as the deputy director of a municipal department in charge of rural development, gave the policy’s implementation high priority. He had the deputy head of the county government in charge of civil affairs establish a special working group, inviting relevant government departments, schools, communities, and potential service providers in the county to explore implementation plans together. The county leader also required relevant departments to view LBC care as a long-term responsibility and to innovate ways of service delivery. As an official stated, ‘the leader emphasised that he did not want to see […] outdated plans.’ The county leader prioritised achieving long-term local development goals and encouraged the use of innovative strategies to do so. Additionally, the policy implementation received financial support. From 2017 to 2018, the county government allocated 300,000 yuan (approximately US$43,363) from the county budget as a special fund for supporting LBC care and requested an additional 300,000 yuan from the higher-level government as supplemental funds. It is worth mentioning that this county was the only one in the province to allocate special funds to support LBC care projects, which can be attributed to the leaders’ concern for the welfare of rural vulnerable groups.

At a policy discussion meeting, the founder of a company involved in rural development and education proposed organising a summer camp for LBC. The company was experienced in such camps for children, and had a professional team and well-established facilities. The company also offered to conduct this special summer camp for LBC at a reduced rate. After considering the cost, project content, and the professional qualifications of the company, the county government decided to enter into a formal partnership with it. The contract stipulated that the company was responsible for organising three sessions of the program, each lasting seven days and involving 100 children. The county government paid 255,000 yuan for the contract.

Before the launch of the program, the county government worked with the township-level governments to select the target children and communicate with their parents or guardians. During the program, the government assigned a project commissioner to oversee the safety of the children.

The partnership between the government and the company in this case reflects joint commitment and equal cooperation of both parties. The company’s expertise in children’s education allowed it to play a leading role in program design, while the government played a role beyond that of a simple service purchaser. Through the combined efforts of both parties, the project received positive feedback from the service recipients and evolved into a signature initiative for enhancing the well-being of local residents.

Case study 2: Formal contract-based simple outsourcing

Under the guidance of national policies regarding the reform of elderly care, County Y initiated elderly care reform in 2018 by permitting private elderly care institutions to operate government-owned nursing homes. County Y was impoverished, but it was required to devise a policy response to the national directives. The county leader demonstrated task-oriented leadership by assigning related work and imposing strict deadlines for completion. ‘Our biggest task right now is eradicating poverty, so we firstly target the poorest elderly people and get them into nursing homes, while at the same time, we need to find companies willing to take over the nursing homes in a very short period of time,’ explained one official.

Due to insufficient financial resources, the county government decided to use funds that were previously directly distributed to a very vulnerable group in rural communities known as the ‘five guarantee elderly’ who have no work capacity or independent source of income (to whom the government provides five basic needs including food, clothing, housing, education, and burial expenses). The funds usually allocated directly to the ‘five guarantees elderly’ would be used to pay companies willing to take over the operation of nursing homes for them. Following a low-cost bidding process, the county government signed a contract with an elderly care company.

Under the contract, the company was paid 1,290 yuan, approximately US$186, per elderly person per month to provide full-day care. In 2018, I visited a nursing home operated by the company. There were 35 ‘five-guarantee elderly’ living in a poorly equipped three-floor village house, with two residents in each room. The nursing home provided the residents with three meals a day and other basic care. There was an open space on the ground floor where the residents could socialise and exercise. The company did not employ professional nursing staff, but instead hired two workers with domestic work experience from the local community, who were responsible for nursing, cooking, and cleaning. They were unable to provide professional medical care and support to the residents.

Despite the county government’s formal cooperation with the company, this simple service outsourcing reflects the county government’s lower political will to provide high-quality services to marginalised groups compared to Case Study 1. County government agencies were only concerned with completing short-term tasks and lacked the willingness to provide all the basic needs of rural elderly people including essential medical support and a decent living environment, nor did they participate in any way in service provision, as did the government of County C. In order to accomplish the task of reforming aged care services, the government of County Y did not make an effort to search for qualified service providers during the preliminary stages. The government also failed to monitor the quality of the services provided by the company, which contributed to the poor quality of the services.

Case study 3: An informal collaborative partnership

Unlike the government of County C, the government of County J was unable to allocate any special funds to support the implementation LBC care due to local financial constraints. In 2017, the county leader proposed a community-based solution. The county leader had previously worked in a developed district, where he was a senior social welfare officer, and placed a high value on non-state-led social innovation.

