At the 38th ASEAN Summit in October 2021, ASEAN leaders released a ‘Declaration on Upholding Multilateralism’. Describing the value of multilateralism in terms of its ‘rules-based nature, inclusivity, transparency and openness’, the declaration called for the strengthening of ASEAN-led institutions and ASEAN centrality. Although the nature and contents of the declaration were largely uncontroversial, the fact that ASEAN—or rather, last year’s Brunei chair—saw a need to issue such a declaration suggests a concern with recent trends in the regional security architecture and what they meant for the 54-year-old organisation.

This article seeks to unpack these trends, examine their implications for ASEAN and the region at large, and suggest how regional security multilateralism will evolve.

Although the declaration on multilateralism had been in the works for some time before the ASEAN Summit, the timing of its official release came about a month after the surprise announcement of the Australia-United Kingdom-United States (AUKUS) security pact. The announcement of the trilateral partnership prompted a diversity of views, including warnings that Australia’s purchase of nuclear-powered submarines under the deal could trigger a nuclear arms race in the region. Other views were supportive of the new arrangement and highlighted the role of AUKUS within the broader geopolitics.

Some observers also noted the potential impact that AUKUS could have on ASEAN and its much-vaunted centrality in the regional security architecture. Certainly, AUKUS is not the first—and will likely not be the last—minilateral arrangement to spark debate about the longevity of ASEAN’s role as the hub and convenor of regional multilateralism. Nevertheless, seen in this context, the timing of ASEAN’s declaration on multilateralism could be regarded as the Association’s attempt to underscore the relevance of its brand of inclusive multilateralism amid the growth of minilateral and non-ASEAN-centred arrangements in the regional architecture.

Challenges

ASEAN’s call to uphold multilateralism—more specifically, ASEAN-led multilateralism—is arguably a response to several key trends that have characterised regional dynamics in recent times.

The first and most overarching of these trends is Sino-U.S. rivalry; not just its intensification, but also that it is becoming a permanent condition of international politics. In May 2021, U.S. National Security Council’s Coordinator for Indo-Pacific Affairs Kurt Campbell said that the ‘dominant paradigm’ governing U.S. policy towards China would be competition, albeit ‘a stable, peaceful competition’. The extent to which major power competition is ‘stable’ and ‘peaceful’, however, depends very much on whose perspective is being sought.

For the smaller Southeast Asian countries that rely heavily on a stable external environment and the maintenance of good relations with both major powers for economic growth and survival, the expansion of Sino-U.S. competition across many sectors of global affairs is not reassuring. Beijing and Washington are not only vying for leadership in the areas of economics, infrastructure, military, and science and technology, they are also pursuing competing visions of the regional order in the Asia Pacific.

China, which had traditionally deemed the ASEAN Plus Three as the most appropriate multilateral framework in the region, unveiled its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013 to strengthen connectivity and integration across Asia, Europe and Africa. An official document outlining the BRI concept highlighted that ‘as the largest developing country and the world’s second largest economy’, China is seeking to bear ‘its wider responsibilities in promoting international economic governance toward a fair, just and rational system’.

Concerns about the BRI have revolved around the leverage that China would be able to gain over BRI member countries through its investments and economic assistance, which could subsequently sway their foreign policies. While acknowledging that reactions towards the BRI are characterised by complexity, the close linkages between economics and politics have certainly been brought into sharp relief. Even before the BRI was launched in 2013, China’s growing influence was already fanning discussions about the implications for Southeast Asian countries and ASEAN.

The impact of such dynamics on ASEAN could also be seen in the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC) framework. As one analyst observes, the LMC is the ‘first Chinese-built Southeast Asian institution’ and demonstrates Beijing’s attempt to seek regional leadership. In contrast to China’s prioritisation of the Mekong sub-region, ASEAN has been slow to shed its ‘bystander’ status in Mekong issues even though the river runs through five of its member states. This has prompted worries that Sino-U.S. competition in the Mekong sub-region would contribute towards the erosion of ASEAN unity and consequently its central role in the broader region.

Meanwhile, the U.S. has put forward its Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) strategy. The strategy was launched by the Donald Trump administration but has continued to be the main framework guiding President Joe Biden’s regional policy. In a speech during his visit to Jakarta in December 2021, Secretary of State Anthony Blinken described a ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’ as being ‘free from coercion and accessible to all’, where ‘problems will be dealt with openly, rules will be reached transparently and applied fairly, goods and ideas and people will flow freely across land, cyberspace, and the open seas’.

Supported by U.S. allies and partners, the FOIP strategy is associated with initiatives such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad), AUKUS, Blue Dot Network (an American led initiative on infrastructure investment), and the stepped-up Mekong-U.S. Partnership which aims to promote sub-regional cooperation. While these initiatives are regarded by the United States and its like-minded partners as useful ways to limit rising Chinese influence in the region and provide public goods, the speed at which such arrangements have taken hold over the past few years is a cause of concern for ASEAN.

