In March 2022, more than two years after the first outbreak of COVID-19 in December 2019, strict quarantine and other public health restrictions on movement were introduced in Shanghai again (and since in other places in China) because of an outbreak of the virus and to maintain the current national policy of ‘zero-COVID’.

As the restrictions in Shanghai were eased in June, a spokeswoman for the Shanghai government Yin Xin, stated: ‘Everyone has sacrificed a lot. This day has been hard-won, and we must cherish and protect it and wish we can welcome back the Shanghai we are familiar with and missed.’

Sacrifice is one of the central concepts in the collectivist and nationalistic discourse and it has been necessary to maintain China’s on-going ‘zero-COVID’ policy. Compared with the general public, grassroots personnel such as social workers have sacrificed more than most.

In China’s governance system, grassroots personnel are the backbone that supports the operation of society. During public health emergencies like COVID-19, their role has become even more important. Grassroots personnel have the responsibility to implement COVID-19 government policy while still trying to serve the interests of the communities in which they work.

From the top-down dimension, local governments in Chinese cities are required to promptly publish strict policies to respond to public emergencies as well as maintain social stability and economic development. Correspondingly, from the bottom-up dimension, the implementation and promotion of these policies relies on grassroots personnel. They need to serve the community while still being agents of the party and state. Thus, grassroots personnel have faced unprecedented responsibilities and challenges during the pandemic.

Social workers are one of the representative sub-groups of grassroots personnel. This article takes research data related to Chinese social workers during COVID-19 to examine their roles and challenges when maintaining current prevention and control policies while also fulfilling their duties to individuals and community.

Grassroots personnel are service providers without rest

Social workers in China are key to implementing pandemic-related public health policy and provide professional services to the public. This includes, but is not limited to, measuring the temperature of individuals and performing other health tests, providing psychological services and treatment, building social support networks and assessing other needs of the community, particularly vulnerable individuals. According to a survey of Chinese social workers in 2020, 83.8 percent have had the daily task of measuring temperatures, 58.1 percent have helped residents acquire necessities such as food and medicine, 91.06 percent were required to distribute materials to residents every day, and 72.07 percent have conducted psychological consultations and treatment. Social workers have also liaised with other community workers, volunteers, and medical professionals to fulfil the needs of residents. If there is an outbreak of the virus, grassroots personnel in that area are expected to be on standby day and night without rest. Screening the close contacts of confirmed cases, organising large-scale infection testing, monitoring those in home quarantine, and all the other daily services related to the pandemic are within their scope of responsibility.

Physically and psychologically social workers and other grassroots personnel have been facing extreme physical and mental fatigue. A serious problem is the lack of reward and material benefit from their work. Grassroots personnel in some areas have only been receiving basic wages because performance-related salary has been suspended due to the strain on available funds during the pandemic and many have not been paid for overtime. Their own mental health is also a challenge. Even well-trained social workers need help to mediate their mental pressure in some cases, not to mention the large number of Chinese grassroots personnel who still have not received professional training to help themselves. However, the support for grassroots personnel is not widely available. Due to these challenges, grassroots personnel have become physically and mentally exhausted.

Grassroots personnel as policy implementers facing pressure from governments and communities

Besides their daily work of providing social service, most social workers and other grassroots personnel have the responsibility to fulfil a political role of implementing and publicising government policies. This requirement remains strong, despite the efforts of many trying to restore their sociality in their daily work.

Chinese ideological centralism requires them to maintain the political role in their daily work, especially during the pandemic, and this has made it difficult to balance the individual demands of residents and the administrative instructions from governing authorities. According to the survey in 2020 mentioned above, 98.32 percent of the respondents have helped distribute public health information and political propaganda, 98.88 percent have responsibility to fill in regular government documents and forms to their supervisory departments (such as reports relating to quarantine in the community), 94.97 percent disseminated information about new policies and public health restrictions within the community, and 89.94 percent provided policy consultations, mainly for those who needed home or centralised quarantine and those who needed to travel to other cities but were not familiar with the requirements and restrictions or who generally needed to be informed of updated policies and rules.

With the pandemic and related policies constantly changing, social workers and other grassroots personnel have had to keep abreast of evolving policy to ensure the effectiveness of enforcement. In this process, their political role as policy implementers, coadjutants, and propagandists has become their routine work.

It is highly stressful to become the bridge between citizens and the government. Social workers have been under immense pressure to implement top-down policies relating to ‘zero-COVID’ and the ‘stability’ of society. To avoid being punished for not doing enough, it’s perhaps no surprise that social workers and other grassroots personnel have sometimes implemented government policies too vigorously.

The policy of ‘zero-COVID’ has been ordered to be achieved at all costs, which has left little room for social workers to mediate and negotiate with local communities who are dissatisfied with the level of support and services. As a result, significant tension between residents and grassroots personnel has developed in some communities. Some extreme examples such as preventing cancer patients without negative COVID-19 test results from seeking medical treatment and imposing a one-size-fits-all policy when allocating people to centralised quarantine without considering individual circumstances have caused great controversy. Additionally, the pandemic has resulted in the absence of some regular professional services (such as case work that helps individuals to overcome social and mental problems) which also deepened the estrangement between residents and the grassroots personnel, who have faced complaints, verbal abuse and even violence in some circumstances.

The ‘zero-COVID’ policy has so far been effective in preventing and controlling the pandemic, especially at the beginning. However, the continued enforcement of top-down ‘one size fits all’ public health policy has the potential to create series problems for China as a whole, and its communities and individual citizens. The impact of continuing ‘COVID-zero’ policies on social relationships and the economic impact on the economy and employment may cause individuals to question its rationality.

The stricter the policy the greater the pressure on the grassroots personnel, both top-down and bottom-up. The difficulties of balancing the dual roles of service providers and policy implementers are becoming apparent. As the main actors in both state governance and social governance, Chinese grassroots personnel need better support to help balance the implementation of policies and service provision.

In recent years, China has actively promoted the modernisation of governance capacity and governance systems. Grassroots governance is the most basic arena. Thus, properly situating grassroots personnel between the public and the government is a crucial test for the development of China’s governance capacity.

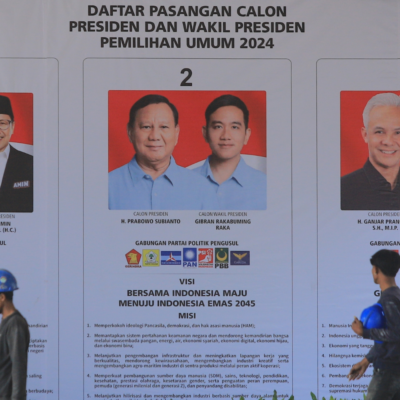

Image: COVID testing in China, July 2022. Credit: QantFoto/Flickr.