It seems that in 2020—according to the latest figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS)—Australian investors were ‘quietly making their own exit’ of China amid deteriorating relations. At the same time, however, according to the United Nations Committee on Trade and Development China became the world’s largest recipient of foreign direct investment (FDI), with flows rising by four percent in 2020 to USD163 billion.

In a commentary, the former deputy editor of the Australian Financial Review Greg Earl argues that this ‘voluntary quiet departure by Australian investors from the region’s biggest economy’, including by services companies like online employment business Seek, represents an ‘interesting sovereign-risk decision’.

Australia’s FDI in China, which more than halved last year according to the ABS figures, clearly illustrates perceived risks by Australian businesses with a China presence. As the Chinese idiom goes, ‘ducks are the first to know when spring comes and water warms’ (春江水暖鸭先知). Only in this case, Australian companies are the first to sense the cold and danger, though they have largely chosen to remain quiet in public debate.

Chinese investors’ even earlier departure

Interestingly, such sovereign risk/s associated with shifting regulatory environment in the destination country and worsening bilateral relations have been sensed by Chinese investors in Australia even earlier, from 2017 and 2018.

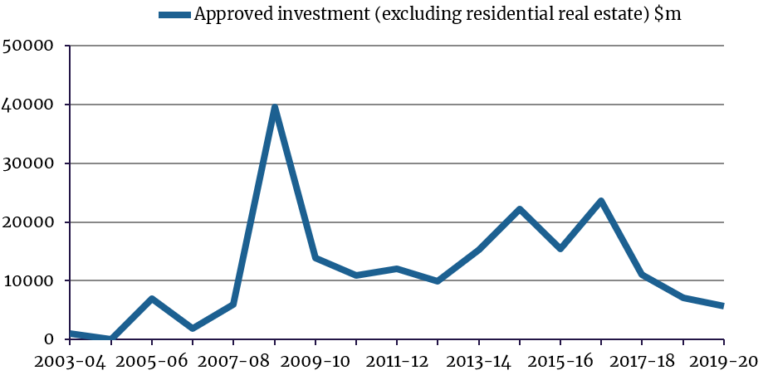

While Australian investment in China has long been minimal, Chinese investment in Australia surged in the financial year 2005-06 to AUD7.259 billion, ranking the third among investor economies. Statistics from Australia’s foreign investment screening body, Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB), indicates that since then, investors in Australia from Mainland China remained in the top three (except for 2006-07 (when it was eleventh) and 2007-08 (sixth), until it dropped to the fifth in 2018-19 and sixth in 2019-20.

The fall in investment volume is more startling than that in ranking. A compilation of FIRB annual reports below illustrates that approved Mainland Chinese investment in Australia (excluding investment in residential real estate which tends to be initiated by individual investors) experienced a 53.2 percent decrease in 2017-18 and the volume further halved over the next two years, back to the level of Chinese FDI 15 years ago.

Approved Chinese Investment in Australia (financial years 2003-04 to 2019-20) (excluding SARs and Taiwan, excluding residential real estate) (Million AUD).

Compiled based on Annual Reports by the Foreign Investment Review Board

Admittedly, approved foreign investment is subject to a variety of factors including, for example, restrictions China imposed on ‘irrational investment’ overseas from late 2017. Annual flow of Chinese investment to Australia as summarised above testifies to that restraining factor, with a downward trend in the calendar years 2017-18.

The two financial years of 2018-19 and 2019-20 saw enthusiasm from Chinese investors in Australia further dampened, with year-on-year decline of 36 percent and 20 percent respectively. During the same period, however, Chinese foreign direct investment saw a mild decrease of 4.3 percent and 2.9 percent. Even taking into account the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the zero screening threshold Australia imposed on foreign investment in March 2020 the exit of Chinese investors from Australia is evident.

Confirmation from major investment trackers

This exodus of Chinese investors has been confirmed by both major Chinese investment trackers in Australia: the Demystifying Chinese Investment in Australia series by KPMG/University of Sydney; and the Australian National University’s Chinese Investment in Australia (CHIIA) Database.

The Demystifying Chinese Investment in Australia report draws on KPMG and the University of Sydney Business School’s database, with ‘raw data [collected] from a wide variety of public information sources’. The initiative which started in 2011 tracks Chinese investment in Australia, ‘including by subsidiaries or special purpose vehicles.’

Their latest report in July 2021 confirms 2018 as the watershed for Chinese investment in Australia: the USD6,243 million recorded in calendar year 2018 was only 62 percent of the 2017 level; and it shrank further in 2019 to around one third of that in 2018. There was a further 18 percent decrease in 2020.