Since the early 1990s, ASEAN has established its central role in the regional security architecture. It took the lead in inaugurating the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF), East Asia Summit (EAS) and ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting-Plus (ADMM-Plus) and continues to assume an agenda-setting and convening role in regional multilateralism that engages the major and regional powers. ASEAN’s dialogue partners have generally been supportive of ASEAN centrality in the regional architecture. Given that this support for ASEAN continues to be expressed in the rhetoric of Washington and its like-minded counterparts, it may seem alarmist to warn of the demise of ASEAN centrality.

Yet, at the rate that new, more exclusive, non-ASEAN arrangements are developing, it is not too farfetched to point out the scenario that the broad and inclusive model of multilateralism typically espoused by ASEAN may gradually slide into irrelevance.

This is especially so if we consider the developments surrounding multilateralism, especially under the former Trump administration. During his presidency, Trump never attended a full East Asia Summit. Admittedly, the Biden administration has taken action to reverse this trend. Biden attended his first East Asia Summit as president in October 2021, along with the ASEAN-U.S. Summit where he pledged up to US$102 million to support the ASEAN-U.S. Strategic Partnership. These are undoubtedly encouraging signs to ASEAN and its member states, particularly when compared to the Trump administration’s visible neglect.

The crux of the matter, however, is that (re)engaging ASEAN is merely one of several strategies pursued by Washington to bolster its influence in the region. Another strategy, as highlighted above, would be the establishment of new mini- or multilateral arrangements centred on the United States and its allies. ASEAN’s call to uphold inclusive multilateralism could thus be read as a response to the formation of these more exclusive networks among like-minded partners.

Internally, ASEAN is also facing several key challenges that are putting pressure on its model of multilateralism. One of these challenges involves the dynamics in the Mekong sub-region, which, as earlier mentioned, is starting to become entangled with major power rivalry. Other pressing conundrums for ASEAN include the Myanmar political crisis and the South China Sea disputes. In all these issues, ASEAN has come under fire for its slow progress. These criticisms have arisen not just from external sources, but from some of its own member states.

To be fair, ASEAN’s decision not to invite Min Aung Hlaing, the Myanmar military leader, to the series of summits in October 2021 illustrated a rare tough stance against the junta. As an analyst observed, the decision also implicitly reflected the value of ASEAN; —had ASEAN not expanded to include the mainland Southeast Asian states in the 1990s, it would not have been able to exercise as much influence over the current political crisis. The fact remains, however, that little concrete progress has been made regarding ASEAN’s Five-Point Consensus which was agreed upon in April 2021.

These issued-based challenges speaks to a broader concern about the perceived lack of leadership in ASEAN, a criticism which Malaysian Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah has raised. Indonesia, traditionally regarded as ASEAN’s de facto leader, has appeared to withdraw from such a role under the Joko Widodo administration—although it has sought to regain its leadership in ASEAN’s response towards the Myanmar crisis. The expectation is that without strong leadership, ASEAN’s brand of multilateralism is likely to falter.

These internal and external developments thus pose challenges to ASEAN’s cohesion and central role in the region, and consequently its approach of a broad-based regional multilateralism. It would, however, be unwarranted to say that ASEAN has not been able to advance regional cooperation through its inclusive model in recent times.

Preservation

At its core, ASEAN continues to offer a one-of-its-kind platform for all the key stakeholders in the region to engage with one another. This remains ASEAN’s unique value, even amid the establishment of other non-ASEAN-led platforms.

ASEAN’s inclusive multilateralism is particularly important for regional norms and rules building. When it comes to emerging challenges, such as cybersecurity, artificial intelligence and chemical, biological and radiological (CBR) security, ASEAN has a role to play in moving regional players towards a consensus on norms and standards. Given that these are relatively new areas of non-traditional security, there exists an opportunity for ASEAN to take the lead in driving the regional approach in these issues.

For example, the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting has taken several steps to strengthen cooperation on cybersecurity, including setting up an ASEAN Cyber Defence Network and a Cybersecurity and Information Centre of Excellence. ASEAN has also sought to extend cybersecurity cooperation to its dialogue partners, such as through the ADMM-Plus Experts’ Working Group on Cyber Security and the ASEAN Regional Forum Inter-Sessional Meeting on Security of and in the Use of Information and Communications Technologies.

While there would undoubtedly be difficulties in getting to a common position on such issues, ASEAN’s traditional attributes as a neutral and non-threatening convenor are expected to serve it well in its efforts to usher regional countries, including the major powers, towards some sort of agreement in establishing behavioural norms.

To be sure, ASEAN’s value is not merely based on what it does; much of the assessment of ASEAN’s usefulness, in this current climate, also depends on how the non-ASEAN countries perceive and respond to the Association. The good news for ASEAN is that thus far, non-ASEAN countries continue to appear interested in engaging with it.

The United Kingdom, for instance, became ASEAN’s newest dialogue partner in August 2021, and has sought—along with others such as France and Canada—to engage with ASEAN-led mechanisms such as the ADMM-Plus and EAS. Later in 2021, ASEAN-Australia and ASEAN-China ties were elevated to the level of ‘Comprehensive Strategic Partnership’, indicating a mutual interest to deepen cooperation in both sets of relations.

