Privatised violence—physical force exercised by street gangs, vigilantes, militias and the like—has accompanied the development of the state in Indonesia.

In the decentralised democratic era since 1998, these groups have proliferated, and many are increasingly concerned with Islamic morality and claim to enforce the Qur’anic edict amar ma’ruf nahi munkar (commanding virtue, combating vice). But in the past, during the authoritarian era of former President Soeharto, these groups mobilised behind Indonesia’s national ideology Pancasila, which consists of belief in God, a fair and just society, Indonesian national unity, democracy and social justice.

The director of the Institute for Policy Analysis of Conflict, Sidney Jones, views the Islamisation of privatised violence as an indication of the rise of Islamic militancy. Jones further argues that Islamic vigilantes could become fertile ground for jihadists—militant Muslims who aim to establish an Islamic state with violence.

But such analysis exaggerates the fact that employing Islamic identity is only a tactic to respond to a new environment where Islam has become a powerful source of mobilisation. The adoption of an Islamic identity is part of the way street gangs, vigilante groups and the like enhance their position in racketeering and establish predatory alliances with political elites.

These groups continue to depend on establishing patronage relationships with political elites, instead of being more autonomous as institutionalists argue. Institutionalists argue that decentralised democracy in Indonesia has changed the pattern of patronage politics and made the state more fragmented, so that centralised control over violent groups can no longer be established. Articulating Islamic rhetoric and identity, according to this perspective, is seen as a new way to establish legitimacy. As I will show below, Islamisation of street gangs has instead affirmed their continuing reliance on powerful politico-business elites to thrive.

Islamic conservatism on the rise

The proliferation of Islamic street gangs in post-authoritarian Indonesia must be understood within a context of rising Islamic conservatism, which is characterised by anti-pluralism and illiberalism. Mainstreaming Islamic conservatism means that Islam plays a bigger role in socio-cultural life than before, but it is not necessarily followed by the formalisation of Islam within state institutions.

Conservative Muslim groups and their followers are fragmented—there is no feasible and coherent political vehicle that could represent their interests, so they establish alliances with political elites. Powerful secular politicians also need to build alliances with conservative Muslims to gain their support in elections. As a result, Islamic conservatism remains politically marginalised, but it has become a new powerful source of mobilisation as a way for Islamic groups to ingratiate themselves with politicians wanting to appeal to conservative Muslim voters. Street gangs, vigilante groups and the like have therefore turned away from defending the principles of Pancasila, to defending conservative expressions of Islam.

Rising Islamic conservatism is best understood as more than just a socio-cultural expression, because it is also a response to rising economic precarity and political disillusionment. It is a manifestation of what scholars Vedi Hadiz and Angelos Chryssogelos describe as the broken promises of modernity, in which industrialisation was expected to increase the size of the educated middle class as a backbone of secular society and liberal democratic politics.

In many contexts, including in Indonesia, modernity has instead resulted in socioeconomic insecurity. In some caculations, Indonesia’s ‘middle class’ expanded from 25 percent of the population in 1999 to 65 percent in 2020, but 69 percent are categorised as ‘aspiring middle class’ and remain economically insecure. As such, instead of fostering secularisation, many middle-class Muslims turned to religion and embraced Islamisation to address their anxiety. Some scholars such as Alejandro Colás have identified other factors for the rise of conservative Islam like the relative absence of the political left. In Indonesia, left politics has been exceptionally weak especially since the 1965 communist massacre. With no alternative, Islam has become the dominant articulation of socioeconomic disillusionment and political dissent.

The trend of middle-class Indonesian Muslims turning to religion can be observed in a number of ways. One of them is the increasing consumption of Islamic commodities, socioeconomic products that represent religious piousness. Another is that Indonesian youth now commonly express a devout Islam, a phenomenon known as hijrah which literally means ‘to migrate’. One of the ways this is revealed is in youth fashion and physical appearance. Gated Muslim housing estates have also become popular, as has Islamic banking, Islamic education and Islamic herbal medicine.

