This article argues that the systematic persecution of the Ahmadi community in Pakistan is not simply a result of societal prejudice but is rooted in the deliberate state-sponsored integration of Islamist groups and ideology into politics, law, bureaucracy, education, and public discourse since the late 1960s.

This trend has been reinforced by transnational influences, the rise of guerrilla warfare in the region, and the concomitant militarisation of Pakistani society. The historical context of this narrative is the emergence of Islamist movements in India under British rule; their involvement in mainstream politics before and after partition; the Pakistani state’s attempt to formulate its version of Muslim nationalism by courting Islamist groups and sidelining leftist and ethnic politics; and the subsequent proliferation of increasingly radical interpretations of Islamic law and principles.

A brief background of the Ahmadi community in Pakistan: 1889-1965

The Ahmadiyya community was formed in 1889 in Indian Punjab by the followers of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, who claimed to be the promised messiah and in later years, a prophet. Concurrently, between 1857 and 1947, British India also witnessed three other Islamist movements: Deobandi, Barelvi, and Jamaat-e-Islami.

Based in urban areas of Northern India and belonging to the Sunni sect, all these movements were united by their aim to protect Islamic institutions and practices from the challenges posed by colonial rule. However, they disagreed on the legitimate sources for Islamic law and the authenticity of rituals associated with Sufi shrines, with each movement claiming to be the only authentic bearer of faith.

After Pakistan became independent from the British in 1947, the Ahmadis, Barelvis, Jamaat-e-Islami and Majlis-e-Ahrar, a breakaway faction of the Deobandi movement, moved to establish their structures in the new country. But all Islamist groups remained marginalised from constitutional discussions. After the military coup of 1958, Islamist parties retreated even further into political irrelevance, until the crisis of 1965-1971 ushered in an improvement of their fortunes.

The turning point: 1965-1977

In 1965, the military regime in Pakistan initiated a war with India and the subsequent lack of a decisive victory led to large-scale protests led by students, workers, and disaffected ethnic groups. Three years of unrest led to a change of top leaders and forced the new general to hold the first national elections based on universal franchise in 1970. The victory of a self-declared socialist party in the western part of Pakistan and that of a nationalist party in the eastern part deepened the crisis. As unrest in the east turned into an insurgency, which a military operation failed to quell, India intervened on behalf of the secessionist movement. This ended in 1971 with the creation of Bangladesh in the eastern wing, and the end of direct military rule in the rest of Pakistan.

The dominance of class and ethnic disaffection rather than religious issues throughout the crisis brought the Islamists closer to the military elites in common opposition to leftist or secessionist politics. To varying degrees, Islamist groups started providing their ideological and political support, and motivated vigilantes to join the military in return for patronage, funds, weapons, prestige, and exposure on national media.

The mutually beneficial military-Islamist relationship flourished after 1965 and became militarised because of international factors. After 1973, Saudi Arabia sought to convert its enormous oil wealth into ideological influence in the Muslim world by funding organisations and initiatives against leftist forces. The United States also supported radical Islam and Pakistan would become the prime beneficiary of this joint campaign after 1979.

The first manifestation of the Islamists’ backing by both Pakistan’s military and Saudi Arabia was the anti-Ahmadi movement of 1974. The civilian government had passed the first consensus-based constitution representing all political parties in 1973. Within a year, however, Saudi organisation Anjuman Rabita al-‘Alam-i-Islami organised a conference in Mecca, attended by influential Pakistani politician and Islamic scholar Maulana Noorani , which passed a resolution against Ahmadis, in addition to a resolution against socialism. In June 1974, 18 religious and political parties formed the All-Pakistan Khatm-i-Nabuwwat Action Committee (APKNAC- Al-Pakistan Committee for Finality of Prophethood). They made numerous demands, including that Ahmadis be declared non-Muslims and be removed from key government posts. The broad and well-coordinated alliance led by Jamaat-e-Islami students soon engulfed all the major cities of Punjab with violent demonstrations and strikes. The military tacitly backed this movement because the Ahmadis had collectively supported the leftist party in the 1970 elections.

Pakistan’s government unsuccessfully tried to weather the storm with complaints of an international conspiracy. In September 1974, the National Assembly amended the Constitution to formally declare Ahmadis as non-Muslims and made it mandatory for individuals to declare their religion on their passports. Saudi Arabia then financed several international visits by Pakistani leaders to propagate the initiative. In a reversal of the 1953 riots, the military this time backed the street muscle of Islamist groups against the political regime. The campaign resulted in a large-scale purging of Ahmadis from the higher echelons of the bureaucracy and academic institutions. It also laid the grounds for the remarkably coordinated and successful movement that would oust the civilian government in a military coup in 1977 in the name of Nizam-e-Mustafa, or an Islamic system.