The county government reached out to a small local volunteer group of university students who, since 2015, had provided after-school education services for LBC in a local village. This group was not registered as a formal volunteer organisation but had worked closely with the village committee for two years and received widespread respect from local residents. The county government proposed that the group complete formal registration and expand its size and scope of services. However, the group’s leader stated that it would be difficult for them to recruit more local volunteers. In response, the county government decided to launch a countywide volunteer campaign for LBC care and moblised employees of the state system to volunteer. By mid-2018, the team had expanded from initially serving in one village with three volunteers to organising over 100 volunteers in five communities. Through the combined efforts of the county government and the volunteer group, the project has continued and served over 500 children to the present day.

Case study 4: Informal simple cooperation

In 2018, County S was a nationally-defined impoverished county and poverty alleviation was the top priority of the county leader. ‘In the past two years, we have devoted almost all of our energy to poverty alleviation. It’s not that caring for left-behind children and the elderly is unimportant; we just don’t have the time or resources to devote to it,’ said a township government official.

The county received some assistance from higher-level governments due to its status as a nationally-defined impoverished county. For example, from 2015 to 2017, the provincial government purchased professional services from a social work agency to support rural children in County S. At the end of 2017, when the project funded by the provincial government ended, the social work agency expressed its intention to continue providing services in the county. The county government was unable to purchase the agency’s services due to budgetary constraints, but in response to national policies on LBC care, officials from the county discussed feasible options with the agency through personal connection.

Similar to Case 3, the social work agency continued to provide services through volunteer recruitment. Without financial support, the organisation did not hire staff but instead recruited a local rural school teacher as the principal volunteer to plan and organise relevant activities. In the summer of 2018, this agency collaborated with a university volunteer group to organise a seven-day LBC care program. Fifteen student volunteers visited County S and spent a week with 37 LBC at a local school, teaching various subjects and running sports activities. The social work agency intended to seek financial and other support from the county government to organise regular volunteer programs as did the agency in Case 3. However, the County S government did not respond to the request. ‘The government uses us rather than genuinely supporting us. When they need to report their work to their seniors, they come to us for materials they can use as their work results. However, it’s difficult to solicit their support if we are not needed,’ said the principal volunteer.

This case demonstrates the government’s very low political will to provide LBC with high-quality services, and its cooperation with the social work agency was limited to the completion of work tasks. Due to a lack of financial and institutional support, the social work agency reportedly held only one event in 2018 before disbanding.

Conclusions and policy implications

These case studies indicate the importance of local governments’ political will when forming partnerships with non-state service providers. Although such partnerships can be an effective method for providing social services particularly in areas with limited resources, not all local governments have the political will to embrace this strategy.

Formal collaborative paid partnerships may produce the best service delivery because contracts clearly define the roles and responsibilities of each party. They may also mean that both parties can negotiate on an equal footing, contribute jointly, and supervise each other, resulting in the best possible outcomes.

However, a government’s ability to purchase services does not necessarily result in effective partnerships and the delivery of high-quality services. The level of political will of local leadership can influence how much effort related government departments invest in managing and cooperating with service providers. Local governments led by development-oriented leaders who prioritise people’s livelihood development are more willing to provide high-quality services in collaboration with external providers. In contrast, task-oriented leadership can result in local governments handling cooperation perfunctorily, thereby diminishing the quality of service provision.

Informal partnerships are a common strategy if a local government lacks the financial resources to enter into a formal paid partnership. In this context, the attitudes of local leaders towards the welfare and wellbeing of the rural marginalised, the demand for government funding by non-state service providers, and their service delivery capacity will impact the formation of their partnerships. Informal partnerships require more government engagement in order to deliver positive outcomes.

Governments can successfully save money and provide needed services by recruiting volunteers as service providers if they show the necessary political will. Under development-oriented leadership, local governments place greater emphasis on the value of volunteers and support the growth of local volunteering—leading to high quality service provision. In contrast, under task-oriented leadership, local governments view volunteerism as a tool for completing short term goals which may undermine the quality of service provision.

Underdeveloped rural areas require development-oriented leadership. Given that comprehensive reform of public service recruitment and personnel evaluation will require long-term change across many levels of government and agencies, a possible short-term solution would be to introduce continuing professional education for rural local leaders and officials. I found that many local leaders and key officials in underdeveloped regions lacked the knowledge and experience necessary to collaborate with non-state service providers. Continuing education and training could help resolve this issue.

Main image: Elderly Chinese women. Credit: Jordan/Flickr.