At the start of 2020, the Middle East was already in political and economic turmoil, and in no shape to cope with COVID-19.

When the worst pandemic for a century, struck the region early this year, the region’s stand-out features were:

- Devastating civil wars in Syria, Libya and Yemen over the past decade, which had caused appalling casualties, suffering and displacement among civilians amid near total economic collapse.

- Overcrowded refugee camps providing inadequate care and shelter within Syria, Yemen, Iraq and Libya and in neighbouring countries, particularly Lebanon, Turkey and Jordan.

- Congested, largely impoverished urban areas, particularly Gaza and central parts of other major cities in the region.

- Underfunded health systems in most states, with the exception of Israel and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC – comprising Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, Qatar and Oman).

- Minimum trust levels between governments across the region and the people they govern—a consequence of inefficient and unrepresentative governance and widespread corruption.

- Economies that were performing poorly because of their inherent weaknesses—particularly substantial dependence on one resource (oil/gas in the Gulf states, tourism in states with attractive shore lines or archaeological/religious sites) and subsistence farming across much of the region. Gulf economies were already suffering because the average oil price per barrel had fallen precipitously from US$95 in 2014 to US$48 in 2015, making only modest annual gains to US$57 in 2019. The breakeven price for the largest producer, Saudi Arabia, had hovered around US$80 over that period.

- A deep split within the GCC from 2017, with Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain, supported by Egypt, placing economic sanctions on Qatar over Qatar’s hosting the Al Jazeera media network and support for the Muslim Brotherhood. This division crippled the GCC, which until then had been the most effective vehicle for mutual political and economic cooperation in the Arab world.

- Tensions between the US and Saudi Arabia, with US congressional representatives (if not President Donald Trump) incensed with Saudi Arabia over the murder of Saudi expatriate journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in 2018.

- Palestinians angry and restive over the prolonged breakdown in negotiations with Israel over a Palestinian state following the failure of then-US Secretary of State John Kerry’s regional shuttle diplomacy in the latter stages of the administration of former US President Barack Obama.

- Political instability in Israel, with the electoral system unable to deliver a conclusive result in two Knesset elections in 2019 and another in early 2020. Added to this, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s standing and authority were reduced further when he refused to stand down from his office after being indicted on charges of bribery, fraud and breach of trust in early 2020.

Enter the pandemic

COVID-19 spread quickly across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) from February 2020, reflecting the fact that the Middle East is a crossroad between Europe and Asia.

The outbreak has been most severe in Iran, where it evidently arrived direct from China, with which Iran has developed significant commercial ties in recent years to compensate for Western sanctions. The situation was worsened by the slowness of the Iranian government in imposing restrictions, not least because it was focused on rigging the parliamentary elections in late February and boosting turnout amid widespread public indifference. The regime accordingly took time to acknowledge the scale and gravity of the problem. The government also did nothing initially to curb visits by Iranian and Arab Shia pilgrims to religious shrines in Iran.

Once established in the region, the effect of COVID-19 on Middle East countries has varied depending on whether they are wealthy, poor or in conflict—as have government responses.

Reported numbers of virus-related infections and deaths in the region are generally unreliable. Many MENA governments have limited testing capacity. Most deliberately understate their figures for domestic political reasons, or to save face internationally. However, the official data provide indications of trends, and these are alarming. They show that while containment measures caused numbers to dip in the early stages of the pandemic, the region has since experienced a rise in infection rates as most states have tried to keep their economies functioning.

A positive factor is that the region’s population is mostly young and healthy—nearly two-thirds are under 35. That tends to make them less vulnerable to the virus. But that advantage is undercut across much of the region by public health inadequacies. Though the GCC states and Israel have Western-standard medical facilities, the other 16 Arab League countries and Iran have poor healthcare infrastructure.

With oil and gas the region’s most lucrative export, the collapse in hydrocarbon energy prices due to the abrupt fall in global economic activity from the start of the pandemic has caused significant problems for Middle East states.

Firstly, it has disrupted the economies and budgetary projections of the energy producers, mainly the Gulf Arab states, causing them to focus on their internal economic difficulties. The oil price fell from US$57 in 2019 to US$11 briefly in March 2020, though it has since risen to around US$40.

Consequently, non-hydrocarbon, and hence relatively indigent, Arab states such as Egypt, Jordan and Lebanon, which could expect to receive financial assistance from wealthier Arab states during economic slowdowns, largely have to fend for themselves.

The situation in the region becomes clearer if analysed in terms of the three broad state types.

