The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed some of the weakest links in Australian society in relation to race relations and communications.

Culturally and linguistically diverse communities and people with recent immigrant backgrounds in Australia had particular challenges gaining relevant information about COVID-19 and communicating with government authorities in the time of a global health crisis. People perceived to be ‘Asian’, especially those wearing face masks, were suspected of being carriers of the virus and verbally and physically abused in public spaces. In April 2020, the Prime Minister Scott Morrison told temporary migrants and international students to go home.

Through a national survey conducted in October 2020, we explore the sources that Asian Australian communities used to access information about COVID-19 in Australia, the extent to which they trust those information sources, and potential factors explaining the results.

The survey

We surveyed 432 adults in Australia who self-identify as Asians or Asian Australians, including a wide range of residents in Australia with Asian heritage. A total of 878 individuals accessed the survey questionnaire, of which 432 (49 percent) provided usable responses after screening and quality checks. The final sample consisted of slightly more female respondents (54.2 percent) than male, 55.1 percent were aged 49 or younger, and 80.1 percent were born outside Australia. Almost 30 percent (29.9 percent) identified themselves as Chinese and 22.7 percent identified themselves as Indian. A majority (67.8 percent) had at least a Bachelor’s degree, and the median annual household income (before tax) was in $75,000-$99,000.

Traditional media was the most sought-after source

Traditional media such as newspapers, television and radio were the most sought-after sources of COVID-19 information in general (Mean Score (M) = 3.73 out of 5, Standard Deviation (SD) = .99), followed by government authorities (M = 3.60, SD = .98) or Internet media such as health websites, forums, or blogs (M = 3.60, SD = 1.02). To our surprise, social media such as Facebook or Twitter (M = 3.10, SD = 1.22) were the least utilised source of information.[1]

When it comes to trust in the information sources [2], information from healthcare providers (M = 4.30, SD = .73) was perceived to be the most reliable, followed by government authorities (M = 4.21, SD = .77). Social media was seen as the least reliable source (M = 3.10, SD = 1.06). Traditional media was in-between (M = 3.73, SD = .84).

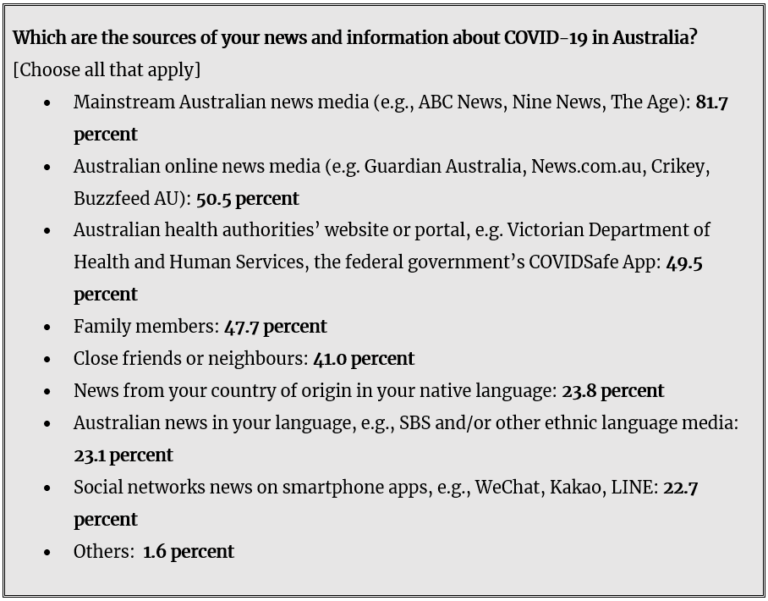

When respondents sought information particularly about the pandemic situation in Australia, again the traditional mainstream media were the most widely used source (81.7 percent). Ethnic language providers such as SBS (23.1 percent) or news from countries of origin (23.8 percent) were among the least consulted sources. Perhaps this was related to the fact that most respondents said they spoke English competently—61.8 percent ‘very well’ and 37.3 percent ‘well’—and most had lived in Australia for at least several years (63 percent of respondents born outside Australia arrived before 2011). However, the low use of ethnic language news sources may indicate something about their utility and, to a certain extent, the perceived quality of those sources.

