After more than 40 years of war, Taliban law—both in theory and in practice—must be under-stood on at least two levels: a formal constitutional level and a domestic political level, with the latter also acknowledging potential gaps between national and local politics. Whilst international actors seek to promote basic constitutional rights, encourage political inclusion, and support the well-being of marginalised groups (including ethnic and religious minorities as well as women), early indications suggest that, flush with a sense of outright military victory, the Taliban may be drawn towards more exclusionary forms of constitutional and legal practice.

Will the Taliban succeed in reducing international influence while, at the same time, attracting international aid and investment? Efforts to understand and engage Taliban constitutionalism and routine legal practice will require informed analysis and policy-making on several different levels at once.

Taliban constitutionalism

The Afghan Taliban are famously coy about their constitutional vision. But, already, several hints have emerged. Like constitutional drafters everywhere, the Taliban are likely to borrow from two key sources—the past and other states—although, in doing so, they will adopt a pick-and-mix approach that creates something entirely new. In short, the Taliban will borrow from others, but they will not be constrained by what they borrow.

Returning to a pattern first articulated in 1996, the Taliban have already declared their intention to draw from, while, at the same time, ‘Islamising’ the Afghan constitution introduced by the country’s last king, Zahir Shah, in 1964. Their Islamising plans are also likely to draw from internationally recognised Islamic models in several nearby states: Pakistan, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and so on. Even Qatar, seeking to reconcile the Taliban with an appreciation for women’s rights, explicitly pitched its own Islamic model as one that permits high-level education for girls. It is not yet clear how a Taliban constitution might take shape, but juxtaposing Taliban statements with models drawn from the past and neighboring states can offer several clues.

This article does not present other models as desirable. Rather, it offers a comparative constitutional perspective to place possible trends in a broader universe of ostensibly ‘Islamic’ cases.

A Pakistan proxy? No

The Afghan Taliban are often described as a Pakistan proxy, but so far there is no indication that they might draw on the complex postcolonial example set by Pakistan’s Islamic Republic: on the one hand, an elected party-based parliament with an independent judiciary and a weak head of state alongside enumerated and enforceable rights; on the other, an explicit commitment that no law will contravene the injunctions of Islam (the state religion) alongside a pattern in which the interpretation of Islam is set apart from any particular school (madhab) of Islamic legal thought (fiqh). In Pakistan, the formal legal meaning of Islam emerges from the deliberations of parliament alongside a possible review of existing statutes by a broadly independent judiciary, including a review of ‘Islamic’ matters in Pakistan’s Federal Shariat Court (Article 203C). Within that court, however, Muslim clerics (ulema) always hold a minority (203C-3A).

The Taliban however, as a clerical movement, have already rejected several elements of this model—especially, its attachment to a parliamentary form of government with a weak head of state that combines explicit fundamental rights with Islamic injunctions set apart from any particular school of fiqh. The Taliban, it seems, prefer a strong head of state—an all-powerful leader-of-the-faithful (emir-ul-momineen)—supported by an appointed (not elected) advisory council (shura) working under just one school of Sunni Muslim legal thought, namely the Hanafi school, without any enumeration of international or fundamental rights.

The Afghan constitution of 1964—cited, by the Taliban, as a key point of departure—did not combine forms of Islamic ‘establishment’ with sectarian and doctrinal ‘non-establishment.’ Instead, it highlighted just one school of Sunni thought—the Hanafi school (Article 2)—allowing Afghan judges to privilege that school wherever the constitution and existing statutes were silent (Articles 69, 102). Indeed, when so-called ‘peace talks’ with the former Afghan government led by President Ashraf Ghani began in Doha (September 2020), the Taliban explicitly insisted that any disagreement should be addressed within the terms of Hanafi jurisprudence alone.

Notwithstanding close ties to Pakistan’s military establishment, Pakistan’s constitutional approach to schools of Islamic legal thought—a rather pluralistic approach—is not one the Taliban are keen to accept.