The Islamisation of street gangs, vigilante groups and the like is a response to the rising trend of Islamic conservatism. Many of these groups have also turned to Islamic identity and rhetoric, such as amar ma’ruf nahi munkar to help them enhance their influence in racketeering and establish alliances with politico-business elites.

A tactic to enhance prowess rather than a path to jihadism

Terrorism experts such as Sidney Jones claim that Islamic vigilantes have developed into more than just groups that are concerned with upholding Islamic morality—she argues they could become a source for terrorist recruitment. According to this analysis, participating in anti-vice (nahi munkar) raids and the intimidation of religious minorities could become a path to becoming a jihadist, blurring the boundaries between Islamic vigilantes and terrorist groups.

But members of Islamic street gangs mostly have no religious credentials, and don’t aim to establish an Islamic state. Further, there is little evidence that the transformation of street gangs and vigilante groups into terrorist organisations has occurred.

One group, Tim Hisbah (the most prominent Islamic vigilante group in Indonesia of the late 2000s) has been accused of transformation from vigilantism to terrorism. According to a police report, members of Tim Hisbah were involved in several suicide bombings in Solo and Cirebon, West Java, making the group a target of counter-terrorism police.

A 2012 report of the International Crisis Group stated that Tim Hisbah had become a terrorist group in 2010 after its leader Sigit Qordhowi expressed sympathy for Abu Bakar Ba’asyir, a key figure of Indonesian jihadists. Sigit was also reported to have planned an attack on police after a member of Tim Hisbah was killed in an anti-terrorism operation in North Sumatra. In 2011, Sigit and another Tim Hisbah member Hendro Yunianto were shot dead in a police raid. Other members were arrested for having firearms and accused of having been involved in a plot to attack police.

But my interviews show that while Islamic vigilantes like Tim Hisbah might have associated themselves with terrorist groups and showed sympathy for jihadist figures, this is mostly aimed at increasing intimidation in racketeering. Sigit and other members of Tim Hisbah had never received intensive Islamic teaching but had found Islam to be a useful way to engage in racketeering, as had been done by others before him such as Kalono and Yanni Rusmanto, who were involved with private violent groups but not terrorism.

Kalono, with the Islamic Youth Front of Surakarta (Front Pembela Islam Surakarta, FPIS), and Yanni, with the Hisbullah militia, dominated control over Solo’s underworld in the early 2000s, conducting anti-vice raids. In the mid-2000s, both Kalono and Yanni stopped using Islamic vigilante groups for racketeering after successfully undertaking legal and illegal business activities with members of the police and army. This opened the way for Sigit to take control of Solo’s underworld using Islamic rhetoric. He then established several Islamic vigilante groups, including Tim Hisbah, in 2008. For figures like Sigit, employing Islamic identity which is instrumental in racketeering is not a sign of radical transformation from vigilantism to terrorism.

Importantly, ‘confessions’ made during police interrogation, in which Tim Hisbah was defined as a terrorist group, can be highly misleading because police often used torture and intimidation to force ‘confessions’. A scholar of Islamist politics John Sidel points out that many terrorism experts draw an alarmist picture of Islamist politics “based on an uncritical over-reliance on official resources drawn from the security services of the region”.

A member of Tim Hisbah, Edy Jablay, who was jailed after Sigit was killed, claims he was tortured and intimidated by police during interrogation. In my interview (October 21, 2016) he said:

Intimidation during police interrogation is normal. I was tortured by the police. Among other suspects [from Tim Hisbah], I received the worst treatment. Others easily admitted after being beaten. I was not. I was electrocuted. I felt something sharp was pinched to my veins and my feet, which were then electrocuted. My mouth was plastered, while my eyes were covered. My hands were cuffed behind my back and my feet were in chains. I was forced to admit that I was involved in the terrorist plot, that I was a terrorist due to my ideological view about Islam.

