It is no exaggeration that the bilateral relationship between Australia and Japan is one of the great success stories of Australian post-war diplomacy. First and foremost, Japan is arguably the most important as well as one of the longest bilateral relationships Australia has had with any Asian country. In overall terms, the relationship can be summarised as close, mostly trouble free and highly profitable. As a result, Japan has had a profound impact on overall Australian policy making. Initially based on massive volumes of trade with the signing of the 1957 Agreement on Commerce, the relationship has developed into a mature and multi-faceted partnership that retains extensive commercial links and has an increasing focus on security and regional cooperation.

Moreover, both countries are dependent on the United States for security and strongly support free trade, the rule of law, democracy and human rights. These commonalities have led to substantial coordination between Tokyo and Canberra over the past five decades on a diverse range of areas including non-traditional security and economic-security issues such as free trade agreements, aid and development projects and combatting climate change and piracy.

Tensions over whaling and a poorly handled ‘done submarine deal’ in 2016 that was won by a French tender non-withstanding, the bilateral relationship between Australia and Japan has gone from strength to strength in recent years. A major reason for this has been shared concerns about China claiming disputed islands in the South China Sea and direct challenge to the United States in the Indo Pacific. Despite this, the Canberra-Tokyo connection receives less attention in Australia than it deserves. Understandably, our troubled relationship with China and political gridlock in Washington and the implications for Australia, dominate international political headlines and distract from reporting on the significance of developments in the Australia-Japan relationship.

In many respects the lack of coverage is not surprising given the durability of ties between Australia and Japan and the extent of networking at the government and subnational level. Over the past 60 years, external factors and domestic priorities in both countries have led to ‘highs’ and ‘periods of inaction’ in the management of bilateral relations and a tendency towards complacency. The shared desire by both countries that the United States remain a significant power in the Indo Pacific to balance China, however, has given the Australia-Japan relationship a huge fillip in recent years and led to a new ‘high’ in bilateral ties based on mutual security concerns.

Security ties are locked in

Consultation and cooperation on politico-security matters between Australia and Japan started from a low base and was well underway before China emerged as a threat to the status quo in the Indo Pacific. Ad hoc security consultation began in the early 1960s and increased incrementally over subsequent decades. By the 1990s there was an exchange of defence attaches and Australia also supported Japanese involvement in United Nations Peace Keeping operations in Cambodia (1992-93) and East Timor (2002). A critical factor in fast-tracking already rapidily developing political/security ties, however, was the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11, 2001 (‘9/11’). In many respects security consultation was the missing piece in an already close bilateral relationship based on trade complementarity and strong political ties. A series of bilateral ties, memoranda and agreements ensued culminating in the Joint Declaration on Security Co-operation (JDSC) in 2007. Notably, Australia became only the second country (after the United States) to sign a security agreement with Japan in the post-war period. The security agreement—which has provided a platform for expanded security ties, including annual consultation at the ministerial level (‘2+2 Talks’ among defence and foreign affairs ministers) and bolstering of military ties—is not a treaty in the conventional sense. For example, there is no provision for military support in the case of attack. Instead, the focus of the agreement is non-traditional security such as dealing with a refugee crisis, environmental disasters and humanitarian and development issues. The arrangement suits both countries and is necessary for Japan due to Article Nine of the Japanese Constitution that limits the role of the Self Defence Forces.

Interlinked has been the development of trilateral engagement with the United States known as Trilateral Security Dialogue (TSD). First raised as a concept by then Australian Foreign Affairs Minister Alexander Downer in July 2001 to combat terrorism in the region and consolidate existing security ties, the development of annual TSD talks since 2002 have allowed the United States, Australia and Japan to work closely and ensure increasing levels of interoperability between military forces through joint training and sharing of intelligence information. The process has allowed for the streamlining of military and intelligence communities in all three countries.