Wealthy states

Gulf Arab governments are autocracies, so can enforce social restrictions. Their substantial foreign reserves mean they can cushion the impact of economic shutdowns by increasing subsidies for citizens in much the way Australia has.

However, all GCC states have a substantial foreign labour force mostly employed in building and maintaining the physical infrastructure of their economies. Qatar, in particular, has a huge construction program under way to prepare for its hosting of the 2022 FIFA World Cup. According to Human Rights Watch, these labourers, mainly from the Indian subcontinent and poorer Arab states such as Egypt, tend to live in crowded camps, often with several individuals to a room. Their living and working conditions preclude social distancing.

Those who become sick are not automatically eligible for state-funded health care, and they cannot afford private health care. Many have lost their jobs because of the economic downturn. They seek to return home, and the host governments want them out. But they are hampered by lack of flights, and often reluctance by their national governments to take them back because of fear the returnees may be infected with the virus.

Meanwhile, these workers are a potential source of infection of the wider community. Host governments have little choice but to provide basic medical and other welfare assistance for them or, where possible, to demand that employers shoulder this responsibility.

Gulf Arab states appear now to have instituted good testing regimes, though there are question marks over the accuracy of some of the data. For example, according to Worldometer’s global listing of COVID-19 cases based on individual government reporting (on which all COVID-19 statistics in this report are based), Saudi Arabia had reported 359,000 cases and 5,954 deaths by mid-December—probably a reasonable accounting. Qatar on the other hand had reported only 239 deaths from 140,000 cases, which seems low. Moreover, the extent to which Qatar’s numbers include foreign workers is unclear.

Israel appeared to have got the virus under control in May as new infection numbers reduced to a few dozen a day. That led to an easing of restrictions, with schools, restaurants and bars reopening and employees returning to workplaces.

Subsequent sharp rises in the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths, culminating in 344,000 cases and 2,909 deaths by mid-December, have forced the government to reimpose many restrictions, including a second lockdown in September. This was unpopular with many Israelis as Prime Minister Netanyahu, under pressure from the corruption charges against him, was accused of coddling his Ultra-Orthodox allies, who reportedly flouted medical guidelines.

Israelis have grown less observant of the restrictions. Mobile-phone data show they moved around just 60 percent of normal under the second lockdown down from 75 percent compliance during the first lockdown in March.

Iraq is technically among the Middle East’s wealthier states because of its major hydrocarbon resources. Its oil industry has gradually returned to pre-2003 levels—Iraq exported nearly four million barrels per day (mbd) in 2019, enabling GDP growth of 4.4 percent.

But the crash in oil prices and global COVID-19 restrictions put paid to that. The World Bank expects the economy to have contracted by 9.5 percent in 2020—Iraq’s worst annual performance since 2003. Moreover, though the country’s wealth should have meant a gradual rise in living standards, Iraq is in constant political crisis—evidenced by large demonstrations against corruption and the cost of living in 2019. As well, the country’s religious divisions are demonstrated by the free rein given to Iranian-backed Shia militias that operate beyond the control of the Iraqi government.

Reflecting the country’s appallingly bad governance, Iraq has the highest number of recorded deaths among Arab states: 12,400 as of mid-December among a population of about 40 million.

Poorer states

Egypt’s official figures show the second highest death toll in the Arab world, 6,750 deaths as of mid-December, though that number certainly understates substantially the true extent of the virus in this densely populated country of some 100 million. The rate of testing in Egypt, 9,690 per million, has been significantly less than Iraq’s 95,963 per million.

President Sisi has used draconian measures to quell criticism of his handling of the virus. Egypt’s security agencies have arrested health workers who have drawn attention to medical and personal protection inadequacies.

The virus has had a devastating impact on Western tourism, one of Egypt’s main sources of income. In mid-year the government decided that it had no choice but to live with the virus. It declared a reopening of workplaces, restaurants and major airports, with foreign tourists encouraged to travel to resorts on the Red Sea and the Mediterranean. Unsurprisingly, few foreign visitors have come.

Iran has the region’s highest official infection rate and death toll—over a million cases and 50,000 deaths as of mid-December—but even this figure is believed to understate the real impact. The situation has similarities with that in the US—ironic given the hostility between the two. In both, spread of the virus shows no sign of slowing and public distrust of official directives has been reflected in the flouting of social distancing restrictions.

Lebanon, with about 1,200 reported deaths from the virus among a population of 6.7 million, is not among the worst-affected states in the region. But the country has experienced a range of economic blows in the past two years culminating in the devasting explosion at Beirut port in August 2020, which caused nearly US$5 billion in immediate damage and underlined the country’s infrastructural vulnerabilities.

