In 2021 the Quadrilateral Security Initiative, or ‘Quad’, held its first in-person leaders’ summit convened by US President Joe Biden. The re-emergence and growing prominence of the Australia, India, Japan and US grouping reflects the increasingly risky regional strategic dynamics in which great power competition is set to be a major force for decades to come. In this piece I provide some context to the emergence of the Quad and a number of reflections on its development since its revival in 2017. It concludes with a focus on Australia and the Quad and what that tells us about how a mid-tier democratic power is approaching contested Asia.

It is commonplace today to observe that Asia is experiencing a revival of great power competition driven largely, although not exclusively, by Sino-American rivalry. While the dynamics of that contest have become more visible, and more dangerous, in recent years, the reality is that the uneasy great power comity that had been established by the rapprochement forged by former leaders Richard Nixon and Mao Zedong, had broken down by the early 2010s. Xi Jinping’s accession to power in 2012 married ambition to the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) growing wealth and power and prompted a reconfiguration of Chinese foreign policy; it was no longer willing to live forever in a region it perceived to be shaped to serve American power and interests.

While the administration of former US President Barack Obama had in its early years sought a more collaborative approach to the PRC, although it had no intention of giving Beijing more influence over the region. It then recognised that this was not sufficient to retain Washington’s regional interests, prompting in turn the ‘rebalance’ of US policy toward Asia. While the US did show up to more multilateral summits, joined and then accelerated negotiations about the Trans-Pacific Partnership, perceptions that US credibility and will were not what they had been previously encouraged the PRC to act on its ambitions leading, for example, to the creation of 2,000 acres of reclaimed land in the contested waters of the South China Sea. In relatively short order the region had moved from one in which the absence of great power rivalry had paved the way for a remarkable period of economic growth to one in which the world’s two most important economies were increasingly duelling for influence, albeit still with considerable restraint.

The election of Donald Trump seemed, initially at least, to promise a shift in momentum with the early efforts to cultivate positive ties with Xi Jinping and his willingness to reconsider almost all aspects of US China policy evident in his flirtation with Taiwan during the transition period. The great ‘deal maker’ looked as if he might be cut from Kissingerian cloth. Yet by 2017 the White House had released its national security strategy which placed great power competition at the centre of US international policy, with China a principal focus, and it adopted a hostile approach to trade with the PRC as well. The world’s two most important powers were set on a competitive track. The broad approach to Beijing was and indeed remains one of the few areas on which both sides of US politics agree. It reflects a consensus among policy elites that the PRC represents a threat to US strategic interests as well as a hardening of views about China within the private sector which had hitherto been seen as a force that would constrain the bilateral relationship from deteriorating too much.

The COVID-19 pandemic has served to turbo charge their rivalry. Specifically, Trump decisively hardened his view toward the PRC in early 2020 as he recognised the damage that the virus was having on his political standing and prospects for re-election and framed the pandemic as part of broader an attack on the US. This pushed American policy toward China to stark levels of hostility. For its part, Beijing has also seen the pandemic not as something on which it should build common cause with the US, but as a further front in its contest for influence. More broadly Beijing’s sense that it handled the pandemic successfully and in a manner far superior to the US and other advanced democracies has also served to reinforce Beijing’s elites’ sense that history is on their side.

And it is this context of a region beset by a nearly decade-old dynamic of growing Sino-American rivalry, that led to the revitalisation of the Quadrilateral Security Initiative or ‘Quad’, as it is usually known, in 2017. First established in 2007 with Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe then its most visible advocate, the grouping’s tentative first existence of barely twelve months was notable more for the manner of its ending than anything achieved under its auspices—the Australian foreign minister said the country was walking away from the group in front of his equivalent from the PRC. The lack of enthusiasm for the grouping at the time also reflected the relatively low level of concern about the challenge the PRC represented as well as a sense that it might well create something of a self-fulfilling prophecy by so visibly working to hem China in.

By the time the group reconvened formally, albeit only at the senior official level, the nascent challenge posed by an authoritarian China of 2007 had appeared to have become very real. From the disputed waters of the South China Sea to the standoff between India and China at the Doklam plateau, the friction between Japan and China over the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands, as well as the ongoing expansion of China’s military capabilities had led to a convergence of views about the broader regional circumstances as well as the kinds of mechanisms needed to respond to an unsettled Asian order.