An Iranian model? No

Departing from Pakistan, the Taliban’s state-based approach to Islam and Islamic law has more in common with the post-revolutionary constitution of Iran. That constitution privileges just one school of Shi’i fiqh—namely, the Ja’fari school—identifying that school as the official religion of Iran (Article 12) while, at the same time, specifying that no law will be permitted to contravene the core elements (usul) or injunctions (ahkam) of Ja’fari Shi’I Muslim fiqh (Article 72). Moreover, the formal legal meaning of those injunctions is not determined by a court in which clerics hold a minority; instead, it rests with clerics directly appointed by Iran’s clerical supreme leader on Iran’s constitutionally enshrined Guardian Council (Articles 4, 91, and 96). This is a model the Taliban seem more likely to favor: a strong head of state with unfettered power to appoint those who interpret just one school of fiqh.

Constitutionally, however, Iran’s hierarchy privileging a strong head of state and the Ja’fari school of Shi’i fiqh should not be understood in isolation. In particular, Iran’s constitutional emphasis on the Ja’fari school is paired with an explicit acknowledgement of ‘official status’ for several other schools of fiqh, including the Sunni Hanafi school (Article 12). At the same time, Iran’s constitution formally recognises Christian, Jewish, and Zoroastrian religious minorities, allowing each ‘to act according to [its] own canon in matters of personal affairs’ (Article 13). The same is true in Brunei, where the official religion is defined as Islam ‘according to the Shafeite sect of Ahlis Sunnah Waljamaah,’ that is, the Shafi’i school of Sunni fiqh (Part I, Article 2-1), even as ‘all other religions may be practiced in peace and harmony’ (Part II, Article 3-1). In 1964, even the constitution of Afghanistan acknowledged that non-Muslims would be free to perform their religious rituals (Article 2); and, in 2004, Afghanistan’s default preference for Hanafi fiqh (Article 130) was paired with explicit recognition for Shi’i personal law (Article 131).

It is extremely unusual to combine broadly ‘Islamic’ with more particular ‘fiqh-based’ forms of constitutional religious establishment. But, even where this occurs—for example in Iran, Brunei, and Afghanistan after 1964—such combinations are not expressed in strictly exclusionary terms. There is, in fact, no constitution in the world with anything like the strictly exclusionary Hanafi-only approach the Taliban seem to prefer. Constitutional drafters routinely stress the importance of a ‘local’ constitutional imprimatur. But, like constitutional drafters everywhere, the Taliban may embrace an ‘Afghan’ model without being confined to Afghan models from the past.

Clerical and coercive power

The Taliban are associated with the so-called ‘Deobandi’ tradition of Hanafi Sunni Islam, which emerged during the late-nineteenth century in the town of Deoband, India. But again, even as the Taliban borrow from the Deobandi tradition, they simultaneously depart from it, particularly when it comes to their ideas about the link between ‘religious’ and ‘executive’ forms of power.

In Deoband, clerics stress advisory forms of religious power, leaving executive forms of power (involving coercive patterns of enforcement) to those associated with the state. In many ways, Deobandi clerics see advisory forms of power as ‘authoritative’ whilst criticising coercive forms of non-clerical state power as inclined towards ‘authoritarianism.’

But, in Afghanistan, the Taliban have turned this Deobandi tradition upside down, seeking to combine clerical and state-based forms of power while, at the same time, rejecting models of religious and executive power based in other parts of the Muslim world where religious and electoral or monarchical forms of power often work hand-in-hand.

Rejecting the notion of an Islamic republic (as in Pakistan, Iran, or Afghanistan after 2004), for instance, the Taliban have downplayed any attachment to electoral politics rooted in universal adult suffrage. Yet, pulling away from Muslim-majority states in which clerical and monarchical forms of power work together—for example, Saudi Arabia—the Taliban are also keen to replace the monarchical order of Afghanistan under King Zahir Shah (1964) with a clerical order led by their own emir-ul-momineen, Mullah Haibatullah Akhundzada. Situated somewhere in between Iran and Saudi Arabia, the Taliban seem likely to construct a new relationship between clerical and coercive power: as in Iran, an all-powerful clerical leader with quasi-monarchical powers but, as in Saudi Arabia, few of the constraints associated with politically relevant elections.