A particularly significant finding is that more than four out of 10 respondents sourced COVID-19 information from their family members (47.7 percent) or close friends or neighbours (41 percent). This shows that families and close friends played a significant role in information acquisition and distribution. It was unclear from our research what the main sources of information were within family and friends. There is evidence that migrants’ social networks are particularly important generally in terms of being trusted and relied upon. It is often the distributors of critical information who facilitate movements and settlement of migrants.

High trust in government and low trust in ethnic community associations

When it comes to the most trustworthy sources of news about COVID-19 policies in Australia,[3] our respondents ranked government websites (M = 4.18, SD = .84) as sources on which they are most likely to rely for accurate information, followed by news sites (M = 3.65, SD = .78) and families and friends (M = 3.59, SD = .84).

Trust levels in government sources were very high—assessed by respondents as 4.18 out of five. Trust was far lower in ethnic community associations at M = 2.88 (SD = 1.01). Respondents did not seem to trust their co-ethnic communities as much as they do sources on social media or news sites.

As pointed out above, multilingual ethnic language services were not much used by respondents. Only 22 percent used the government-funded multilingual resources, mostly distributed through ethnic resident association and community leaders.

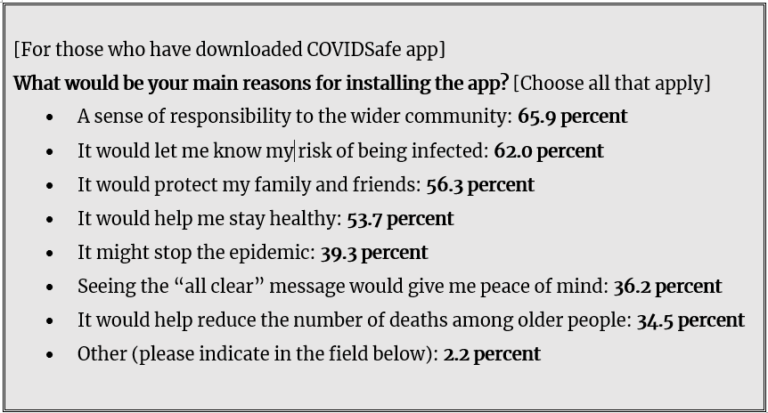

The federal government’s COVIDSafe contact tracing app, was downloaded by 53 percent of respondents. This suggests that Asian communities were more likely to download the app than the general public—it has been downloaded by approximately 40 percent of the population who could use the app on their smartphones. ‘A sense of responsibility to the wider community’ was the reason for downloading the app nominated by 65.9 percent of respondents, among other reasons. This was slightly higher than more individualistic motivations such as ‘letting me know of my risk’ (62 percent) or ‘helping me stay healthy’ (53.7 percent).

Public health was prioritised over individual rights such as privacy

One of the most interesting findings from our survey was how much Asian Australian communities value public health over human rights.

When asked to indicate the degree to which they agree with the statement ‘Protecting public health comes before individual privacy and human rights’, 69 percent of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed with the statement. Only 5.5 percent stated they disagreed or strongly disagreed. The mean score was 3.81 (SD = .87) on a 5-point Likert scale anchored on 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’ to 5 = ‘Strongly agree’.

Established immigrants compared with new immigrants

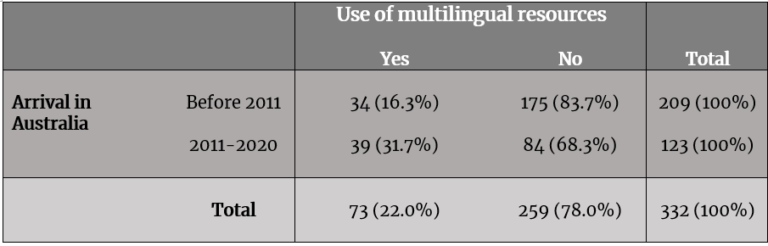

We conducted a further analysis on a subset of the respondents: immigrants (N = 332), in other words, those who reported that they were born outside Australia and indicated the year they had arrived in Australia. We performed a Chi-square test of independence (a statistical test to determine a significant association between two nominal variables) to examine the relationship between immigration years (those who arrived in Australia before 2011 and those who arrived after 2011) and the use of multilingual resources provided by the government, to understand more about pandemic communication behaviour among Asian Australian communities.