The Quad held its first formal reconvening, with Japan again a key catalyst, at the sidelines of the East Asia summit in November 2017, with a series of senior official meetings held in the following years including the four naval chiefs gathering at the sidelines of the Raisina Dialogue in Delhi in 2018. In 2019, the Quad met at ministerial level alongside the annual UN General Assembly opening in New York with subsequent gatherings in Tokyo in October 2020 and virtually in February 2021. The Quad held its first leaders’ level gathering in person in September 2021 in Washington, following a virtual gathering in March of that year. The four leaders committed to an annual summit to ensure political momentum is maintained, as well as to signal the significance of the grouping; and issued an extensive communique elaborating the grouping’s purpose and increasingly expansive remit. In their words, the Quad exists to promote ‘the free, open, rules-based order, rooted in international law and undaunted by coercion, to bolster security and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific and beyond.’

The return of the Quad after an ill-fated initial existence reflects a number of important trends in Asia’s international relations. Most obviously—notwithstanding the fact that in the approximately 2,000 words of the leaders’ summit communique China is not mentioned once—the Quad’s revival and acceleration is a function of the concern the four countries have about the disruptive effect of the PRC on the region and the need for concerted collaboration to manage the consequences of an increasingly powerful and confident Beijing. Equally, the four countries have developed a consensus about both the challenge the PRC presents and the kind of regional order they wish to prevail in the face of Beijing’s growing power. But it is not just that the four feel that cooperation is needed to manage a contested strategic order—they clearly believe that the wide array of existing multilateral mechanisms are inadequate to the task. Since the mid 1990s the region witnessed a flowering of multilateralism with many mechanisms and groupings established to drive regional security cooperation in particular, such as the ASEAN Regional Forum, the ASEAN Defence Ministers Plus process as well the establishment of the East Asia Summit as a peak collaborative body. That the US, Japan, Australia and India felt the need to establish a new body and develop an ambitious and expansive program of work reveals the lack of confidence they have in the many existing multilateral mechanisms.

Although the Quad was and remains a security organisation—with a particular focus on coordinating military activity and operations—it is telling that the grouping has felt the need to broaden its remit to include vaccination research and distribution, combatting climate change, technology development and educational exchange. This reflects the multidimensional nature of security in the contemporary era as well as the need to have a broader set of areas in which cooperation occurs to improve its political and strategic prospects.

The creation of the Quad and its rapid ascension in the priorities of the participants is a function of the region’s contested strategic dynamics. While framed by the participants in positive and stabilising terms, the reality is that the grouping and its actions are contributing to strategic competition and not acting as a dampener on those contestatory dynamics. The intention is clearly to protect what its members see as crucial components of the regional order: a stable and favourable strategic balance, an open setting for international economic relations, and a broadly liberal approach to the way states manage their international relations. However, this approach to advancing those goals contributes to the competitive regional circumstances and is likely to add to rather than reduce regional contestation.

The Quad has moved through the multilateral gears relatively swiftly, it has set out an ambitious work program across a range of areas including the environment, public health and high technology. But the group is notable, so far at least, for the conspicuous absence of economic matters on its agenda. At first glance this may seem an odd criticism. Among the reasons the four opted to create a ‘bespoke’ institution and not use an existing mechanism was the appeal of a small grouping focused on a specific issue that could move more swiftly than larger bodies encumbered with slow operating systems and unwieldy agendas. Yet if the Quad is fundamentally about protecting a preferred international order in the face of the PRC’s efforts to reconfigure its international environment then the lack of economic matters is a considerable shortcoming. Beijing’s approach to recasting the region, which has to date been fairly piecemeal, has been conspicuously focused on geo-economics; that is, on using economic means to advance strategic goals. Given the scale of its economy, the capital it has accumulated as well as the constraints it continues to face in traditional military terms, it should not be surprising that it is using infrastructure programs, trade agreements, investment and an array of other means to advance its international ambitions. If the Quad wants to protect what it describes as a free and open Indo-Pacific region then it will surely need to develop a coherent geo-economic strategy to complement its security programs. The challenge the group faces is that while there has been a convergence of interests and approaches in the security dimension, the gaps between them on economic matters are significant and may preclude that possibility altogether. Most obviously, the four have quite different approaches to trade, with the exception of Japan they do not have much to offer in terms of infrastructure capacity and would find coordinating capital allocation in the way the PRC is able to do impossible.