Rejecting both electoral and monarchical power, the Taliban have indicated that their all-powerful clerical emir will be supported by an advisory council (shura) he appoints. This advisory council will not resemble the strictly advisory Council of Islamic Ideology appointed by Pakistan’s president (Article 228): that council, with a mix of clerics and non-clerics (as well as at least one woman) is required to reflect several different schools of Islamic legal thought. In Afghanistan, the Taliban’s advisory council is more likely to resemble the all-male, Ja’fari-only, clerical half of Iran’s well-known Guardian Council. That half is directly appointed by Iran’s supreme leader, whereas the other half, composed of non-clerical jurists, is appointed by Iran’s elected parliament on the basis of a list drawn up by Iran’s chief justice. (Iran’s chief justice is also appointed by the country’s supreme leader.) Clearly, under the Taliban, any process involving an elected parliament is unlikely. Instead, the Taliban’s emir-ul-momineen is likely to appoint his own advisors directly.

Again, the Taliban are likely to borrow constitutional elements from the Afghan past as well as other Muslim states. But, in doing so, their constitutional thinking will not mirror that of Afghanistan (1964), Pakistan (1973), Iran (1979), or Saudi Arabia (1992). Seeking to consolidate their power after more than 40 years of war, they are likely to borrow quite selectively, institutionalising a strictly advisory council under a quasi-monarchical clerical emir, unfettered by substantial electoral constraints, with far-reaching powers to articulate his own understanding of Hanafi-only Sunni fiqh. This constitutional vision is historically unique. It is not merely set apart from the constitutional architecture of the international forces who fought the Taliban. It is also at odds with prevailing notions of religious diversity, political accountability, and ‘Islamic’ constitutionalism across the Muslim world.

Taliban constitutionalism in practice

Like Frankenstein’s monster, Taliban constitutionalism will be cobbled together, in its own historical context, from many disparate parts. At the same time, however, it is also likely to remain ‘a dead letter’ until it is brought to life on two levels: an elite (national) level and a non-elite (local) level. Understanding Taliban constitutionalism in practice—that is, historically embedded forms of Taliban governance—will require an appreciation for political patterns unfolding on these two different levels.

The national level

At a national level, much attention has been paid to the composition of the Taliban’s so-called ‘interim’ cabinet—in effect, the cabinet convened under Taliban emir Mullah Haibatullah Akhundzada and charged with breathing ‘life’ into the Taliban regime until prevailing conditions allow for the organisation of a national convention (loya jirga) to endorse Akhundzada, his government, and a new Afghan Taliban constitution. This interim cabinet must be understood, first and foremost, in the context of Taliban efforts, after four decades of near-constant war, to secure and consolidate their power.

The Taliban’s interim cabinet is characterised, first, by an all-male cohort of Taliban sympathisers and, second, by an overwhelming Pashtun ethnic bias that leaves almost no room for ethnic minorities. Indeed, even the addition of pro-Taliban Tajik, Uzbek, and Hazara Shi’i members has failed to suggest anything like the ‘inclusive’ approach to ethnic, religious, or political coalition-building the U.S., the E.U., Iran, Russia, China, and multiple Central Asian states have sought to encourage. Beyond this pattern of ethnic and gender-based exclusion, however, particular attention has been paid to the cabinet’s focus on ‘hardline’ Taliban over so-called ‘moderate’ views. The Taliban seem to believe that inclusionary governance will be less stable than an exclusionary focus on regime consolidation. It is this intra-Taliban calculation that, in the short term, will most directly impact Afghan constitutionalism and governance.

Briefly, political moderates like Deputy Prime Minister Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar and Deputy Foreign Minister Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanekzai have been placed in subordinate (‘deputy’) positions whilst security-sector hardliners like Interior Minister Sirajuddin Haqqani and Defense Minister Mullah Yaqoob have been elevated. (All four remain on UN sanctions lists.) In fact, no matter what sort of ‘Frankenstein’ constitution might be cobbled together on paper, the life of that constitution—its operationalisation at the level of practical governance—will hinge on the relative influence of what might be described as a moderate Taliban ‘Dr. Jekyll’ and a hardline security-sector ‘Mr. Hyde’.

So-called ‘peace talks’ bringing the Afghan Taliban together with the former Afghan government led by President Ashraf Ghani in Doha sought to draw out inclusionary moderates. But, even in Doha, these political moderates were thwarted by military hardliners; and, bolstered by U.S. President Donald Trump’s promise of a firm date for the withdrawal U.S. troops, these hardliners refused to engage in any serious negotiations until all of the international troops supporting Ghani (and his army) had left. Today, many states remain hopeful that Taliban governance might turn towards moderation—in fact, beyond humanitarian aid, offers of future funding for development assistance and regional trade or infrastructure expansion are often cast as a type of external leverage that might tilt the Taliban towards moderation. But, so far, reflecting a tangible focus on domestic regime consolidation over new forms of international engagement, this tilt has not occurred.