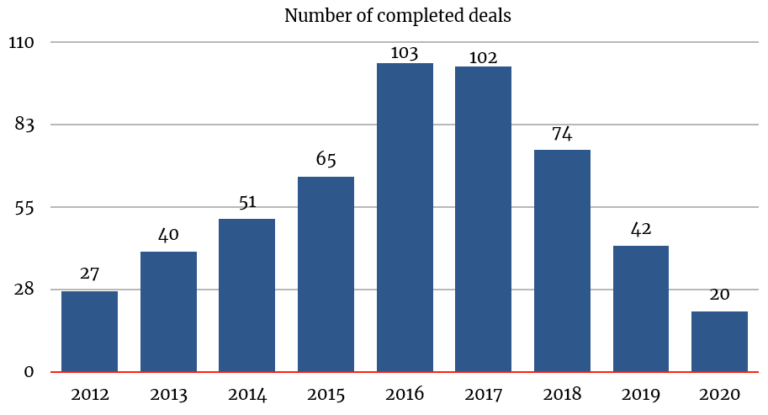

The number of completed deals registered by their database shows a downturn in 2018. It dropped by 27.5 percent from peaks in 2016 and 2017 to 74 cases in 2018, and then further down to 42 in 2019 and 20 in 2020. The number of completed deals is arguably a more apt indicator of investor sentiment than investment volume, which can be easily skewed by mega deals.

Number of completed Chinese investment deals in Australia

Compiled from KPMG/University of Sydney Demystifying Chinese Investment in Australia reports 2012-2021.

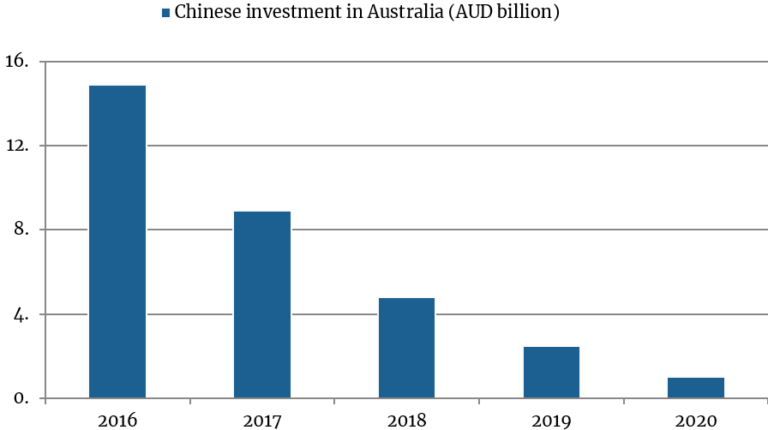

The ANU CHIIA’s database tells a similar story, but indicates a downturn a year earlier than the KPMG/University of Sydney dataset: Chinese investment in Australia peaked in 2016 at AUD14.9-billion but has since plummeted to just over AUD1-billion in 2020. Based on a new methodology developed by ANU’s East Asian Bureau of Economic Research, it has tracked Chinese investment in Australia from 2014.

Chinese investment in Australia (2014-2020)

ANU Chinese Investment in Australia (CHIIA) Database

Higher risks perceived by China

Two developments in 2021 seem to indicate a new level of risk perceived by the Chinese side: China Investment Corporation’s planned exit of its stake in Sydney’s landmark tower Grosvenor Place; and Australia’s drastic decline among investment destinations as assessed by China’s top think tank Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

China’s biggest and world’s second biggest sovereign wealth fund China Investment Corporation (CIC) holds a 25 percent stake in the Sydney office tower from a 2015 transaction and outbid competitors in November 2020 for a further 50 percent. While Australia’s Foreign Investment Review Board finally approved the acquisition mid-2021, the decision took more than six months (the longest time frame under the screening mechanism). Reports about CIC’s possible retreat from the deal were finally confirmed half a year later when ‘US group Blackstone snapped up [the] half stake’ instead. Australian Financial Review earlier on reported that CIC is also ‘selling out the 25 percent it holds’.

It is true that CIC has not invested as heavily as before in real estate from 2018, but turning back on its ambitious bid only ten months ago would still be an alarming signal. While the deal was seen at that time as ‘a vote of confidence for the Australian capital markets’ and demonstrating ‘strong investor appetite for core product in gateway cities’, CIC’s planned pullout now can be taken as a clear sign of concern among Chinese investors.