In the second half of 2019, with protests mounting in Beirut and other cities against new taxes and corruption, confidence in the Lebanese lira plummeted. Its black market rate fell 80 percent below its official rate. Inevitably, inflation soared. By March 2020 the Government had defaulted on a $1.2 billion Eurobond loan – Lebanon’s first ever sovereign default.

The pandemic accentuated the process, throwing people out of work and causing small businesses to collapse. Moreover, the global economic slowdown reduced remittances from Lebanese working abroad. The World Bank has estimated that Lebanon can expect lower revenues, higher inflation and a further rise in poverty through to the end of 2021.

Other poorer Middle East states are not in as dire a situation as Lebanon, but they are headed in that direction. Jordan had early success in containing the virus through rapid declaration of a state of emergency in March and implementing strictly enforced restrictions. But once these were eased in mid-year, infection numbers shot up—3,370 deaths had been recorded as of mid-December. With the important tourism sector dormant and remittances down, the World Bank expects the Jordanian economy to contract by 5.5 percent and poverty to rise by 11 percent 2020.

States in conflict

Though not formally concluded, the war in Syria is winding down. With help from Russia and Iran, Bashar al-Assad has effectively won. He now controls the entire country apart from the north-western province of Idlib.

He is currently held back from a final offensive on Idlib by Russia, which with Iran provides vital military support to the regime. Russian President Vladamir Putin wants to maintain a working relationship with Turkish ruler Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who is determined to prevent a further flow of refugees from Idlib into Turkey if the fighting resumes.

The war has caused untold human misery. Deaths now number almost 600,000. Some 6.7 million Syrians, of a pre-war population of 18 million, are internally displaced, living in often-damaged housing or collective shelters. And 5.6 million are registered as refugees outside the country in the largest displacement crisis since World War II. The World Food Program estimates that 11.1 million Syrians require humanitarian assistance, with 9.3 million suffering food insecurity.

A growing economic crisis is exacerbating this humanitarian disaster and is now affecting even pro-Assad Syrians who had thus far survived the war with livelihoods reasonably intact. The reason is the interconnection of the Syrian and Lebanese economies. Before the civil war and throughout most of it, Syrians had used Lebanon as a reliable place to obtain American dollars, vital for small businesses which had largely kept the economy afloat despite the conflict. Now they can’t because of the Lebanese banking crisis. That has forced Syrians to compete for scarce dollars in Syria, resulting in the precipitate fall of the Syrian currency.

In consequence, all imports, including food and medicines, have become prohibitively expensive for average Syrians. Moreover, many Syrians depend on remittances from relatives working abroad – US$2.6 billion a year, according to the World Bank—which Syrians accessed through the Lebanese banking system. No longer.

In this environment COVID-19 is subjecting Syrians across the country to another hammer blow. The number of reported infections and deaths is low—just 8,320 cases and 442 deaths as of mid-December. But this is certainly a major underestimate, reflecting limited testing.

The current chaos in Libya results from misguided NATO intervention in 2011 that went beyond the UN Security Council ‘responsibility-to-protect’ resolution that authorised it. The UK and France used the resolution to help the eastern rebel movement to topple long-term leader Muammar Gaddafi. They then effectively abandoned the country to its own devices.

The consequence was prolongation of the civil war that has split the country into three: the north-western region around the capital, Tripoli, ruled by the UN-recognised Government of National Accord (GNA); the rebel north-eastern region’s Tobruk administration, run by General Khalifa Haftar’s Libyan National Army; and the southern region, disputed by both sides, but largely controlled by local tribal leaders.

The war is currently in a relatively quiet phase following 14 months of conflict to June 2020 as the GNA beat back an assault by Haftar on Tripoli. Recent negotiations between the two sides appear to have broken down, and few doubt that fighting will resume before long.

The pandemic has hit Libya when many health facilities across the country are inoperative due to deliberate targeting during the war. Many medical professionals left the country during the years of violence.

Libya’s testing regime appears to have improved during the year, with 70,000 tests per million and 1,300 deaths currently recorded. However, the extent to which testing is uniform across the country is unclear.

Yemen has suffered for years from a combination of overpopulation (at 29 million, Yemen is the second most populous state after Saudi Arabia in the largely barren Arabian Peninsula), limited and depleting water resources, corrupt administration, and chronic tribal conflict. All of this has made it dependent on international aid and remittances from Yemenis working abroad.

As a result of Arab Spring demonstrations in early 2011, long-time authoritarian president Ali Abdullah Saleh was forced to hand over power to his deputy Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi. But Hadi’s Sunni regime struggled with the Houthi, a minority Shia sect in the north supported by Iran, which took advantage of Hadi’s weakness to declare independence, taking over the capital, Sanaa, by 2014.