Externally, ‘moderation’ is often defined in terms of some appreciation for the well-being of women as well as ethnic and linguistic minorities—if not with reference to an explicit defence of human rights, given Taliban efforts to set themselves apart from external legal norms, then at least with reference to an inclusive reading of traditional Islamic sources. Moderation is also defined, perhaps first and foremost, in terms of a perceived willingness to constrain erstwhile jihadi allies in transnational groups like the East Turkestan Islamic Movement a.k.a. the Turkestan Islamic Party or TIP (targeting western China), the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan or IMU (targeting Central Asia), the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan or TTP (targeting Pakistan), and al-Qaeda. Specifically, international powers expect Taliban ‘moderates’ to move beyond operational constraints on transnational jihadis towards a complete elimination of core ideo-logical ties.

External funding-focused efforts to tilt the political scales towards moderation and away from Taliban hardliners are generally associated with otherwise-competing global powers like the United States and China or the European Union and Russia. But these efforts are also supported by otherwise-competing Muslim leaders in states such as Iran and Saudi Arabia. Global powers fear that, as on 9/11, militant safe havens protected by Taliban hardliners could shelter jihadi groups planning attacks abroad. Saudi Arabia fears that hardliners might leave space for groups like al-Qaeda to nurture and export their opposition to monarchical rule. Iran fears hardline expressions of Sunni supremacy (versus the Shi’a). In fact, even beyond these states, Muslim-majority leaders from Bangladesh to Indonesia fear that Taliban hardliners might inspire local militants who pose a threat to their rule. Again, building on decades of international economic engagement, even dependency, calibrated forms of financial assistance are often seen as a type of external leverage that might help to shape (or re-shape) the internal political calculations of the Taliban.

Returning to a domestic political focus on regime consolidation, however, the composition of the Taliban’s interim cabinet—and, following on from this, the Taliban’s approach to Afghan governance—appears to downplay the importance of ‘international’ legitimacy in favour of hardline ‘jihadi’ legitimacy.

Domestically, this tilt away from moderates towards hardliners is often explained in terms of internal Taliban efforts to reduce the risk of defections—specifically, defections toward even more hardline ideological rivals like Islamic State or Daesh. (The Afghanistan branch of Daesh is also known as the Islamic State Khorasan Province or, simply, I.S.K.) Briefly, I.S.K. opposes any territorially bounded nationalist movement that might appear to accommodate so-called heretics: for I.S.K., this includes (inter alia) Afghan Shi’a and unveiled/unaccompanied women. So, to outflank any domestic political threat from I.S.K., Taliban hardliners seem keen to avoid any:

- rhetorical reference to territorially bounded Afghan nationalism (like previous Afghan regimes, the Taliban have hesitated to acknowledge the Durand Line as a legitimate Afghanistan-Pakistan border)

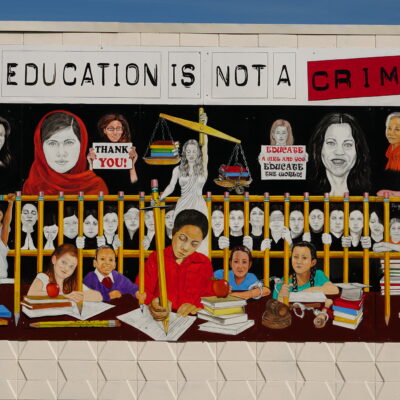

- significant push to promote employment or higher education for unveiled/unaccompanied women and girls

- substantial push for sectarian inclusion (for example, constitutional recognition for the Shi’a),and

- security-oriented cooperation with external powers like the U.S. (in October, the Taliban rejected any security collaboration with the U.S., even in the context of a joint effort to defeat or destroy I.S.K.).

Even if, bowing to international pressure, a Taliban constitution could be brought to life at a national level by a moderate, inclusive, Taliban ‘Dr. Jekyll’, enduring forms of intra-jihadi competition seem likely to ensure that, for the time being, Taliban governance will be animated by a hardline, exclusionary, Taliban ‘Mr. Hyde’. Indeed, even apart from recent statements calling for a resumption of punitive amputations by former Taliban Justice Minister Mullah Nooruddin Turabi (now the Taliban’s Acting Minister for Prisons), this intra-Taliban political dynamic, at a national level, clearly helps to contextualise the revival of hardline punishments in cities like Herat (80 miles east of the Iranian border), where, in a bid to consolidate their authority—moving away from international legal norms while, at the same time, countering a powerful domestic challenge from I.S.K.—Taliban officials have already resumed the public display of executed and mutilated corpses.