Regular security upgrades since the JDSC over the past 15 years have ensured close cooperation, frequent meetings and military training (including on Australian soil) between Australia and Japan. In November 2020, the relationship with Japan was upgraded to a ‘Special Strategic Partnership’. As the term implies, there is close cooperation, regular meetings and military training (including on Australian soil) on a previously unprecedented scale. As noted by Thomas Wilkins, bilateral cooperation through the ‘Special Strategic Partnership’ mechanism has now become entrenched as a ‘fixture’ of both Australian and Japanese foreign, economic and security policy. The signing of the Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA) on the 6th of January 2022, after several years of negotiations, has solidified these developments. The historic agreement allows for Australian and Japanese soldiers to act and operate together seamlessly. It is the first such agreement that Japan has signed with any country other than the United States.

China is now a major concern

Undoubtedly the prime motivator for upscaling security measures in recent years has been concerns about China as a direct competitor to United States leadership in the Indo Pacific. Now a superpower with global economic reach, China has transformed the global economy and established itself as a rival to the United States. Chinese assertiveness in the South and East China Seas and border clashes between Indian and Chinese soldiers moreover have galvanised support for increased cooperation by like-minded countries to balance China and to some extent restrain Chinese activities and influence in the Asia-Pacific region.

For Australia and Japan this has meant redoubling efforts in coordination with the United States to strongly promote the right of passage through the South China Sea and a Free and Open Indo Pacific framework (FOIP). As well, additional layers of security have been added to existing networks which have enriched the bilateral relationship, and which expand on both bilateral and multilateral security initiatives. The premier example is the expansion of TSD to include India in the Quadrilateral security dialogue (Quad) between Australia, Japan, India and the US. The Quad was originally created in 2007 but collapsed in 2008, largely due to a desire not to offend China. The return of the Quad (Quad 2.0) in 2017 was in direct response to the rise of China as a direct competitor to the United States and as demonstrated with the recent Quad meeting in Melbourne the shared concerns of established order in the region unravelling.

Despite this, there has been some substantial differences in approach taken towards China by Australian and Japanese governments. Unlike Australia’s ever worsening relationship with China, Japan has been enjoying a thawing in political relations and a gradual improvement in diplomatic ties with China since 2014. Indeed this is despite the unresolved legacy of the Pacific War, territorial disputes over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands and Japan’s increasingly close ties with Washington. The heavy lifting in Tokyo has been part of a concerted diplomatic effort by Japan that has transformed a poor relationship with China into a sound one that is pragmatic and focused on communication with the Chinese leadership. Notably even with restrictions due to COVID-19 and Japan’s support for the Quad and a ‘Free and Open Indo Pacific’ framework, high-level face-to-face talks at the ministerial level have led to agreements between China and Japan on upholding and strengthening rules-based multilateral trade through a three-way trade deal with South Korea and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership which, when fully implemented, will be the largest free trade agreement in the world. A fundamental reason for Japan’s policy of engagement with China is the economic windfall of maintaining sound bilateral relations. It is a pragmatic approach that has reaped substantial rewards as last financial year China became Japan’s largest export market, replacing the US and accounting for 22.9 percent of Japan’s total exports.

Nonetheless, there has been increasing concern in Tokyo about China’s aggressive stance towards ongoing territorial disputes and threats of invasion of Taiwan over the past few years. A ‘hot’ war between China and Taiwan is a major source of concern for senior Japanese officials. This is not surprising given Taiwan’s proximity to Japanese territory and the fact that the US base in Okinawa would be used by US forces if defending Taiwan, thereby bringing Japan into the conflict. As noted by Deputy Prime Minister Taro Aso in testimony to the Diet in July 2021, such a scenario would threaten Japan’s survival.

