More than 10 years after the genocide of Ezidi Kurds, a religious minority community in northern Iraq, thousands of Ezidi men and boys remain missing and approximately 3,000 women and girls continue to suffer rape and other violence at the hands of the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant (ISIL).

The attack by ISIL on Ezidi Kurds in June 2014 marked the beginning of a horrific wave of mass killings and violence carried out in the name of Islam. The stigmatisation of this minority group as infidels has resulted in their mass murder and the enslavement of women. This article explores how the rights of Ezidis were violated and highlights atrocities committed by the Islamic State against them. To understand the roots of ISIL’ violence against the Ezidis, it is essential to examine the key theological differences between Islam and the Ezidi faith, which the Islamic State invoked to justify its hostility and to frame the elimination of this group as a religious duty. I also explore how the international community responded by condemning the violence against Ezidis and formally recognising it as genocide.

Ezidism

The Ezidi religion (also known as Yezidism or Ezidism) is one of the oldest monotheistic religions. Throughout history, Ezidism has been misunderstood by both some Western and Islamic scholars. Karl May, a German orientalist, referred to them as ‘Devil Worshipers’ in his Durchs Wilde Kurdistan (1892). Others have considered Ezidism a branch of Islam or associated it with Yezid ibn Mu‘awiya (647-683), the second caliph of the Umayyad dynasty, who was responsible for the murder of Hussein ibn Ali, the third imam of Shi’a Muslims. This association of Ezidis with Yezid was particularly emphasised during the regime of former President of Iraq Saddam Hussein (1979-2003) to stigmatise the group and increase hostility between Shi’a Muslims and Ezidi Kurds.

Prominent anthropologist, the late Fuad Khuri, states that Ezidis emerged after the rise of Islam and combined Sufi elements, the Sabaean doctrine of reincarnation and Babylonian funeral rituals. Religious historian Solomon Negosian agrees with Khuri and holds the view that Ezidism is an Islamic adaptation incorporating Jewish, Zoroastrian, Christian and Manichaean elements to form a new religion. However, Ezidis distance themselves from any association with the Islamic faith, asserting that their religion predates even Judaism and traces its origins back to the time of the ancient Assyrians and Babylonians.

Theological difference: The roots of religious allegations

Most Ezidis identify as Kurds, while a minority associate the term ‘Kurd’ specifically with Muslims in the region and instead claim a distinct ethnic identity. While many Kurds were forcibly converted to Islam in the 7th century, Ezidis resisted the Arab-Islamic expansion and remained loyal to their faith. Since then, they have faced numerous attacks from Islamic authorities and groups, enduring constant threats and persecution throughout history.

Ezidism does not have an early tradition of writing, which can be a challenge for researchers. Written religious texts only appeared in the 12th century, with figures such as Shaykh Adi bin Musafir (1074-1162) and Hassan bin Adi (d. 1254) the great nephew of bin Musafir who are both known as Ezidi reformers.

Bin Musafir, the author of Kitab-i-Jelwa (The Book of Revelation) in Kurdish, was originally a Muslim mystic who studied under Imam Ghazali, one of the most influential scholars in Islamic history, in Baghdad. After completing his studies and performing pilgrimage to Makka he resided in the valley of Lalish, an area inhabited by Ezidis in Iraqi Kurdistan. He converted to Ezidism after seeing the Peacock Angel (Malak Taus) (one of the central figures in the Ezidi religion) in a mystic experience and spent the rest of his life in Lalish, the holiest Ezidi site.

Bin Adi is the author of the second religious text, Meshef-i-Rash (The Black Book), which outlines the Ezidi worldview and theological doctrines. These include the creation of the world, the transgressions of Adam (the name given to the first human being created by God in Judaism, Islam and Christianity), reincarnation, and the roles of seven angels, with particular emphasis on the Peacock Angel’s responsibility for overseeing worldly affairs. This text establishes a clear distinction between the Ezidi worldview and that of Islam. It rejects the association of evil with Satan and denies the objective reality of evil —since there is no Satan, evil should be understood as the product of human actions. It also states that God created women 100 years after Adam’s transgression and God (since He/She is the most merciful) forgave the angel who deceived Adam to disobey God ‘Meshef-i-Rash’. Like Christians, the Ezidis baptize their children using water from the sacred valley of Lalish. They do not have a designated place for prayer, but they pray three times daily, facing the position of the sun in the sky.

The theological differences between the Islamic worldview and that of Ezidism, particularly regarding the doctrine of creation and the origins of evil, have fuelled hostility toward Ezidis by various Islamic groups. Additionally, Ezidism, unlike Judaism and Christianity, is not recognised as a revealed faith with sacred texts and its name is not mentioned in the Qur’an, so it is branded heretical. As promoted by the Islamic State, jizyah (a tax historically paid by non-Muslims, such as Jews and Christians, under Islamic rule) is not levied on Ezidi followers; instead, they are given the ‘choice’ to convert, be enslaved, or face death. For ISIL, the act of killing Ezidis serves a dual purpose: it is both a religious obligation to combat the enemies of Islam; and Muslims killed in this pursuit are considered martyrs and promised a reward by God.