This is echoed by the revised risk assessment of Australia as an FDI destination in the annual report of China’s leading think tank, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS). The CASS Institute of World Economics and Politics has been issuing ‘Country Risk Rating of Overseas Investment from China” (CROIC-IWEP) since 2014, assessing potential direct investment risk in destination countries for Chinese businesses.

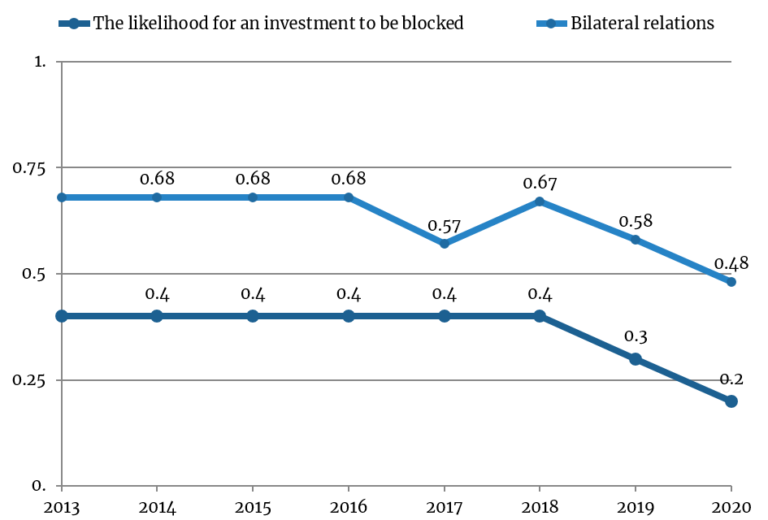

Australia’s position as a long-time top four throughout the 2014 to 2020 reports, covering the period of 2013 to 2019, has been downgraded to 15 in the most recent 2021 version. In addition to soaring deficit, the downgrade can be mostly attributed to a more negative assessment in categories of ‘the likelihood for an investment to be blocked’ and ‘bilateral relations’, both of which are calculated with the Delphi method. For the purpose of this assessment, a panel of Chinese experts in areas of economics, international relations and law are surveyed. These two are among the only three indicators to rely on expert assessment, rather than statistics from international organisations or business intelligence. Therefore, the reduced rating on Australia’s investment environment and relations with China represents strong evidence for higher FDI risk in Australia in 2020 as stated by top Chinese scholars .

CROIC-IWEP rating of Australia for indicators ‘the likelihood for an investment to be blocked’ and ‘bilateral relations’.

Assessment for calendar years across 2013 to 2020, as published in reports 2014-2021) (The risk assessment is a number between 0 and 1, the lower the number, the higher the risk for Chinese investment)

Source: CROIC-IWEP reports 2014-2021.

The essential problem is declining levels of trust

What is revealed above is significant for the ongoing debate on China-Australia relations in that it illustrates how frontline businesses from both countries have, though not discussed much in mainstream media, responded to perceived sovereign risk. Given their proximity to action, it would almost certainly mark the beginning, rather than the end, of an ongoing trend, thus challenging the ‘business as usual’ assessment commonly seen in Australian media in relation to trade numbers and economic relations (when assessed separately from diplomatic relations).

The shifting pattern in foreign investment activities is also important in that, while trade has caught most headlines, it is the volume of capital flow between countries that speaks to the declining level of trust and good will, on which exchange and connections in other areas may only develop. As former prime minister Tony Abbott aptly summarised when welcoming President Xi Jinping to the Australian Parliament during his 2014 visit to Australia: ‘We trade with people when we need them, but we invest with people when we trust them’.

This focus on trust and good will has long been the Chinese government’s foreign policy position. A catch phrase for it is 政治互信 (mutual political trust). In mid-2019, for example, former Chinese ambassador to Australia Cheng Jingye delivered a speech, themed ‘mutual political trust, cooperation boost China-Australia ties’. In what is a standard delivery of government position on this, he said, ‘Mutual political trust and mutually beneficial cooperation are just like two wheels that would smoothly drive our bilateral relationship forward.…Both of them are indispensable. The relationship between China and Australia can only be steadily and increasingly improved when both wheels are spinning with the same speed and in the same direction, mutually reinforcing each other’.

The current level of trust between China and Australia is undoubtedly very low, set on a downward trajectory when Australia’s assessment on China’s Belt and Road Initiative started to shift in 2017, accelerated by accusations of China’s interference in Australia’s politics and tightening geopolitical rivalry, among other issues.