Riyadh—alarmed by the Houthis’ rise, which it saw as an Iranian attempt to establish a front for anti-Saudi operations—entered the war in early 2015 with a ruthless air campaign that failed to discriminate between military and civilian targets.

On top of this, the UN has now warned that the death toll from COVID-19 in Yemen could exceed the combined toll of war, disease and hunger over the past five years. The reported number of cases is 2,083, with 606 deaths, as of mid-December. But with a reported testing rate of only 578 per million, those numbers are certainly vast underestimates.

Impact on Australia

The Middle East’s COVID-19 problem is of obvious concern to many Australians with family and friends in the region. However, of wider concern is that several Middle East states, particularly the UAE and Qatar, are transit hubs or destinations for many Australian business people or holiday makers travelling westwards. When normal travel resumes, Australians heading to Europe might be advised to avoid stopovers in the Gulf until the virus in the Middle East is fully contained.

Bleak outlook

Apart from Israel and the Gulf Arab states, the situation across the region is not likely to improve much throughout 2021. The key to moving on from the virus is widespread distribution of COVID-19 vaccines. That’s going to take time, given the MENA population is nearly half a billion.

Moreover, the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Washington estimates that about a quarter of the world’s population won’t be vaccinated until at least 2022. That’s because rich countries (including Australia) with less than 15% of the global population have reserved 51 percent of likely vaccine production over the coming year.

The wealthier Middle East states will doubtless use financial muscle to obtain early vaccine access—Bahrain, for example, is reported to have approved a Chinese-developed vaccine for use there, and the UAE is trialing it.

Poorer states, which means the majority of Middle East countries, will have to wait in line, unless China decides to provide free or subsidised supplies of its vaccine as a soft diplomacy exercise. People in states in conflict may wait a long time, given the physical danger to health workers.

The region’s economic recovery is expected to be slow. The World Bank forecast in October that economies in the MENA region would contract on average by 5.2 percent in 2020. Trade for the region is expected to have fallen by 40 percent, and remittances by nearly 20 percent.

Resumption of pre-COVID global oil demand would quickly boost Gulf Arab economies, but much will depend on widespread roll-out of the vaccine. Western tourism, the other large income and employment driver for the region, is expected to recover only slowly—even when vaccinated, Westerners may delay venturing to countries and regions where the virus is not fully controlled. Recovery of remittances in 2021 will depend on vaccination rates and economic pick-up in countries to which Middle East workers have migrated or are working.

The politics of the region remain fraught. Palestinian frustration over the breakdown in negotiations with Israel will have redoubled following recent moves by the UAE, Bahrain, Sudan and Morocco to establish diplomatic relations with Jerusalem. Prime Minister Netanyahu, who has described President Trump as the best friend Israel has ever had, may seek to announce new settlements in occupied territory before Trump’s departure on 20 January.

Trump son-in-law Jared Kushner is reported to be mediating between the GCC states to heal the rift with Qatar. It’s in Western and regional interests for the GCC to be reconstituted as an effective consultative and policy coordination body. But the differences between the opposed sides still don’t look capable of easy resolution.

Another uncertain factor is President Trump’s behaviour in his remaining days in office. Following the assassination of Iranian nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh on 27 November, apparently by Israel with Trump’s backing, there has been speculation that Trump himself may take major action against Iran – possibly ordering the bombing of Iranian nuclear program sites. He might see that as part of his legacy and one imagines he would be happy to leave the Middle East security consequences to president-elect Joe Biden.

Whether or not any of this happens, such speculation generates tension in the region, which will not assist its economic recovery.

The bottom line is that COVID-19 is likely to remain a serious worry in the Middle East for some time to come—at least a year, perhaps more. Moreover, it will exacerbate the region’s manifold problems that predated the pandemic. Even when COVID-19 is fully contained, pessimism about the region’s prospects will be justified for years to come.

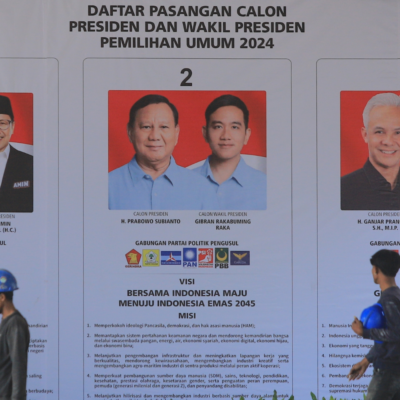

Image: Al-Kallasa, Egypt, November 2020. Credit: UN Women/Flickr