He further said that he was forced to confess that he planned a terrorist act, attacking the police, and that it was related to his views on Islam and the Indonesian state:

I can accept if I was punished for possessing guns, but not for having a certain view on Islam or on [the] Indonesian state. Those views cannot be punished. Many of my friends were not involved in the case of gun possession, but just because we attended the same Islamic teaching in Tim Hisbah, they were arrested and punished. They were forced and directed to admit that Islamic Sharia was compulsory, and that [the] Indonesian state was infidel (kafir). In the end, they received punishment, even higher than mine.

Edy also claims Tim Hisbah was not a terrorist group, but only concerned with amar ma’ruf nahi munkar. He conceded that many Tim Hisbah members often attended sermons given by jihadist figures like Ba’asyir or Aman Abdurrahman, but all those events were public and there was no attempt to hide from authorities because the event and the views expressed were not terrorist-related. He also admitted possessing illegal guns, which he claimed was defence against possible attacks by police.

After the killing of Sigit, Tim Hisbah disappeared, as had occurred with other Islamic vigilantes. New figures have emerged such as the Lascar of Islamic Ummah of Surakarta (Laskar Umat Islam Surakarta, LUIS) led by Edi Lukito, which dominates Islamic racketeering in Solo by articulating the same narrative as Tim Hisbah.

Islamic vigilantes remain marginal in the political arena

So far, Islamic vigilantes have been more active in taking part in power contests to thrive, rather than supporting jihadism. Employing Islamic rhetoric not only enhances their prowess, but also helps establish alliances with political elites.

In the 2017 Jakarta gubernatorial election, for example, the most famous Islamic lascar in Indonesia, Islamic Defender Front (Front Pembela Islam, FPI) undertook a leading role in mobilising Islamic sentiment to undermine the incumbent, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama popularly known as Ahok, who was not Muslim and was accused of blasphemy. Hundreds of thousands of conservative Muslims took part in mass rallies led by the FPI. Not long after the first mass demonstration was held, Ahok’s political rivals—all of whom had never been associated with conservative Muslims before—claimed that they supported the protests. Previously, politicians were keen to not be associated with the FPI due to its involvement in violence.

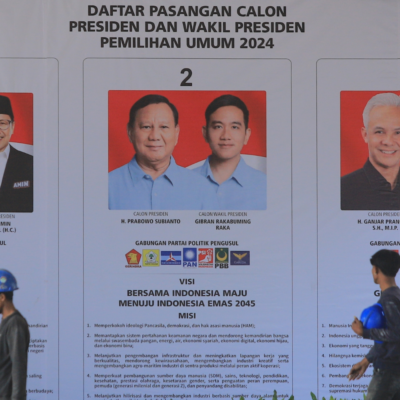

Islamic vigilantes like the FPI might play an important role in power contests, like mobilising votes from conservative Muslims, but they remain marginal in the political arena. The informal alliance between the FPI, conservative Muslims and opportunist politicians successfully resulted in the conviction and jailing of Ahok on blasphemy charges. The representative of this alliance, Anies Baswedan, was subsequently elected as the Governor of Jakarta, but he has not implemented policies or been involved in passing laws that favour conservative Muslims’ interests. Further, in the 2019 presidential election, the FPI and conservative Muslims supported Prabowo Subianto, but he was defeated and later that year, Prabowo threw his support behind his political rival President Widodo.

The Islamisation of privatised violence is not becoming a path to terrorism and Islamic vigilante groups are far from being fertile ground for the emergence of new jihadists. Instead of participating in terrorism, members of Islamic vigilante groups have been more active in trying to establish alliances with politicians, thereby enhancing their power and prowess. The Islamisation of privatised violence also shows how street gangs continue to rely on establishing patronage relationship with powerful political elites to thrive.

Image: Lascar of Islamic Ummah of Surakarta, Solo, Central Java, 2016. Credit: Author.