Until relatively recently Australia had been optimistic about its region’s prospects and its policy focused on a comprehensive engagement with Asia’ many multilateral mechanisms while also seeking to build positive and durable relations with all of key powers. This began to change in 2017 as the mood in Canberra soured toward China and the sense of optimism about Asia’s future dimmed. In many respects the return of the Quad for Canberra is a product of that shift. In 2008 the government led by Prime Minister Kevin Rudd felt that the risks in the region did not warrant such a body and the country felt that positive relations with the PRC were of a higher priority. No longer. Indeed under both the government of Malcolm Turnbull and Scott Morrison, Australia has made a set of decisions that have led to a significant deterioration of Sino-Australian relations. This included blocking Huawei from participating in Australia’s 5G telecommunications network, introducing foreign interference legislation, and unilaterally calling for an independent investigation into the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic. The bilateral diplomatic relationship effectively does not function, and the PRC has imposed a range of tariffs and non-tariff measures on a number of export sectors that are particularly exposed to the China market. While Australia has largely weathered these well (although individual exporters have suffered considerably) it does not want to suffer China’s ire alone. One of the appeals of the Quad is that it provides the means through which the burden of managing China can be shared. Also, Australia has long sought to have a more fruitful relationship with India but has consistently been unable to sustain a focus on the country for very long. The Quad introduces a high priority means for regular interaction that can help build a more durable partnership with a country that Canberra regards as ‘like-minded’.

The Quad is also a logical outgrowth of the Australia, Japan and the US Trilateral Strategic Dialogue that was first held at vice-ministerial level in 2002 and held its first minister-level gathering in 2005. While Australia has established a vast array of what it describes as ‘strategic partners’ in Asia, curiously including the PRC, its alliance with the US and its security collaboration with Japan are by some margin the most important of its bilateral ties. From a functional perspective, the Quad has a relatively robust foundation with the security communities of the US, Japan and Australia very familiar with one another. Finally, in the best ‘middle power’ traditions (Australia has long been a committed multilateralist) there are no regional multilateral mechanisms which will have it as a member that it has not joined. Yet Canberra has long found the process-orientation of many regional efforts to be frustrating and the role it has played in helping to drive the Quad reflects the appeal of minilateral mechanisms in general and this more results-oriented body in particular.

The Quad has made considerable waves since its return in 2017. It is by some margin the most dynamic regional security grouping, is not hide-bound by process and brings together four significant maritime powers who seek to buttress a broadly liberal international order from China’s efforts to reconfigure the region. Yet to date, beyond some relatively routine military exercises, the Quad has not taken any significant steps to turn its words into deeds. Even after adding vaccine matters to its agenda it was unable to act on its ambitions due to the huge problems faced by India in 2021. There are also doubts about the extent to which the three junior partners to the US can contribute to larger efforts much beyond steps they are already taking, at least in the short to medium term, as each face practical and political limitations to the kind of balancing coalition activity that the Quad’s ambitions imply.

Asia’s international relations will be shaped profoundly by great power competition for at least a decade if not much longer. Quite what part the Quad will play in this remains difficult to discern as, so far at least, it operates principally as a signalling exercise. If, however, it is able to build on the existing strategic consensus between its members and it becomes a major component of Asia’s security architecture then it is likely to stoke competition rather than damp it down. The Quad seeks to limit China’s capacity to change the region while Beijing is intent on a new dispensation in Asia. And as this ambition is unlikely to change under the current leadership a militarised contest in Asia seems likely. And it is the scale of the contest, the multi-dimensional nature of security interests and the number of ways in which competition could escalate that makes the region such a dangerous place.

Author: Nick Bisley is Dean of Humanities and Social Sciences and Professor of International Relations at La Trobe University.

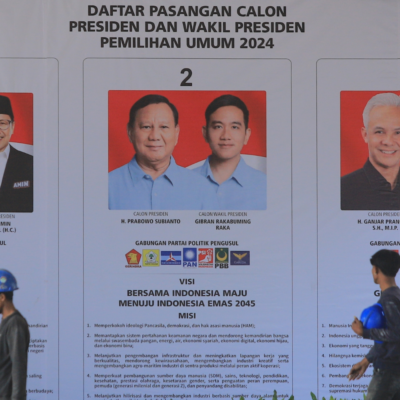

Image: US Secretary of State Antony Blinken Meets with Indian External Affairs Minister Jaishankar, during a trip to Melbourne for a Quad ministerial meeting, Februray, 2022. Credit: US State Department/Flickr.