In June 2014, ISIL seized control of a vast area of Iraq, including Mosul, the country’s second largest city, and the Sinjar (Shingal) district, home to a large population of Ezidis. On August 3, 2014, the Islamic State’s fighters launched an attack on Sinjar, marking the beginning of the massacre of Ezidis, an historically very significant attack even in the context of their long-standing persecution. A large portion of the Ezidi population fled their homes and sought refuge on Mount Sinjar, where many perished from hunger and thirst. A recent United Nations report states that ‘ISIL committed genocide as well as multiple crimes against humanity and war crimes through mass executions, forced religious conversions to Islam, enslavement and widespread sexual violence against women and girls’. Ezidi shrines and religious symbols were destroyed, and many Ezidis were captured or killed. The captured men and boys were separated from women and children. The men were compelled to choose between conversion and death. Converts were treated as slaves and forced to work for ISIL. Those who refused to convert were publicly executed. Boys were taken at the age of seven and sent to training centres, taught Arabic, indoctrinated and trained to become fighters and suicide bombers.

The Islamic State’s campaign against the Ezidis proved effective in part because it was framed in theological terms, encouraging many Sunni Arab Muslims who had once lived peacefully alongside the Ezidis as neighbours to participate in the killing and enslavement of Ezidi women. ISIL’s onslaught was a brutal and a well-planned mass killing, reinforced by a theological justification that it advocated and promoted. Many of the survivors migrated to European countries and Australia. A significant portion of the Ezidi population currently resides in refugee camps in the Kurdistan region of Iraq.

The sexual enslavement of Ezidi women

ISIL permitted the abduction of Ezidi women and forced them to slavery as Sibaya, a term referring to young girls bought and sold as sex slaves in accordance with Islamic law. It is reported that girls from the age nine were taken away from their mothers and sold as slaves in the cities controlled by ISIL. More than 5,000 Ezidi girls were either sold as sex slaves or given as gifts to the leaders of ISIL.

Nadia Murad, an Ezidi girl whose family members were murdered and who was abducted by ISIL before eventually escaping, has shared a disturbing account of the suffering endured by Ezidi girls in captivity, drawn from her own experience. In the foreword of Murad’s book, Amal Clooney, a high profile international human rights lawyer writes, ‘She [Nadia] was forced to pray, forced to dress up and put make up on in preparation for rape, and one night was brutally abused by a group of men until she was unconscious.’ Murad recounts that ISIL fighters extinguished cigarettes on their bodies: ‘Nafah [a fighter] pushed the lit cigarette on my shoulder…The smell of burned fabric and skin was horrible, but I tried not to scream in pain. Screaming only got you into more trouble.’ The slave market for Ezidi girls was usually opened at night and Murad described it as ‘…like the scene of an explosion. We moaned as though wounded, doubling over and vomiting on the floor, but none of it stopped the militants…. Those of us who knew Arabic begged in Arabic, and the girls who knew only Kurdish screamed as load as they could, but the men reacted to our panic as if we were whining children, annoying but not worth acknowledging. [ …] They gravitated toward the most beautiful girls first, asking “How old are you?” and examining their hair and mouths. “They are virgins, right?” they asked a guard, who nodded and said, “Of course!” like a shopkeeper taking pride in his product.’

On 20 October 2017, the city of al-Raqqa, the capital of the Islamic State, was liberated by the Syrian Democratic Forces, an Arab-Kurdish coalition. Since then, the Kurdistan Regional Government of Iraq (KRG) has been actively working with international organisations to locate and rescue the Ezidi girls who were captured. The KRG has successfully rescued 3,585 women and children and has also provided financial assistance in the form of a monthly allowance to the rescued girls, helping them support themselves. However, the fate of thousands of them remains unknown.

The international community’s response to the Ezidi genocide

The mass killing of Ezidis has been recognised as a genocide as defined in the Genocide Convention of 9 December 1948 by many parts of the international community. The United Nations established the UNITAD (the Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Crimes Committed by Da‘esh/ISIL) to initiate investigations into these crimes. Its investigators collected evidence to substantiate the crimes classified as genocide and the UN has concluded that the Islamic State attempted to erase the Ezidis’ religious identity through violence and coercion.

Many nations, including Germany, France and Australia, have also officially recognised the violence against Ezidis as genocide and called for the leaders of ISIL to be brought to justice and held accountable. The recognition of these crimes as genocide holds deep significance for the Ezidi community, as it represents a formal acknowledgment by the international community of their suffering. However, no Islamic State leader has yet been officially charged or brought to justice.

Conclusion

The Islamic State and other jihadist groups justified their violence and religious intolerance through their interpretation of Qur’anic verses concerning the relationship between Muslims and non-Muslims, including those that call for fighting non-Muslims.

To effectively combat such violence, it is crucial to promote an Islamic theology that challenges the ideological foundations of groups such as ISIL, one that emphasises tolerance, peaceful coexistence, and the protection of religious minorities. Without such theology, religious violence against minorities endures, and social harmony and cohesion in the Muslim world continues to be undermined.

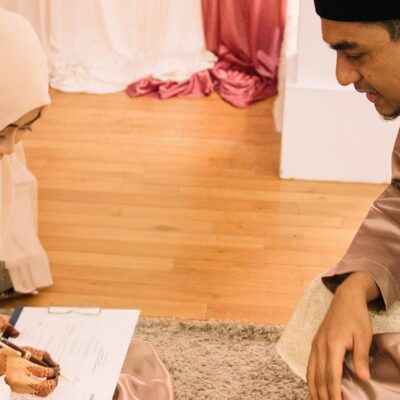

Main image: Ezidis celebrating Ezidi New Year in April 2018 at Lalish. Credit: Levi Clancy/WikiCommons.