The policy to oscillate between a conciliatory approach focused on commercial ties and economic cooperation and assertiveness in dealing with China was developed by then Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, like his short-term predecessor Yoshihide Suga, has maintained this approach and has also retained China hardliners in his cabinet, including Defence Minister Nobuo Kishi (Abe’s brother). Indeed, Kishida’s election victory with the loss of only 12 seats in early November 2021 means that the LDP/Komeito coalition retains a substantial majority in the Diet and thus also a mandate to push for higher defence spending (including doubling the defence budget to two percent of GDP) and a tougher military posture in light of China’s assertive position in the contested East China Sea. The fact that Kishida, who comes from a pro-China faction within the LDP, took these polices to the election and the relative success in the Diet reflects a hardening of resolve within the general population and political elite to be more assertive with China.

Hot topics for the Australia-Japan bilateral relationship in 2022

1. Using the Quad to promote peace

As well as developing stronger military ties, Quad 2.0 also offers non-traditional security opportunities that play to Australia and Japan’s strengths. Key examples include combatting the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change and assisting with critical technologies in the Indo Pacific. These policies establish a positive and constructive tone which sits comfortably with both countries’ regional diplomacy. Insofar as the focus on non-traditional security goes, Australia and Japan have been careful not to antagonise or inflame security tensions with China. Vaccine diplomacy is a clear priority during the pandemic and although there is competition with China over supplying vaccines, it nonetheless positions the Quad countries in a positive light. Climate change, moreover, is a good example of an area in which China is a cooperative player and not a competitor. Combined, the three initiatives are designed to construct an environment that is inclusive towards China and may persuade other states to shed their hesitancy towards the Quad.

2. China’s entry into the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership

China’s application to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) is another opportunity for Australia and Japan to be inclusive towards China. Originally constructed as a free trade grouping to counter China’s economic power, there is some concern that China’s entry into the CPTPP may alter the framework and policy direction of the organisation. Currently TPP members (including Australia and Japan) are scrutinising the application. Both countries want China to comply with CPTPP requirements for transparency and non-discrimination between foreign and domestic companies among other provisions. Australian officials are also adamant that China needs to end its trade embargoes on Australia and resume ministerial consultations. A potential source of tension in bilateral relations is the possibility of Japan supporting China’s inclusion and Australia not. Given Japan’s policy of economic engagement with China and the downward spiral in Australia’s relationship with Beijing, this is a conceivable scenario. The fact that Vietnam, with similar economic characteristics to China, is a member with special provisions also makes the possibility of China’s inclusion more feasible. Ideally, Tokyo and Canberra will be in alignment to support China’s membership push. It would showcase a more nuanced approach by Australia as part of a new approach to China that allows for both discord and cooperation. Such an approach will also support both countries’ desire to involve China in regional settings as part of a strategy of increased avenues for communication and norm setting.

3. Japan and AUKUS

Having stated that there is some incremental movement towards restoring relations with China, the Australia, United Kingdom and the United States security pact (AUKUS) established in secrecy and announced with some fanfare in September 2021, is a further layer of security dialogue designed to counter China’s influence in regional affairs. The main item so far from the initial meeting was the Australian decision to scrap a submarine deal with a French company and replace it with a nuclear-powered submarine with technology from both the UK and US. Japan has officially endorsed AUKUS, which is not surprising given that the pact re-iterates the US commitment to the region and brings in the UK as an active partner alongside Australia. Given the way in which the French submarine contract was terminated in such a brutal and clumsy manner however, Japanese officials will no doubt be relieved that their own submarine tender was unsuccessful in 2016.

AUKUS has met with a mixed response by countries in Southeast Asia concerned at being excluded from the process and the possibility of an arms race in the region. Efforts by Japan to support AUKUS and use its diplomatic skills and connections with elites to get countries on board would be a major contribution. As a close US ally and a member of the Quad and through its strong connections with countries in the region, it is logical to expect that Japan would act as a bridge between AUKUS and Southeast Asia. Specifically, it has been suggested that Japanese diplomats could assist with institutionalising communication and dialogue with like-minded countries in Southeast Asia.