The Islamic Republic of fear after 1977

The military regime, led by Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, and backed by all Islamist parties, started the country down an irreversible road to its stated goal of an Islamic state. This process was bolstered in no small way by the steady flow of US and Saudi cash and logistical support to fight both Soviet socialism and Iranian Shi’ism in Afghanistan and Pakistan after 1979. For the first time, Islamist groups in Pakistan got easy access to sophisticated weapons and vehicles, international exposure, interaction with militants from the Middle East, and first-hand experience in military combat. The foundations of the Islamisation project initiated during the military rule of 1977-88 were so strong that it continued in the brief democratic interlude of 1988-1999, and accelerated after the coup of 1999. The US invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 and Pakistan’s complicated relationship with regional and local Taliban groups gave ever more violent dimensions to this process. Four aspects of this Islamisation project are crucial.

First were a series of legal Islamic measures. These included ordinances between 1979 and 1981 related to moral policing, which imposed criminal penalties including public floggings and arrests for gambling, drinking, and attending nightclubs, and eating in public during the month of Ramadan. The Hudood Ordinances of 1979 prescribed punishments such as stoning, beheading, and amputation for crimes related to sex and property. Between 1980 and 1984, three ordinances amended the existing anti-blasphemy law to prescribed fines and life imprisonment for defiling the Prophet or his family, damaging or desecrating the Quran, and specifically for Ahmadis ‘posing’ as Muslims. In 1985, the Constitution was amended to introduce separate electorates for all non-Muslims, effectively disenfranchising Christians and Ahmadis. In later decades, the legal system became more Islamised as courts not only upheld most of the Zia-era regulations and amendments, but imposed harsher sentences in multiple cases, especially by making the death sentence mandatory for blasphemy.

Second, the state backed both organised and vigilante violence by Islamist groups. Some JI militias had already supported the military operation against secessionist groups in East Pakistan. After 1977, their foot soldiers were given free rein to kill, harass, and intimidate leftist students and organisations, labour leaders, intellectuals, journalists, professional women, and lawyers. In return for targeting political dissidents, the militias have over time been given the license to target non-Muslims or even ‘immoral’ Muslims in the name of defending Islamic honour. Both the perpetrators and targets of such attacks have expanded over time, with Barelvis joining the former ranks, and artists the latter.

Third, the Shias of Pakistan were redefined as a minority. After 1979, both Saudi Arabia and Iran had flooded Pakistan with radical literature of their respective sectarian beliefs. Further, since Zia’s multiple Islamisation measures had a strong Saudi stamp, they led to large-scale demonstrations during the martial law period, earning the regime’s hostility. In this tense context, the Saudi monarchy obtained an edict from leading Deobandi scholars in India declaring Shias as non-Muslims. Some Deobandi scholars in Pakistan followed suit, leading to the emergence of militant Sunni organisations in Punjab demanding the constitutional excommunication of Shias in the same vein as Ahmadis. While the state has not yet acquiesced to this demand, Pakistan did witness the emergence of Deobandi militant organisations dedicated to targeting the Shias in the mid-1980s, starting with the Anjuman Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (ASSP). The extent of their aggressiveness led the Shia groups to respond with their own sectarian political and militant organisations for the first time in the region’s history.

The 1990s were defined by a steady trend of violence perpetrated by Shia and Sunni organisations targeting key leaders and religious gatherings. By the late 1990s, however, Sunnis had decisively gained the upper hand for two interrelated reasons. First, the vigilante groups tasked with targeting real or perceived internal enemies of the military were all Sunni. Second, the Pakistani military started two simultaneous fronts of guerrilla warfare in the 1990s: the Saudi-financed and influenced Lashkar-e-Tayyaba movement in Indian Kashmir, and the Afghan Taliban, who represent a particularly extreme version of Deobandi thought. These two operations reinforced and supported each other in terms of recruitment, resources, training, finance, and state-backing, militarising both the country and the region, and leaving Shia organisations far behind.

The Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan insurgency since 2002 reflects an expansion of already existing ideology and infrastructure through the ambitious use of large-scale or suicide bombings. The Taliban attacked the usual suspects (leftist students, secular or ethnic politicians, intellectuals, journalists, Shias, Christians and Ahmadis) more dramatically and fatally, and added to the list state personnel, Sufi shrines, artists, and even Islamist political parties or groups they considered to be too moderate.

Over time however, state support, Saudi financing, and a symbiotic relationship with Afghan militant groups resulted in the prevalence of Sunni groups. Their dominance was further strengthened by Salafi-dominated Kashmiri militancy in the 1990s, and rise of the Afghan Taliban. . The scope of localised militancy in Pakistan exploded after the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) insurgency in 2002 and their use of suicide bombings. While the key targets of the TTP have been state personnel, secular political parties, and Sufi shrines, they have also attacked rival Sunni groups, Shias, Ahmadis, and Christians on an unprecedented scale.