The local level

At a national level, the operationalisation of Islamic governance under the Taliban remains heavily skewed towards hardliners. And yet, even if coordinated forms of international pressure were to tip the political calculations of the Taliban’s emir-ul-momineen, Mullah Akhundzada, away from powerful hardliners, it is worth recalling that, in Afghanistan, the state is notoriously weak. Indeed, pulling away from the external narratives and top-down directives that often frame national politics in Afghanistan, it bears asking what Taliban governance might look like on the ground. Specifically, turning to a grassroots understanding of Islamic law, it bears recalling a famous expression that was taken up and elaborated by the German sociologist Max Weber: ‘kadijustiz’ or ‘qadi justice’.

Far from any predictable, ahistorical, fixed, or even ‘strict’ form of law, Weber noted that religious law at a local level is often historically idiosyncratic or arbitrary. This description—what Harvard Law School Professor Intisar Rabb has described as an account of ‘justice without law; substance without procedure’—is often dismissed by scholars with an appreciation for sophisticated patterns of Islamic jurisprudence or fiqh. But, at a local level, in Afghanistan, Weber’s description is often more difficult to set aside, particularly in light of the ways in which relatively autonomous Taliban commanders, responding to grassroots appeals for ‘speedy justice’ from those aggrieved by external or more highly centralised forms of law, have tended to exercise their interpretive/normative discretion within largely unfettered forms of judicial-cum-executive power.

In Afghanistan, references to Islamic law are ubiquitous, but the degree of variation at the local level is enormous, particularly with reference to the rights of women, the rights of ethnic and religious minorities, and general rights pertaining to wide-ranging institutions like the press. While the Taliban Minister for Higher Education stated that veiled women would be free to attend gender-segregated university classrooms, for instance, questions emerged after the Taliban’s new chancellor of Kabul University was reported to bar female students altogether. That report was later retracted; but, in the meantime, returning to the notion of kadijustiz, the Taliban’s Deputy Minister of Information and Culture said that the chancellor’s reported decision was a matter of his ‘personal view’. In August, Taliban commanders in Kabul protected local Shi’a as they marched to commemorate the day of Ashura (the death anniversary of Imam Hussein). But, in the central Afghan province of Daykundi, 13 Hazara Shi’a were killed. And, in neighbouring Bamyan, the statue of a Hazara Shi’a militia leader previously killed by the Taliban was destroyed. Finally, in September, the Taliban issued 11 new rules pressing journalists to work ‘within the limits of Islam’. Elaborating, a spokesman for the Taliban Ministry of Foreign Affairs simply noted that journalists should not ‘cross certain bounds’. Needless to say, Afghan journalists described these guidelines as vague. Many complained that they would almost certainly permit arbitrary patterns of Taliban enforcement on the ground.

Conclusion

In Afghanistan, Taliban constitutionalism is likely to draw on constitutional models from across the Muslim world. But, in practice, after more than 40 years of war, much will depend on the ways in which those models are brought to life by Taliban leaders focused on consolidating their power. At a national level, intra-jihadi competition is likely to ensure a prominent role for Taliban hardliners. But, as the Taliban themselves revealed in their own successful push to peel defectors away from the Afghan National Army before seizing power in Kabul, the authority of any ‘national’ regime is often closely tied to the work of its ‘local’ commanders. In 2020, many Americans noticed that their country’s constitutional architecture rested rather precariously on the idiosyncratic actions of key officials—not only at a national level, where Republican moderates found themselves marginalised by right-wing hardliners, but also at a local level, where several important office-holders seemed to interpret laws in light of their ‘personal choice’. In Afghanistan, so far removed from the U.S. experience, the outlook is also quite precarious. An historically embedded reading of comparative constitutionalism will undoubtedly illuminate key aspects of Taliban governance. But, at a local level, we may find that formal references to Islamic constitutionalism remain as long as a piece of string.

Image: Aerial View of Kandahar City. Credit: Flickr/Afgbeast.