Japanese officials however may be reluctant to do much for AUKUS in Southeast Asia. Initial responses in Tokyo by defence and security commentators have been to stress how AUKUS emphasises the Anglo-American alliance and a feeling of being excluded. Membership of AUKUS is possible in the future given that Japan has close security ties with the US and Australia and a relatively robust and long-standing bilateral defence relationship with the UK. A potential barrier, however, is that leaking confidential information to a third party has been a persistent problem in Japanese government and bureaucratic circles and this has been a barrier to Japan’s past aspirations to affiliate with the Five Eyes intelligence framework.

4. New directions: cooperation on climate change and zero emissions targets

Bilateral cooperation on strategies dealing with climate change and zero emissions targets are illustrative of new directions in the Australia-Japan partnership. Japan’s pledge of a 46 percent reduction in emissions by 2030 as part of a net zero emissions target by 2050, complements Australian initiatives to develop clean hydrogen to reduce reliance on coal fired plants and as an export commodity. Although neither country has been a leader in climate change action, an agreement was signed by the two prime ministers in January 2020 to explore opportunities with clean hydrogen with the goal of exports of one million tonnes of clean hydrogen to Japan by 2030. It is an encouraging sign that might place pressure on both governments to undertake serious efforts in this regard. Current estimates suggest that exports could be worth as much as AU$26-billion to the Australian economy by 2050. Such a deal reflects the potential for a transition from coal to clean energy in Australia with massive implications for two-way trade as well as the restructuring of the Australian economy. Notably, in January 2022 Australia and Japan extended the framework of cooperation on a clean hydrogen program to include using financial incentives to encourage other countries in the region to be innovative in the reduction of greenhouse emissions.

Concluding comments

The Australia-Japan relationship has undergone extraordinary growth in the politico-security sphere over the past 15 years. Security communities are now familiar with each other through regular bilateral, trilateral (with the US) and quadrilateral (with the US and India) dialogue. The Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA) moreover, ensures that there will be increasing levels of interoperability between Australian and Japanese military forces on a scale that was unimaginable a generation ago

Importantly, the rapid development in security links is an acknowledgement in Tokyo and Canberra that the partnership is an important factor in each countries’ respective security and foreign policy making process. In this context, the fact that Japan has chosen Australia to be the first country other than the United States to sign a security cooperation agreement (2007) and a reciprocal access agreement (2021) is symbolic of how far the bilateral relationship has developed. Indeed security ties are now close to commensurate with the vast commercial links between the two countries.

Of note too is that Japan, despite its reliance on the US for security, has managed to maintain diplomatic dialogue with China as well as a massive trade relationship. The Japanese model is not a neat fit for Australia, but it does demonstrate possibilities for a future Australian re-set with China that includes robust disagreements but also diplomatic communication, trade and cooperation on crucial regional issues of mutual interest.

Finally, the Australia-Japan relationship is multifaceted and has an ever-widening range of mutual interests as demonstrated with cooperation in climate change and zero emissions policies. It is a natural partnership that is based on complementarity and mutual interests that have been able to withstand difficult periods. These commonalities suggest that the bilateral relationship will continue to develop and prosper for many decades to come.

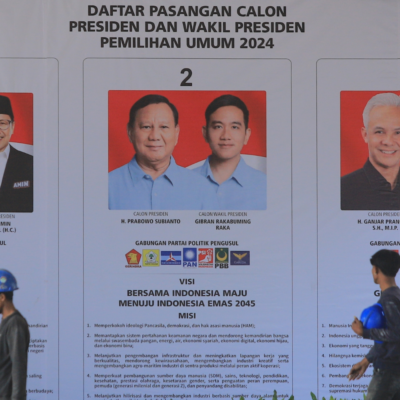

Image: Australian Prime Minister Morrison and Japanese Foreign Minister Hayashi, Melbourne, 2022. Credit: US Department of State/Flickr. This image has been cropped.