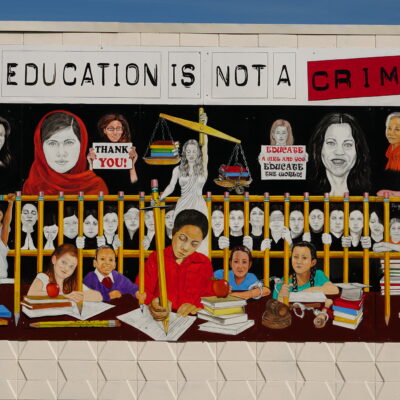

Fourth, in the 1980s the Pakistani military undertook a systematic rewriting of the educational curriculum, history, and national discourse of Pakistan in Islamic terms, work that was sustained by later political regimes. As a combined product of these four processes, there has been a steady expansion of a network of Islamist educational institutions, think tanks, publications, civic organisations, professional associations, and rejuvenation of some older organisations such as Majlis-e-Ahrar. The demonisation of non-Muslims, legitimisation of violence for a perfect Islamic society, more radical interpretations of religious concepts, and conspiracy theories have moved from obscure religious magazines and gatherings to the front pages of newspapers, textbooks, court decisions, and prime time talk shows on television and online. This state-supported, but mostly autonomous, infrastructure has expanded and consolidated steadily over five decades. Even if the militant groups can be temporarily neutralised by state policy, the radicalisation of the national discourse, culture, judiciary, and even the bureaucracy is now entrenched.

Profile and responses of religious minorities

While Ahmadis, Christians, and Shias have all been affected by the Islamisation and militarisation of Pakistan, the mechanisms and scale of violence, and the responses of each community have been different, based on their historical and demographic profiles.

The Shias are 15-20 percent of the Pakistani population, historically over-represented in the landed elites and educated classes. They have been attacked by the Anjuman Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (ASSP) and its offshoots, and later the Pakistani Taliban on an ambitious and systematic scale through targeted assassinations and large-scale bombings. After losing the militant struggle in the 1990s, they have responded by forming grassroot civil and professional organisations, insisting on observing their rituals in public, and developing an alternative discourse in print and online. They also receive mostly sympathetic treatment from broader society, aside from the militant Deobandi organisations.

Christians constitute 1.31 percent of the total Pakistani population and number approximately 2.6 million. Being mostly converts from outcastes, they occupy the lowest socio-economic ladder. Large numbers are unemployed, or work as janitors, secretaries, or bonded workers at brick kilns. They have responded by retreating further into their ghettos, adopting Muslim names, paying protection rent to local bullies, or sometimes converting to Islam.

The total Ahmadi population is officially recorded as 191, 737 (0.09 percent of the total population), which is likely to be an underestimate, as some members are afraid to officially declare their faith. The total worldwide figure cited by community members is around one million, including all the diasporas and new converts.

Ahmadis and Christians continue to experience mob attacks and targeted killings, often after accusations of blasphemy. The legal system and state machinery have made it acceptable for any individual or group to attack minorities in the name of protecting the ‘honour’ of Islam. Allegations of blasphemy can be used without any evidence to settle personal scores, for intimidation, to get a coveted job or business, end a dispute over property, get out of an outstanding debt and many other situations. Regardless of the intent, the end result is either death by the mob or the police, or decades spent in prison.

Two factors set Ahmadis apart from Christians. First, anti-Ahmadi discourse has gradually become more militant, shifting from being regarded as ‘non-Muslims’ to being ‘apostates’, which makes them liable to be killed under some religious interpretations. Anti-Shia diatribes are restricted to the margins of religious discourse, and Christians are not considered important enough. But there are influential specifically anti-Ahmadi organisations, publications, regular events, and mainstream literature. Being anti-Ahmadi enables all Islamic groups and sects to subsume their differences and speak with one voice. Anti-Ahmadi beliefs are also proudly expressed by non-religious Muslims.

Second, while Ahmadis have given in to intimidation within Pakistan by abandoning communal gatherings, their socio-economic status has enabled them to emigrate in large numbers. Since the community head moved to London in 1984 after death threats, Ahmadis have recreated a well-organised and centralised diaspora community headquartered in England, with their own satellite television channel. They also have an organised presence in Germany, Canada, the US, and Australia. The challenge for these diaspora communities is to maintain their goodwill in the West and also help their members who lack the resources to leave Pakistan and must live in perpetual fear for their lives.

Conclusion

Ahmadis are numerically an insignificant group within Pakistan, but their trajectory is reflective of the broader issues that now plague the country in its pursuit of national unity and regional influence. As the Pakistani military has patronised, recruited, and deployed Islamist groups and sought international donors to fight a range of internal and external enemies, it has irreversibly changed its constitutional, legal, and intellectual structure, eliminated all secular political voices, and created its own biggest challenge. The ongoing Taliban insurgency has claimed more military and civilian lives than all wars with India combined, and the Taliban have been the hardest to neutralise precisely because of the decades spent by the state and society supporting and defending Islamist violence. The Ahmadi community might be able to respond to its challenges, but it is questionable if Pakistan can find an alternative unifying force and reverse over five decades of Islamisation and militarisation.

Image: Grave of Prof. Dr. Abdus Salam (1926-1996) in Rabwah. In the English inscription the phrase “the first Muslim Nobel laureate” the word “Muslim” has been erased. Credit: Scourgeofgod/Wiki Commons.