The relationship between these variables was significant. Those who arrived in Australia in 2011-2020 were more likely than those who arrived in Australia before 2011 to use multilingual resources (X2 (1, N = 332) = 10.76, p < .01).

Table 1. Use of multilingual resources by arrival year (number of cases(percentage))

%: Within years arrived in Australia

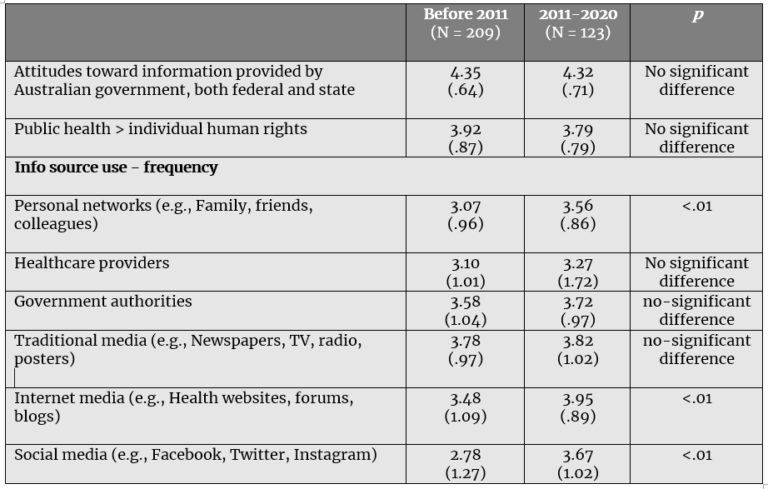

We further performed a series of independent t-tests (an inferential statistical test to determine a statistically significant difference between the means in two unrelated groups) to see the relationship between immigration years (two categories of those who arrived in the last 10 years, in other words, before and after 2011) and several continuous variables examined in this study. Surprisingly, there was no difference between the two immigration year groups in terms of the attitude toward information provided by the government and the perceived importance of public health versus individual human rights.

Recent immigrants (2011-2020) were more likely than their more established counterparts (before 2011) to rely on personal networks, internet media, and social media to seek information about COVID-19.

Table 2. Mean comparisons (independent t-test) (Mean (standard deviation))

Conclusion

Our preliminary survey of 432 adults in Australia who self-identify as Asian indicates that:

- the majority think public health should be prioritised over individual rights and privacy

- they place high trust in government

- the most used sources of information in relation to COVID-19 in general are traditional news media such as TV or newspapers

One of the determining factors for these results is the length of residence in Australia: immigrants within the last 10 years tend to rely more on personal networks, the Internet and social media for information on COVID-19.

We also find that not many Asian Australian communities are using multilingual services, in which governments have invested considerable resources.

In policy terms, governments can be confident about having gained a high level of trust from Asian Australian communities in spite of the negative perceptions of them displayed by some political leaders, individuals and the media. However, governments should examine the utility of multilingual information resources that need to be more relevant and culturally sensitive.

Traditional media are the most used source of COVID-19 information among Asian communities in Australia. Authorities should therefore be vigilant in relation to misleading media reportage of critical health information. Effective communications across different ethnic groups are key to maintaining a cohesive and healthy society.

[1] Measured on 5-point scales anchored on 1 = “Never” to 5 = “All the time”

[2] Measured on 5-point scales anchored on 1 = “Not trust at all” to 5 = “Trust a lot.”

[3] Measured on 5-point scales anchored on 1 = “Very unlikely” to 5 = “Very likely”

Authors: Dr Wonsun Shin and Dr Jay Song

The survey was conducted with generous funding from the Academy of Korean Studies (Project Number: 033378). The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewer and Ms Cathy Harper for their helpful comments and advice.

Related webinar: Governance or social resilience: Learning from Southeast Asia’s experience with COVID-19.

Image: People on the streets of Melbourne, Australia, July 2020. Credit: Gordon Best/Shutterstock.