China’s assessment on Australia changed too, from a welcoming economic partner (or indeed exporter and investment destination) to a determined member of the ‘like-minded countries’ against China. Expert assessment on ‘bilateral relations’ in CROIC-IWEP may help put it in better context: the 2018 rating of China-Australia relations at 0.67 fell in 2019 to 0.58 in 2019 (approximately the same level of 2017 when the Turnbull government introduced foreign interference laws) and down further to 0.48 in 2020. For both 2019 and 2020, Australia was rated among the lowest of more than 50 investment destinations—lower than Canada (0.56 in 2019), but still higher than the US (rated 0.42 in 2019 and 0.40 in 2020), and India (0.47 in 2020).

A decoupled future?

With the central element of ‘trust’ crippled what does it imply about China’s future economic policy towards Australia and the two nations’ economic relations? To put it simply, from China’s perspective, it is now a rational choice to avoid Australia as much as possible due to the higher perceived risks.

Starting with investment, Australia’s capital flow to China is set to remain minimal, with the departure of Australian services companies and, more recently, consultancies facilitating Australian investment in China.

Investment the other way around is not expected to recover in the near future either. Though surging Chinese investment in Australia since 2005 has largely been celebrated as part of closer economic ties, its downside has not been readily acknowledged in either China or Australia. The sudden influx of Chinese capital has been intimidating by some segments of Australian society and, with a conservative government and heightened geopolitical rivalry, framed as a threat to ‘national security’.

Our comparative study on foreign investment regulation in advanced economies indicates that not only is ‘Australia …not alone in taking great account of national security issues in its investment regimes’, as declared by FIRB Chair David Irvine in October 2021, Australia has pioneered this wave of regulatory responses across the industrialised world. Paradoxically, the host countries that draw the most Chinese capital tend to see the most controversy surrounding it.

This caution towards Chinese businesses is evident with both state-owned enterprises and private companies, with each emerging interest of Chinese capital over the past two decades quickly becoming the target of regulatory responses and thus dampened, from mining, agri-business, infrastructure and, more recently, health care. The prolonged screening on CIC’s commercial real estate investment sounds the latest alarm.

What about trade? The majority, if not all, of Australia’s export consumer products to China can be readily replaced. In relation to dairy products, for example, New Zealand has long dominated importers to the Chinese market, with Australia lagging far behind with the Netherlands, Ireland, Germany and France. Customs statistics for 2019, show New Zealand accounted for 40.77 percent of Chinese dairy imports, the Netherlands 15.87 percent, Ireland 8.18 percent and Australia 7.04 percent. For wine, fruity Chilean, Italian and Spanish products which are also favoured among beginner drinkers quickly took over the space left by Australian brands; and French wine instantly recovered its ranking as the top importer of wine to China, just a year after Australia held that position.

Tourism will prove to be dependent on readiness of flights to Australia, how welcome Chines tourists believe they will be, and comparative advantage against other long-haul tourist destinations.

For education, Australia may very well continue to be a popular destination for Chinese students, but growth of student enrolments is expected to slow. Even before COVID-19, the high growth rate in 2017 and 2018 had slowed in 2019. The impact is set to be greater on the smaller non-Group of Eight, universities than those in the Go8.

In terms of resources, serious efforts have already been made in China to find alternative sources and diversify. After all, ‘decoupling’ in a world of heightened geopolitical rivalry and ideological grouping means more self-reliance and self-sufficiency. As J. Stewart Black and Allen J. Morrison wrote in their piece for Harvard Business Review, despite ‘…the popular view in the United States that decoupling largely involves discouraging imports so as to safeguard or repatriate U.S. jobs…’, among others, (and in Australia that decoupling is more about diversifying export markets), ‘[f]rom the Chinese perspective…decoupling is a strategic shift…’, with the key objective of ‘eliminating its dependence on foreign countries and corporations for critical technology and products’ (and in the case of Australia, resources). One would just need to look at the level of resources investment China has made to understand how conscious it has been of that deficiency.

It would be hard to predict how effective those efforts will be across various mining exports. But from what can be seen so far, the will on the Chinese side is firm and strong.

This would present a fundamental challenge to an assumption made in much of the debate on Australia’s China policy that economic ties can be built without political trust first being rebuilt. It would be a grave challenge for any future Australian government to figure out a way to drive forward relations with China on only one wheel.

Author: Assistant Professor Diane Hu, Australian Studies Centre, Beijing Foreign Studies University and Associate, Centre for Contemporary Chinese Studies, University of Melbourne.

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [2019JJ013]

Image: An iron ore mine in Western Australia. Credit: Ginger_ninja/Flickr