Australia and South Korea additionally held their first-ever defence ministers’ informal meetings with ASEAN in 2020 and 2021, respectively. These are in addition to similar meetings that ASEAN already holds with China, Japan and the United States. Moreover, ASEAN conducted its inaugural naval exercise with Russia in December 2021, following its maritime exercises with China in 2018 and with the United States in 2019.

It is clear that ASEAN persists in its pursuit of inclusive regional multilateralism, and that non-ASEAN countries are likewise keen to maintain engagement with ASEAN in security and defence. In fact, a key focus area for ASEAN is now on managing the interest from non-ASEAN partners, as indicated by guidelines adopted by the ADMM in 2021 on how to ‘assess, evaluate, and respond to requests or proposals regarding engagements with ASEAN’s external partners’.

Even in cases where such engagement remains relatively superficial, the interest shown in ASEAN is likely to provide a useful basis upon which the Association could further highlight its regional relevance. It will be a delicate balance between keeping the non-ASEAN countries keen to maintain relations with ASEAN and ensuring that such interest does not overwhelm the Association to the extent that cooperation becomes unwieldy and cumbersome. The latter scenario would reinforce perceptions that ASEAN is slow to make progress on regional matters of concern.

Co-existence

Given that ASEAN continues to serve a useful role in regional security multilateralism despite the internal and external challenges it faces and taking into account the growth of non-ASEAN-led arrangements, we could extrapolate several key elements of how regional security multilateralism may evolve going forward.

The regional multilateral architecture is likely to become more multi-layered, with more networks overlapping one another in membership and agenda. Regional powers, such as Australia, India and Japan, are expected to feature more prominently in institution building as they seek to both continue engaging with inclusive ASEAN-led platforms as well as join or initiate new arrangements that primarily involve their like-minded partners.

Major powers, such as China and the United States, are similarly expected to continue to maintain close relations with ASEAN if only for the purpose of exercising their respective influence over the region, regardless of their genuine belief about the viability of ASEAN’s model of multilateralism. Engaging with ASEAN is, after all, a relatively low-cost way to demonstrate their commitment to the region. Nevertheless, Beijing and Washington are likely to continue investing in other networks that contribute towards bolstering their regional leadership and dominance. This also means stronger links among U.S. allies and partners, and likewise for China’s regional partners.

ASEAN will, in all likelihood, retain its value as a regional platform for broad and inclusive multilateralism. In ASEAN-led mechanisms, the Association’s importance will stem from its provision of inclusive dialogue platforms, as well as its ability to garner agreement on norms in emerging security challenges. Such endeavours may result in relatively broad and perceptibly underwhelming outcomes, but the point is that ASEAN, for now, remains the only regional actor that could garner buy-in from all the regional players on its agenda.

For instance, amid the contesting visions of the regional order, the Association demonstrated agency in responding to external developments by issuing the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP), which called for strengthening and revitalising ASEAN-led arrangements. In its usual custom of inclusivity, ASEAN has also secured the support of its dialogue partners, including China and the United States, for AOIP principles and cooperation. Some critics have charged that the AOIP offers little in terms of concrete measures, but that does not negate its value of encapsulating a vision of the regional order that is acceptable to both major powers.

The interest of extra-regional partners in ASEAN-led platforms is also anticipated to continue for the foreseeable future, in light of ASEAN’s distinct functions in the region. Even if only symbolic, the perception of ASEAN’s importance would certainly help rather than harm the organisation. Moreover, while ASEAN would welcome such extra-regional interest in the spirit of openness and inclusivity, it is likely that the Association will try to keep the level of extra-regional interest at a manageable level.

Consequently, it is likely that ASEAN will approach its relations based on three concentric circles. The first circle, which comprises ASEAN member states, would be the foundation upon which ASEAN could strengthen its regional credentials; the second circle would comprise the dialogue partners and more pertinently, the countries in the East Asia Summit and ADMM-Plus; and, the third circle would consist of countries with which ASEAN is keen to engage but without the formal status of a full dialogue partner.

In such a scenario—which, frankly, is not an unfamiliar setting—ASEAN-led arrangements and non-ASEAN-led networks would co-exist. They may overlap in membership composition and focus areas, but would ultimately serve different functions and represent different forms of regional security cooperation. In this sense, ASEAN-led and non-ASEAN-led platforms could conceivably complement each other and collectively contribute towards a more effective regional architecture in the longer term.

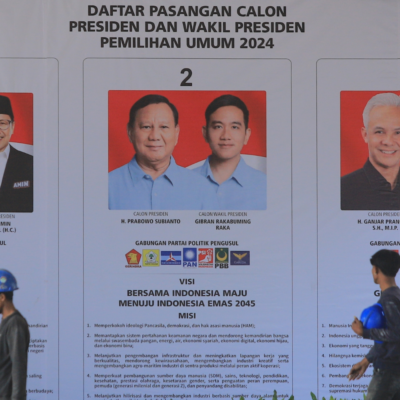

Image: ASEAN flags, ASEAN-Australia Leaders Plenary Opening Remarks, Sydney, 2018. Credit: ASEANinAus/Flickr.